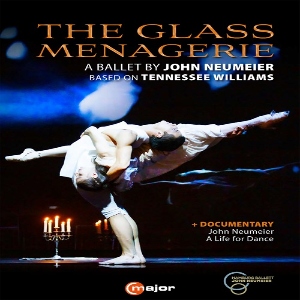

The Glass Menagerie

Ballet by John Neumeier (2019) based on Tennessee Williams

Choreography by John Neumeier

Hamburg Ballet

Hamburg Symphony Orchestra/Luciano Di Martino

rec. 2024, Hamburg State Opera, Hamburg, Germany

John Neumeier – a life for dance

Documentary film by Andreas Morell (2024)

C Major 769008 DVD [2 discs: 184]

If, like me, you have never seen a production of Tennessee Williams’s semi-autobiographical “memory play” The Glass Menagerie (1944), I would strongly advise you to do a little bit of preliminary research before watching choreographer John Neumeier’s 2019 adaptation of the piece for Hamburg Ballet. You certainly don’t need to seek out a staged production or read the full text, but at the very least I’d suggest exploring the piece’s Wikipedia entry.

The booklet that accompanies this new two-DVD set will also prove quite helpful to your research in that it contains a few paragraphs written by Neumeier himself entitled Before watching The glass menagerie. There we discover that, having first seen the play when he was just 17 years old, the choreographer was entranced. “The effect… has never left me…”, he writes, “For years I considered how it could possibly become a ballet, how I might transform [its] extraordinary and moving poetry into meaningful movement.” As it turns out, the experience of working on his 2011 ballet Liliom with the dancer Alina Cojocaru inspired Neumeier to develop The glass menagerie with the intention of casting her as one of the central characters, Laura Rose Wingfield.

Laura Rose is a shy, introverted young girl with a physical disability that keeps her from achieving her full potential. She lives with her mother Amanda and brother Tom, both of whom are equally frustrated in their unfulfilled personal lives. Broadly following the narrative of Tennessee Williams’s original drama, the ballet explores the family members’ interactions both with each other and with Jim O’Connor, a character who, once introduced into their lives, affects each of them in different ways. For Amanda, Jim offers an opportunity to recall her younger days as a desirable young woman. Meanwhile, Tom appears to be dazzled by Jim’s sheer physicality and athleticism (“the love that dare not speak its name” certainly wasn’t doing so back in 1944). In Laura Rose’s case, he is her first “gentleman caller” and thus a knight in shining armour who might offer her a chance to escape her family’s claustrophobic and self-obsessed existence. Ultimately, however, Jim abandons the Wingfields in order to pursue his own life, leaving Amanda, Tom and Laura Rose once more isolated and alone.

Anyone who’s familiar with the play will, however, notice at once that the 21st century ballet introduces some significant changes of emphasis to Tennessee Williams’s original themes. Perhaps the most notable is the shift of the central focus from Amanda to Laura Rose. At the same time, the previously latent homoerotic undertones in the scenes involving Tom and Jim are more explicitly spelled out. Such things might justifiably be regarded as Neumeier simply changing the perspective from which he (and therefore the audience) views the story. He goes somewhat beyond that, however, when he also makes some significant changes that expand and clarify the narrative. Thus, he introduces several lively new scenes set in the world outside the Wingfields’ home. One occurs in a bar, another in the shoe factory where Tom is employed and a third takes place in a typing class where Laura Rose is dipping a hesitant toe into the world of work. Each is a welcome addition that adds colourful detail to the story and variety to the dancing, while providing opportunities for the other members of Hamburg Ballet to demonstrate their considerable skills. Several brand new characters are also introduced. We occasionally, for example, see two personifications of Tom – as both a child and a young adult – on stage simultaneously.

