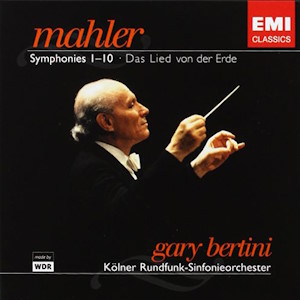

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphonies 1-9, Adagio symphony 10, Das Lied von der Erde

Kölner Rundfunk-Sinfonieorchester/Gary Bertini

rec. 1984-1991, Cologne & Suntory Hall, Tokyo

Essays and texts in English, German & French

EMI 3402382 [11 CDs: 772]

Despite the relative obscurity of its conductor compared with exponents such as Bernstein and Tennstedt, since its issue in 2005 as a tribute following Gary Bertini’s death, this has been touted by connoisseurs as a dark horse among sets of Mahler symphonies. Several of the symphonies had been issued previous to all Bertini’s Mahler recordings gathered into this box set and were very well received. Unfortunately, it is currently out of the catalogue and I have no idea whether Warner Classics intends to re-issue it, hence my assessment of it is presented here as an article rather than a review; only used copies are currently available and they are often expensive – although I recently managed to acquire mine at a bargain price, hence this assessment.

Having read several reviews, I conclude that reactions vary between those who claim this to be in many ways the best of modern accounts – “virtually flawless” – and those who acclaim it as just very good, not because every symphony is individually the best account to be had but because of its overall quality and consistency – but nowhere do I find anything negative. Tim Perry comprehensively reviewed it for MusicWeb in 2007 and he clearly belongs to the first category, declaring, “As a complete cycle of Mahler symphonies, Bertini’s box is second to none.” Either way, it is clearly a collection which deserves the attention of any Mahler aficionado.

My own general impression of Bertini is that he is primarily a non-interventionist conductor who maintains a broad overview, focusing upon structure and coherence and intent upon serving the music without necessarily imprinting his own personality upon it – but let me first enumerate a few little gripes. The most important point is that this is not strictly “complete”, as only the Adagio of the Tenth Symphony is included; like many conductors of his generation, Bertini did not perform Cooke’s reconstruction. Secondly, I have never really seen the case for regarding Das Lied von der Erde as another symphony; while I am happy to have it included here, I would have preferred to have had instead a complete performance of the Tenth. Thirdly – and here I quote an Amazon review with acknowledgements – “in order to cram all the music onto just eleven CDs, the various symphonies are sometimes awkwardly distributed over two discs whereby the chronology is sometimes interrupted.” As TP points out in his review, the distribution of symphonies could have been more conveniently organised without requiring any more CDs. Lastly – and of negligible concern – the spine of the set oddly refers to these recordings as “MONO/STEREO” when they are clearly all digital.

Symphony No. 1

My MusicWeb colleague Lee Denham included this in his comprehensive survey, adjudging it to be “extremely good, if not great”. The playing of the Cologne orchestra is noticeably virtuosic and I love the way Bertini segues from the “Dawn of Creation” introduction into the bucolic jaunt; everything he does is so natural – as Lee says, “fresh and direct”. His tempi are quite swift – indeed, sometimes I think the allegro passages sound a tad rushed but there is a cheerful lightness about this performance which is most appealing. I have heard darker, more menacing interpretations but this all hangs together coherently and the climax of the first movement is exhilarating – if, again, very fast, and that urgency spills over into the opening of the second movement; I know of no other account quite this breathless but Bertini avoids monotony by careful dynamic variation and the Trio could not be suaver or more elegant, contrasting strongly with the rumbustious first theme. The Bruder Martin/Frère Jacques is sly, slinky and ironic, with some daring application of rubato and I thoroughly prize its subversiveness. The lovely tune from the fourth Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen provides a brief respite from the mocking klezmer music and the movement concludes in a hush before the scream which heralds the finale. I have heard more violent openings but it is by far the longest movement and Bertini paces it skilfully; the great climax exactly half way through before the return of the mysterious opening music is splendidly emphatic, as is the final peroration.

The live sound is full and detailed – hence there is the occasional noise even from the Japanese audience – always the most respectful. My reservations about Bertini’s occasional haste notwithstanding, I really enjoy this version but agree with Lee that for all its many, patent virtues there are other performances that are even better.

