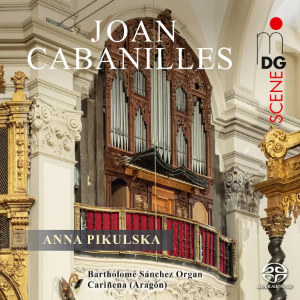

Joan Cabanilles (1644-1712)

Organ Works

Anna Pikulska (organ)

rec. 2024, Iglesia de la Asunción de Nuestra Señora, Cariñena, Aragón, Spain

Reviewed as a download

MDG 906 2367-6 SACD [68]

Spanish music has a special place in the repertoire of organ music. Its peculiar style and the specific timbre of the organs for which it was written make it rather difficult to be performed on organs outside the Iberian peninsula. This has inevitably led to this repertoire being less well-known than that of other countries.

The heyday of Spanish organ music was in the late 17th century, and this was mainly due to Joan Cabanilles. He was born and died in Valencia, where he was unanimously appointed second organist of the Cathedral in 1665. This was remarkable, because the cathedral chapter required an organist to be a priest which Cabanilles was not at the time. It didn’t prevent him from being promoted to first organist in 1666 either; only in 1668 was he ordained a priest. He held this position until his death. His fame is reflected by the wide dissemination of his organ compositions, which were still copied in the mid-18th century. His organ music consists of about 200 pieces and about 1000 versos for the alternatim practice in the liturgy. However, as none of his works were printed during his lifetime and nothing has been left in Cabanilles’ own handwriting, there is considerable insecurity about the authenticity of compositions attributed to him. This is also the reason that his organ works are not often performed and recorded. The disc under review is based on a recent printed edition by Bärenreiter (2022).

Between 2016 and 2019, the British keyboard player Timothy Roberts recorded three discs with pieces by Cabanilles (Toccata). The booklets include some information about the problems a modern interpreter has to deal with. “Internal evidence shows that Cabanilles’ music was originally copied from rather messy sketches in which neither rhythm nor accidentals were precisely indicated; sometimes different possible readings for the same passage were included in the same sketch, while in other instances there apparently existed more than one sketch for the same piece.” (Noel Lee, Volume 2)

Cabanilles wrote his music for his own organ, which was larger than most instruments in his time. Therefore, there are reasons to believe, as Roberts writes in his liner-notes to Volume One, “that some of his cathedral organ music had to be adapted to some extent – whether by the composer himself, or by his pupils and copyists – to make it playable on smaller organs such as those of monastic chapels or parish churches, or even on domestic instruments. Such adaptation would sometimes have included reducing the total range of a work, from the presumed four octaves of the cathedral organ.” Moreover, it seems that some pieces which have come down to us as being intended for split manuals, were originally conceived to be played on two manuals. Roberts believes that this is indeed the case and “that much of his music needs significant re-editing if it is to speak with its true voice.”

Unfortunately the booklet to the present disc does not discuss these matters nor does it specify what the principles of the Bärenreiter edition are. Roberts’ discs include several pieces that he has reconstructed. Whether such pieces are included here is impossible to check, as there seems to be no generally-used numbering of Cabanilles’ works.

In Cabanilles’ oeuvre we find the genres common in Spanish organ music. One of the most popular was that of the tiento, a piece dominated by counterpoint and comparable with the fantasia or ricercare. Tientos sometimes have an additional description, such as partido, which means that the manual is split and one of the hands plays a solo, whereas the other hand delivers an accompaniment. In contrast, tiento lleno refers to the use of the same registration in both halves of the keyboard. The tiento de falsas is comparable to the Italian indication durezze e ligature, which means that they include chromaticism and dissonances. A specific type is the tiento de batalla, in which the clarines are employed. The liturgical pieces in Cabanilles’ oeuvre are entirely ignored here.

A few explanations of the various pieces in the programme may be useful. The opening Tiento lleno de quinto tono is in five sections and in the key of B flat (bequadrado). In the Tiento lleno de segundo tono the addition “por Gesolreut” refers to g and g sharp in the hexachord system. The tiento de falsas de cuarto tono opens with a motif that may refer to the Cross. The Tocata a mano izquierda de quinto tono is in three parts; the lowest, for the left hand (izquierda), plays a solo. The Tiento partido de mano derecha has the solo in the right hand (derecha), which is characterised as a modo de Italia (in the manner of Italy). It is in triple time, similar to a corrente. Both the Passacallas and the Gallardas are based on a repeated motif (ostinato). Lastly, Cabanilles, like other Spanish composers, wrote several pieces with the word Batallas. One may wonder why such pieces were written. They may refer to the battle between the archangel Michael and Satan or to a spiritual battle. It is a shame that the booklet does not comment on specific pieces. I would like to have known, for instance, what the addition “al vuelo” to the Tiento lleno de sexto tono means.

As mentioned above, Cabanilles’ organ was larger than most instruments in his time; many pieces require an organ with two manuals. The organs he knew lacked the reed stops which were part of other Spanish instruments; they were gradually installed in Valencia during Cabanilles’ time. No organ of this type has survived in a condition which allows a recording of Cabanilles’ oeuvre. The organ played here has both two manuals and reed stops. Although this is a fine instrument, the tuning is questionable. “Until the end of the 18th century, many Spanish organs still had meantone temperament, though this was no longer so in Cariñena. Modern tuning, which is pleasant and versatile, was therefore adapted to the existing pipes.” What ‘modern tuning’ exactly means is not explained. The quote indicates that Cabanilles’ own organ very likely was in meantone temperament. It is disappointing that this is ignored in the choice of the organ for this recording. The ‘modern tuning’ may well be the reason that the Tiento de falsas de cuarto tono sounds rather harmless.

Until recently, no modern performing edition of Cabanilles’ keyboard works was available. It is to be expected that the publication by Bärenreiter will result in more performances and recordings of his oeuvre. The present disc is a fine survey of the non-liturgical part of his output, which includes examples of the various genres. The Polish organist Anna Pikulska, who has won prizes in several competitions, is an excellent player, and I certainly have enjoyed her performances, which are stylistically convincing. She uses the possibilities of the organ to good effect in pieces with contrasting sections, such as the Tiento lleno de quinto tono which opens the programme.

However, the tuning of this instrument is a blot on this production, which may not bother every lover of organ music, but will be a matter of concern to those who have more sensitive ears.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

https://bsky.app/profile/musicadeidonum.bsky.social

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Tiento lleno de quinto tono por bequadrado

Tiento lleno de sexto tono (Al vuelo)

Tiento lleno de primer tono sobre ‘In exitu Israel de Aegypto’

Tiento lleno de segundo tono por Gesolreut

Pasacalles de primer tono

Tiento de batalla de quinto tono punto bajo

Tiento lleno de Cuarto tono

Tiento partido de mano derecha de primer tono en tercio a modo de Italia

Tiento de falsas de Cuarto tono

Tocata de mano izquierda de quinto tono

Tiento lleno de sexto tono

Tiento partido de mano izquierda de segundo tono

Gallardas de tercer tono