Neumeier also introduces the figure of Tennessee William himself. Sometimes we watch him simply observing the Wingfields’ hothouse lives in a detached manner. At other times, however, he seems to mutate into an older version of Tom who then participates, to varying extents, in the on-stage action, thereby reminding us that The glass menagerie is both semi-autobiographical and a subjective exercise in recalling the past. Another new on-stage character, Betty, is also introduced. When, in the play, Jim tells the Wingfields that he is engaged to another girl and cannot, therefore, court Laura Rose, the theatrical text leaves it unclear whether that is the truth or merely a fabricated excuse. It might be assumed that Neumeier resolves any doubt on the matter when he brings Jim’s fiancée, the aforementioned Betty, briefly on stage before she and Jim leave the distraught Wingfields’ lives for good. However, that might simply be a bit of directorial playfulness or misdirection, for it’s clear throughout the productionthat the action presented on stage isn’t necessarily a depiction of objective reality. Might “Betty” therefore be intended as a figment of the other characters’ imaginations as they listen to Jim’s excuses, rather than a supposedly real person?

Observant readers may have noticed that the word might appeared in each of my last three sentences. That lack of certainty on my part demonstrates, I think, that we viewers would benefit from some extra guidance about how and why, for the specific purposes of the ballet, such story modifications have been introduced. I’m afraid that the booklet is of no use at all on this occasion, for, rather than explaining the revised plot’s idiosyncrasies, its successive analyses of the ballet’s 19 scenes do no more than simply list the music used in each one. While others might choose to argue that a degree of ambiguity forces audiences to think and reach their own conclusions, I can only say that on this occasion and in my own case I would have welcomed a little more elucidation. As it was, I certainly didn’t find that ongoing puzzlement ultimately led to a satisfyingly cathartic resolution.

The designation that Neumeier attaches to his ballet is also surely significant. The words he has chosen don’t tell us that the production is “based on” the play The glass menagerie, or that it is “inspired by” it, or that it “explores themes” from it. Indeed, they don’t actually seek to relate the ballet specifically and primarily to the play at all. Instead, Neumeier simply states that his ballet is “based on Tennessee Williams”. While that presumably confirms that he’s made a deliberate creative decision to emphasise the story’s autobiographical elements, the booklet notes once again let us badly down by failing to offer any further clarification or detail.

As you will note from the review’s heading, the score to The glass menagerie utilises music taken from works by American composers Charles Ives (1874-1954), Philip Glass (b. 1937) and Ned Rorem (1923-2022), all very well performed by the Hamburg Symphony Orchestra under Luciano Di Martino. Various popular music hits are also heard from time to time as the family members listen to a series of 78 rpm discs on their wind-up gramophone. I love you by Paul Whiteman and his Band (1923) pops up no less than three times and is, in the Wingfields’ personal circumstances, a rather ironic soundtrack to say the least. We also get to hear Red Nichols and his Five Pennies in Whispering (1928) and Bob Crosby and his Orchestra playing The world is waiting for the sunrise (1929 – after which the world would, I’m afraid, have a very long wait). All the music, from whichever genre, has been well chosen and works very well with John Neumeier’s choreographic style.

That particular style itself is something that need not worry anyone unfamiliar with modern dance. During his five decades long career as both the Director and an extremely prolific principal choreographer at Hamburg Ballet (1973-2024), John Neumeier tended to concentrate on narrative ballets that allowed him to focus on the area that particularly fascinated him – individual characters’ personalities and motivations. In doing so he developed a choreographic style that, while embracing modernity in all its frequent and sometimes disturbing angularity and spikiness, remained recognisably embedded in the classical ballet tradition and invariably reflected a degree of humanity that was often absent in the work of his more uncompromising contemporaries.

Given Neumeier’s exceptionally long stint in Hamburg, it is hardly surprising that the dancers – every single one of whom would have been hand-picked by him for the company – appear completely at home with his choreographic language. Alina Cojocaru fully justifies his faith in her as she gives an outstandingly moving performance as Laura Rose, effectively conveying the girl’s emotional complexity in both her dancing and her acting. Her colleagues taking the other major roles are, meanwhile, just as good. Alessandro Frola convincingly communicates both Tom’s aspirations and his frustration with his current life, while, in the role of the mother Amanda, Patrizia Friza gives a cleverly balanced performance that generates both pity and more than occasional amusement. Edvin Revazov is impressive in the difficult, semi-detached role of Tennessee Williams. Christopher Evans makes a good fist of the role of Jim, clearly delineating the character’s emotional trajectory from gung-ho happy-go-lucky jock to a man running as fast as he can from the Wingfield family’s personal brand of destructive introspection.