Symphony No. 2

There is a general consensus that well played though this is, it is – at least in it earlier stages – hampered by a certain restraint or lack of release; this work has to have a grandeur akin to violence. Bertini does the serene interludes beautifully and is always abetted by the smooth playing of his orchestra but at times I could welcome a touch of the lunacy Bernstein demands. Nobody coming to this symphony for the first time via this recording would be disappointed but if you are familiar with Lenny’s wildness or Klemp’s dogged, granitic concentration, you might find this wanting. The marches are characterised by Bertini’s penchant for urgency and of course one can make a case for his relative holding back because he is looking at the whole arc of this massive symphony and keeping something in reserve for its ultimate apotheosis (see below).

The pizzicato passages in the second movement are as enchanting as any I know and the movement depicting St Anthony preaching to the fishes is very engaging – agogic and free but never fragmented, with good timpani thwacks and brassy blasts, conveying some of the savagery I miss elsewhere. Bertini’s speediness is apt here, suggestive of a kind of comical hysteria.

Florence Quivar sings “O Röschen rot” very beautifully and the accompaniments by various solo instruments are all equally graceful and accomplished. The finale goes really well, too, Bertini finding the tension which was slightly lacking in the first movement. The distanced brass are otherworldly; once again, the excellence of the sound engineering comes to the fore and the drum roll announcing the rising of the dead is tremendous. The chorus and the two soloists are impressive – especially Quivar’s deployment of her lower register – and although Bertini doesn’t at first really take Mahler at his word for the final few minutes: “Etwas bewegter” (moving somewhat faster), he confers a massive dignity upon the climax; it’s one of the most moving I have encountered – and I have not previously heard the organ quite so effectively and prominently highlighted.

In short, I find this to be to be very good, despite my minor and subjective reservations.

Symphony No. 3

This is a grand, noble reading, distinguished by superb orchestral playing; you could be listening to any of the great orchestras of the world. We hear some glorious horns and a riveting trombone solo. The depth and breadth of the sound picture is particularly striking here, too, right from the start; balances are perfect and there is never any need to adjust the volume. Bertini is unhurried in the first movement, which is of course famously protracted but I do not find my attention wandering, so coherent is his direction; it is thoroughly satisfying. Delicacy and transparency are the distinguishing features of “What the Flowers in the Meadow Tell Me” but Bertini then creates a welcome contrast by allowing a much more raucous, aggressive manner to pervade the third movement before the dreamy post horn solo – which is beautifully played although I would have liked it further distanced. Gwendolyn Killebrew sings “O Mensch!” richly, if necessarily sedately, given Bertini’s slow beat, but the concentration is palpable. The boys’ and women’s choirs are delightful in the brief, perfectly paced fifth movement. The finale breathes a bitter-sweet serenity; Bertini takes the risk of expanding the duration to 26 minutes, one of the longest on record – and it works. Particularly prominent flutes lend a heart-piercing purity to its melody and the great central climax half way through is searing, the brass and cellos cutting through the texture so dramatically. The sonority of the Kölner Rundfunk here is astonishing. There follows one of the longest gradual slipping of “the surly bonds of Earth” in the symphonic canon, beautifully gauged and executed.

For me, this is perhaps the most rewarding reading in what is in any case a highly successful cycle.

Symphony No. 4

I have a special affection for the Fourth Symphony as Horenstein’s recording on CfP was my route into loving Mahler many years ago – but it is a bit of a wrench if you go straight from the finale on track 1 of CD4 to the opening of the Fourth, especially as it recorded at a higher volume and a quick adjustment is required.

This is music which wholly suits Bertini’s direct, unaffected manner. Mahler is a “singing” symphonist and he brings out that lyricism here, for example, in the soaring violins towards the end of the first movement and the long line of the “Ruhevoll” melody in the Adagio. In his notes, Kyo Mitsutoshi uses the term “Mediterranean” to describe it and that certainly fits this, the most insouciant of his symphonies. Bertini does sunny good humour so well but without neglecting Maher’s darker, more ambivalent moods – for instance, he also brings out the grim, discordant touches from the fiddler in the second movement waltz. The emotional core of this symphony is surely that third movement with its exquisite, mediative variations; Bertini does everything right here and also succeeds in capturing triumphantly the sheer elation of that magnificent – and surprising – coda.

The vibrant, silvery-voiced Lucia Popp is the soprano soloist in the superficially naïve finale. Some might find Bertini’s tempo a bit rushed in the pounding passages here, when she sounds very slightly harried, but the slow sections are lovely and she maintains an imperturbably steady legato. That very mild reservation concerning the fast speed of the last movement notwithstanding, this is another great success in the series.

