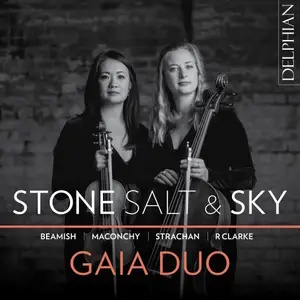

Stone Salt & Sky

Rebecca Clarke (1886-1979)

Grotesque (1918)

Lullaby (1918)

Sally Beamish (b.1956)

Stone, Salt and Sky (2021)

Elizabeth Maconchy (1907-1994)

Duo (Theme and Variations) (1951)

Katrina Lee and Alica Allen

Antibes (2021)

Duncan Strachan (b.1987)

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird (2021)

Gaia Duo

rec. 2022, Haddington, UK

First recordings: Beamish, Lee/Allen, Strachan

Delphian DCD34263 [60]

Duos consisting of a violinist and a cellist are far from common, but when they are as good as the Gaia Duo proves itself to be – Katrina Lee being the violinist and Alice Allen the cellist – on this excellent disc, one wonders why. I hope not only that this Duo flourishes, but also that more duos of violin and cello come into existence.

The Gaia Duo’s programme is innovative and intelligent. They open with two contrasting miniatures by Rebecca Clarke, in line with their ambition to explore the work of composers who get less attention than they deserve. Grotesque and Lullaby both live up to the implications of their titles: Grotesque – only very slightly longer than two and a half minutes – is full of off-centre dance rhythms and abrupt, surprising turns. On the other hand, the slightly longer Lullaby, which plays for 3:16 is, as its title leads one to expect, more soothing.

Two works on this disc were commissioned pieces. Sally Beamish’s Stone, Salt and Sky was commissioned for performance at the St. Magnus Festival, which prompted Beamish to write a set of three short pieces (playing for 4:33, 7:33 and 4:10), each evoking a different aspect of Orkney’s landscape or history. Although born in London, the composer lived in Scotland for some years. The first piece, ‘Processional’, begins with the sound of stamping (marching?) feet, fittingly for a piece in which, according to the composer, “the music suggests outdoor processions and ceremonies throughout Orkney’s history”. However, as Lucy Walker suggests in her excellent booklet essay, there is “perhaps a nod to the rumbustious annual ‘Ba’ Games’ in Kirkwall. In this annual game – like many other long established such games, which often originated in the Middle Ages – two teams, the ‘Uppies’ and the ‘Doonies’, compete to get the ball to their end of the town. The ‘battle’ can surely be heard in ‘Processional’, even if the music is more clearly structured than such a game could ever be. The second movement of Beamish’s suite, ‘Horizon’, evokes images of the surrounding sea and the wide horizons characteristic of the Orkneys. Historic connections with Norway are also hinted at in several echoes of Hardanger fiddle-music. The third movement in the suite ‘Harbour Blues’ is described by Beamish in her notes on Stone, Salt & Sky at her website as “a blues-infused rhythmic dance – maybe even a sea shanty – using chopping techniques, harmonics and pizzicato”. Katrina Lee and Alice Allen seem to relish the ebullience of this movement, with its extensive use of syncopation and a quasi-improvisational quality such as one might encounter in the folk music of the Orkneys. Beamish’s impressive suite was premiered by these performers on 20 May 2021 at the St. Magnus Online Festival.

The other commissioned work on this disc is Antibes, composed by the members of Duo Gaia, which was commissioned by London’s Courtauld Gallery. Its music responds to Manet’s painting of the same title now in that gallery, which can also be seen on the Gallery’s website. Monet visited Antibes in 1888 and was startled by the beauty of the town, creating a goodly number of works during a stay of several months, including this painting in the Courtauld, which captures the Mediterranean light and the sea behind a wind-blown tree on the shore. I suspect that in composing their response to this individual painting, Katrina Lee and Alice Arnold also looked at some of the other works Manet produced during his stay in Antibes. The writing and the playing are hypnotic in Antibes – particularly in the interplay between the two instruments. The subtlety of effect is beautiful and compelling, with the swaying of the violin above the cello producing a kind of aural image of the tree in the Courtauld’s painting, but the work is more than merely mimetic. Its meditative quality captures the intensity of gaze implicit in Monet’s painting, as well as the dialogue between stasis and movement.