The on-stage sets – all designed by John Neumeier himself, as, indeed, are the costumes and the production’s lighting – are kept relatively simple. Whether we are in the cramped, drab and faded apartment that effectively mirrors the way in which the Wingfields see life itself or the hectic environments of a busily manic factory production line or a fiercely regulated typing class, they effectively convey the appropriate atmosphere. The few props – a large table here, a bar there – are quickly and easily shifted around by the dancers so as to offer some visual variety and to effect necessary changes in the spaces available for dancing.

The well-filmed production is presented in a two-disc set. The complete ballet, 131 minutes, comes on disc 1. Disc 2 offers a documentary film John Neumeier – a life for dance that looks broadly at the choreographer’s life and artistic achievement and makes some interesting and enlightening points. It turns out to be one of the better supporting features that I have come across lately. The picture and sound quality on both discs was absolutely fine. Unfortunately, MusicWeb was not supplied with a copy of the Blu-ray version of the performance – which, I suspect, is the format that will be of more interest to serious collectors – and so I cannot comment on its technical quality.

All in all, this is a very welcome release of an intriguing new ballet. It would be good if any future re-releases were to offer more background information that would answer some of the questions raised by the reworking of the stage play for dance. In the meantime, however, it should be enough to take a good look at that Wikipedia entry or even to seek out a production of the original play. By so doing, you’ll certainly be better prepared for your encounter with John Neumeier’s distinctive new perspective on Tennessee Williams.

Rob Maynard

Cast and production staff

Laura Rose Wingfield – Alina Cojocaru

Tom Wingfield – Alessandro Frola

Amanda Wingfield – Patricia Friza

Tennessee – Edvin Revazov

Jim O’Connor – Christopher Evans

The unicorn – David Rodriguez

Malvolio – Marc Jubete

The children’s nurse – Stacey Denham

Tom Wingfield as a child – Andrej Urban

Laura Rose Wingfield as a child – Lisa Schneider

Betty – Priscilla Tselikova

Amanda’s gentleman callers – Pepijn Gelderman, Lennard Giesenberg, Matias Oberlin, Florian Pohl, Artem Prokopchuk, Torben Seguin and Illia Zakrevskyi

Revue dancers – Olivia Betteridge, Francesca Harvey, Xue Lin, Hayley Page and Priscilla Tselikova

Solo revue dancer – Emilie Mazoń

Typing instructor – Yun-Su Park

Referee – Vladimir Kocić

Other characters: Viktoria Bodahl, Justine Cramer, Francesca Harvey, Greta Jörgens, Xue Lin, Charlotte Larzelere, Alice Mazzasette, Hayley Page, Madeleine Skippen, Ida Stempelmann, Ana Torrequebrada, Priscilla Tselikova, Francesco Cortese, Pipijn Gelderman, Lennard Giesenberg, Nicolas Gläsmann, Louis Haslach, Alfie McPherson, Javier Monreal, Louis Musin, Tibor Perthel, Pablo Polo, Artem Prokopchuk, João Santana, Caspar Sasse, Torben Seguin, Emiliano Torres, Lizhong Wang, Eliot Worrell and Illia Zakrevskyi

Sara Bellini (flute)

Kaan Alicioglu (violin)

Maia Siradze (violin)

Daria Parkhomenko (piano)

Jakob Kuchenbuch (cello)

Set, light and costumes by John Neumeier

Film direction by Myriam Hoyer

Video direction by Kiran West

Technical details

Filmed in High Definition and mastered from an HD source

Picture format: NTSC, 16:9

Sound format, ballet: PCM stereo and DTS 5.1

Sound format, documentary: PCM stereo

Region code: 0 (worldwide)

Subtitles: English, German, Japanese and Korean

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free