Symphony No. 5

In my review of Bertini’s live 1981 recording of this symphony with the Stuttgart SWR, I remarked that I found it to be “A pacier, more refined Mahler Fifth, beautifully balanced but rather too restrained in parts.” Regardless of any changes in Bertini’s interpretative stance – and there are some – it is first immediately apparent that the recorded sound here in this set is superior, despite the excellence of that live account. The other main change is that the Scherzo here is considerably slower by a minute and a half; the other movements remain swift.

There seems to me to be more tension and propulsion about the first movement here – and more weight to the lower, darker instruments. That impression is enhanced by the depth of sound enabled by the engineering. The Cologne brass is especially impressive – and they have a lot to do in this symphony. I would still like a little more wildness in the opening of the second movement but it is better and momentum is sustained throughout. The build-up to the climax twelve and half minutes in is masterful. I remarked of the Scherzo in the Stuttgart performance that I found my attention occasionally wandering, especially as it is the longest of all the symphonies with the exception of the Third; not so here, as his delivery is jollier and more engaging, and brings out the macabre humour more effectively. The famous Adagietto is conventionally paced at ten minutes, without schmaltz but deeply felt and affectionately phrased with – yet again – wonderful sonority, especially from the strings. The finale sparkles with good humour and optimism and Bertini’s control over the interlacing and overlapping contrapuntal themes is adroit, leading to an electrifying conclusion of Brahmsian grandeur.

This is most definitely another highpoint.

Symphony No. 6

Some previous reviews have found the pace Bertini adopts for the opening march too brisk and his emphatic leaning on the beat“ clunky”. It is brisk, certainly, but the soaring “Alma theme” is delivered tenderly enough and I think the contrast between the martial and amatory moods works. Bertini’s way with this music is more detached and objective and I’m not sure that he manages the transition to the pastoral “cowbell” section as mesmerisingly as some; it needs a bit more space, but once the passage is underway it is raptly played. Bertini is always concerned to bring out detail and the brilliance of Mahler’s orchestration is highlighted by his ensuring that the celesta and instruments in the percussion bank such as the rute, cowbells, tam-tam, glockenspiel and xylophone may be properly heard. The Scherzo comes before the Andante as per Mahler’s original intention before he havered. I prefer the movements in that order and they are flawlessly played here; Bertini’s refined, sensitive manner is perfectly suited to the delicacy of the latter and the tranquil ending is ideal.

Bertini adheres to Mahler’s subsequent decision in rehearsal to reduce the three hammer-stroke “blows of fate” in the finale to two. This is a terse, tight account, more neurotic than much of Bertini’s clear-eyed interpretations – as befits this most mercurial and volatile of Mahler’s symphonies and the struggle is palpable. This may be a long movement but Bertini’s grip on its structure is firm and it all hangs together without longueurs. There are interludes that require lighter, brighter flashes of orchestral colouring, keeping the music fresh and vital, such that the hammer-blows come as a shock, then the transition into desperate resistance, culminating in the minor key coda and the final crashing chord like a door slamming shut, seems wholly inexorable.

Symphony No. 7

I always think of the Seventh as the favourite of Mahler connoisseurs; it is not mine as much as I enjoy it. It is Mahler’s strangest, most eccentric symphony, full of quirky little details and peculiar shifts, so perhaps Bertini’s detachment and objectivity are well suited to serving the score favourably, trusting in the composer. It is perhaps surprising that Solti’s glittering 1971 recording has long been a favourite for many; it is not devoid of subtlety despite its velocity but in his comprehensive survey, Lee Denham recommends other accounts over it. Bertini is not among his very top choices but gains a very respectable write-up, beating many bigger names: “When all is said and done if this was the only recording of Mahler’s Seventh Symphony in your collection, you would not be missing much.”