I have left until last what I take to be two of the most substantial works on this disc: Elizabeth Maconchy’s Duo (Theme and Variations) and Duncan Strachan’s Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird. Dame Elizabeth Maconchy has increasingly come to be recognised as one of the most important and distinctive British composers of the Twentieth Century. She also made major contributions in her roles as Chair of the Composer’s Guild of Great Britain and President of the Society for the Promotion of New Music. Amongst her own compositions, her cycle of thirteen String Quartets, written between 1932 and 1983, probably stands highest in critical appreciation. Her Duo (Theme and Variations) was writtenfor performance by the violinist Anne McNaughton and her husband, cellist Arnold Ashby. It consists of a brief theme and eight variations thereon. The theme is an original one and is well described in Lucy Walker’s perceptive booklet essay as “a ‘cell’ of three descending quavers, presented first in the cello as falling semitone + tone and then repeated in both cello and violin with variations of the intervallic content”. The work needs to be heard in its entirety to appreciate the subtlety of Machonchy’s contrapuntal skill, though some of the individual variations stand out, worthy of attention as individual musical objects, as it were. Take, for example, the beautiful, upbeat use of pizzicato in Variation III or, by way of contrast, Variation IV, marked ‘Molto moderato, espressivo’, in which the use of double stopping comes close to persuading the listener that he or she is listening to a full String Quartet. In the last variation (no. VIII, marked ‘Allegro molto’) the texture is thickened again, before the original theme re-emerges at the close. This review would be excessively long if anything like justice was done to each of the variations. Suffice it to say that this Duo: (Theme and Variations) is a minor masterpiece of twentieth-century chamber music.

Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird by Duncan Strachan, which closes this disc may not qualify for praise on quite such a scale, yet it is a fascinating piece in its own right. I have to confess that Strachan’s name was previously unknown to me, but I shall remember it from now on. He is a cellist (a member of the Maxwell Quartet) as well as a composer, brought up in the Western Highlands of Scotland, before studying at St. Mary’s School of Music in Edinburgh and reading music at St. Catherine’s College, Oxford. This work is obviously a response to ‘Thirteen Ways of Looking at a Blackbird’ a remarkable poem by the American poet Wallace Stevens (1879-1955). The poem was published in Stevens’ first collection Harmonium in 1923. It is in thirteen numbered short sections, presenting, one might say, thirteen different perspectives or ‘ways of looking’, and raising many different questions about the nature of perception and man’s relationship(s) with the natural world. Any attempt to analyse the poem here would be excessive and finally irrelevant, but it may be useful to observe that it concerns the inevitable subjectivity of how, for example, we see and comprehend the world we occupy. The subjectivity thus implicit in the subject matter of the poem, is also present in how each of us reads it.

Wallace Stevens leaves open the question of where the poem is set, and perhaps a specified location would be largely redundant in so ‘philosophical’ a poem. I quote the first of the poems thirteen short sections:

Among twenty snowy mountains,

The only moving thing

Was the eye of the blackbird.

If one had to offer a guess one might suggest that this refers to a winter scene in the New England where Stevens spent much of his life. By way of contrast, Strachan clearly locates his musical response to the poem in Scotland, doing so in an interesting way. Alongside his music for violin and cello, Strachan incorporates two archive recordings of Scottish folksongs, Belle Stewart’s performance of ‘If I were a blackbird’ and Charlotte Higgins singing ‘What a Voice’, which includes the line “There is a blackbird sits on yon tree”. The modal nature of both these songs seems to be further reflected in the musical language of Strachan’s piece as a whole, as for example in its fourth section which carries the title ‘A man and a woman are one’, the first line of the fourth section of Stevens’ poem:

A man and a woman

Are one.

A man and a woman and a blackbird

Are one.

Stevens’ lines, with their affirmation of unity, are undercut by the contributions of the two recorded songs. The first verse of ‘If I were a blackbird’ goes as follows:

I am a young maiden, my story is sad

For once I was carefree and in love with a lad

He courted me sweetly by night and by day

But now he has left me and gone far away.

The text of ‘What a Voice’ is too long to quote in full, but the following extracts confirm its similarity to ‘If I were a blackbird’:

What a voice, what a voice, what a voice I hear,

It’s like the voice of my Willie dear.

And if I had wings like that swallow high

I would clasp in the arms of my Billy boy.

When my apron it hung low

My true love followed through frost and snow

…

He’s called a strange girlie to his knee

An he’s telt her a tale that he’s once told me.

…

I wish I was a maid again.

But a maid again I will never be[.]

The two recorded songs added to the text of Stevens’ poem by Duncan Strachan are songs of abandoned or betrayed young women, adding a new emotional intensity to Wallace Stevens’ poem. In short, by the use of his own artistic medium of music, Strachan has enriched the meaning of Wallace Stevens’ great poem, in a manner akin to what happens when a great song writer, like Schubert, sets an inferior text. In doing so, this work rounds off perfectly a disc which is consistently intriguing.

Glyn Pursglove

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free