This is recorded at higher volume than most of the accompanying symphonies, so twiddle down – but the sound is superb. Inherent in the music itself, is a kind of agonised persistence through the most remarkable and even perplexing sequence of chordal and harmonic progressions and developments and to my ears Bertini and his orchestra encompass its demands heroically. The soaring lyricism of the central section of the first movement is skilfully juxtaposed against the dark menace of the principal theme. The two Nachtmusik movements either side of the middle “Shadow Music” movement are paradoxically mysterious and consolatory partly because the orchestral sound is so reassuring and all-enveloping and also because Bertini understands and captures the congenial mood of this music, securing an appropriate response from his players. The horn calls are comforting, the col legno pattering suggests the scampering of small creatures in the undergrowth and the listener is shrouded in the warm breath of a summer night rather than menaced. There is some grotesquerie but no danger – that comes in the Scherzo, which is allied in form to the “Des Antonius von Padua Fischpredigt” of the Resurrection Symphony, but more threatening. The subtly spotlit contributions of the mandolin and guitar in the second Nachtmusik and the conclusion are magical. The boisterous, rollicking finale dispels any mist; Bertini delivers it as an ingenuous celebration of life and its pleasures – in direct contrast to the conclusion of the preceding, so-called “Tragic” symphony – dancing its way towards, sometimes jubilantly parodying, but never mocking, tunes from – as I hear it – the Janissary music of Mozart’s Die Entführung aus dem Serail and Wagner’s Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, which are similarly good-humoured creations.

This is another complete success in the set.

Symphony No. 8

A number of reviewers, including Lee Denham, have singled this out as the pick of the crop in this set; indeed, Lee says, “I would happily buy the whole box just for his electrifying account of the Eighth.”

I care about conducting, orchestral playing and sound engineering but freely admit that for me in this work the priority is the singing. In any case, we already know the calibre of the conductor, orchestra, most of the massed chorus, contralto Florence Quivar and the sound engineering from previous recordings in this set; add to that prior knowledge the testimony of other reviewers and the certainty that the presence of Julia Varady in her prime as the lead soprano will be a huge asset, and even before listening I had every hope that that this live performance would be a winner – and so it proved.

Varady is stunning, as she is for Tennstedt in his LPO Live recording, and she is part of a distinguished team of famous names including Canadian Heldentenor Paul Frey and that most versatile of baritones, Alan Titus as an impressive Pater Ecstaticus. Bertini does much more than the bare minimum of “directing traffic” in this hugely complex and challenging work; he infuses all the performers with enormous energy and the balance between orchestra and singers is better than on almost any other recording I know. The conclusion to Part I is breathtakingly thrilling. Is the performance as a whole better than Solti, Bernstein, Sinopoli, Tennstedt (twice: the studio recording on EMI and on LPO Live) or Abbado? Possibly not, but certainly their equal and if Bertini’s special attention to detail appeals, that will be a clincher – likewise, the sound is possibly the best of all and if like me you have a special attachment to Varady in this work, I can confidently assert that she is every bit as good here as she is for Tennstedt and partnered with an even more impressive team of singers.

The long orchestral introduction to Part II is remarkably phrased, sculpted and varied; the acoustics of the Suntory Hall lend it enormous dynamic scope and once again I am reminded that under the baton of other conductors I have found it rather long and prosaic – but not here; it is hauntingly atmospheric, helped by the vividness of touches like the soft cymbal clashes. The chorus and soloists are ethereal with the exception of the one comparative weakness here: Siegfried Vogel’s rather bland, under-powered Pater Profundus; we need a real, old school bass of the Hans Sotin or Martti Talvela type – but he’ll do. The trio for the three female voices is especially lovely; Marianne Haggander and Maria Venuti match Varady for beauty in their solos. The final “Chorus mysticus” provides a transcendent conclusion: first, Varady’s pure soprano soars aloft, then the massed choirs and orchestra tutti with thunderous tam-tam lift the roof. What a great performance.

Symphony No. 9

I have heard three truly great live performances of this symphony over the last year or so: Alpesh Chauhan conducting the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra at the Big Bruckner Weekend in Gateshead; Herbert Blomstedt with the Philharmonia in the Royal Festival Hall and just recently Kazuki Yamada with the CBSO in Birmingham. As such, I have been spoiled for live accounts and wondered whether yet another could fully engage me. However, the tranquil assurance of the opening and the splendour of the orchestral sound quickly drew me into that strangely ambiguous Mahlerian soundworld whereby a meretricious surface calm is constantly besieged by doubts and terrors. Beauty of sound dominates this performance, almost Karajan-style, so some might prefer something “uglier”, evincing more overt Weltschmerz; this is more grand and imposing than biting, although the conclusion is gently rapturous, contrasting vividly with the “fumbling and coarse” (“täppisch und derb”) second movement. Bertini happily swaps hats and delivers a rollicking, roistering, peasant clodhopper of a movement; no room for complaints about over-refinement here and it’s great fun – positively exuding joy. Sometimes you can just tell that an orchestra is enjoying itself. Likewise, the rondo is a riot until the volte-face in the soaring central section which is wonderfully lyrical and expansive.

The violence and energy of the inner two movements again by contrast make the repose of the daringly slow final movement all the more mesmerising; everything comes together to produce something special. The solo violin is especially fine and the tuning of all those exquisite dissonances a delight.

A couple of quickly suppressed coughs apart, right at the end, there is virtually no hint of this being a live performance apart from the vibrancy of the atmosphere. This is another outstanding performance.

Symphony No. 10 – Adagio

There isn’t much to say about this studio recording of the piercingly poignant Adagio, not because it isn’t as rewarding as anything else in this box set, but because it is in a way the summation and compendium of all the virtues of Bertini’s cycle, artistically, interpretatively and technically. Bertini invests the music with a wholly natural ebb and flow, the Cologne orchestra’s playing is luminous and the sound is once again ideally balanced. It may not have the emotional rawness of Bernstein’s account; rather, Bertini offers a crumb of comfort in his expression of a dignified resolve following the devastating despair and dissolution of the nine-note chord. He allows little shafts of sunlight to penetrate the gloom, such as that twenty-three minutes in and in the coda. It is subtle, yes – but never pale. After all, this movement was devised to open the Tenth Symphony, not serve as a valedictory finale.

Das Lied von der Erde

Somewhat tacked on, in my view, and as such superfluous to the symphonic cycle, this will nonetheless be an addition welcomed by Bertini’s admirers, especially as he recorded relatively little and the live performance itself is so good.

The drive and energy of the opening in combination with the power and security of Ben Heppner’s tenor make the strongest impression in the opening song. The beauty of tone and assurance of Heppner’s singing are all the more impressive when one remembers that this was a live performance, without re-takes. His German diction, too, is pellucid and he has heft but can lighten his Heldentenor appealingly for his lighter songs such as Der Trunkene im Frühling. He was good in a later recording for Maazel, too, but is in fresher voice here and much better partnered regarding both his conductor and mezzo-soprano soloist, Marjana Lipovšek. She has a fundamentally ordinary, powerful, but slightly edgy voice, and her tone is certainly preferable to the bottled sound of Waltraud Meier, Heppner’s fellow soloist for Maazel, even if her singing is largely devoid of the dusky shades and nuances brought to the music by such as Janet Baker, Christa Ludwig or Jessye Norman. She delivers a straightforward account of her songs, maintaining a steady line and deploying her lower register appropriately, coping well with the faster, higher-lying passages in Von der Schönheit. What I miss in her performance is any sense of transcendence in Der Abschied, well sung though it is.

As ever, Bertini’s care for clarity and balance pervades this account, reminding us that so much of it has a chamber-music-like quality. In many ways, the revelation to me in reviewing this set has not been so much the excellence of his conducting, which I had hoped for and even expected, but the sheer virtuosity of the Cologne orchestra under his direction. Solo after solo reveals the depth of talent in their ranks in that era 1984-1991 and there are many reviews on MWI attesting to its quality. It was renamed as the WDR Sinfonieorchester in the 90s; I have never heard it live but it continues to flourish in concert and in the studio.

The occasional cough obtrudes; the sound is otherwise consistent with the excellence we hear throughout this set.

I refer you to my survey for my favourite recordings. This would be among them if the calibre of the mezzo-soprano – good as she is – matched that of those mentioned above; nonetheless it remains wholly enjoyable.

Conclusion

To sum up, in my estimation, the most successful movements under Bertini’s hands tend to be those which entail “singing and dancing” and the slower, more elegiac episodes, whereas I am not invariably reconciled to his more propulsive tempi not entirely convinced that extracts the maximum drama from the more Angst-laden passages. On the other hand, his gift for proportion, cohesion and lyricism is admirable and the ear is so often beguiled by the sheer beauty – and humanity – in his presentation of this music. As such, I find myself in the second critical camp: the value of this set derives from the “greater than the sum of its parts” principle; it displays an extraordinary consistency of vision and a remarkable quality of execution, even if in the case of several symphonies I could cite individually superior recordings.

Ralph Moore

Details

Symphony No. 1 in D minor

rec. live 21 & 23 November 1991, Suntory Hall, Tokyo

Symphony No. 2 in C minor ‘Resurrection’

Krisztina Laki (soprano), Florence Quivar (mezzo-soprano)

rec. 29 April-4 May 1991, Philharmonie, Köln

Symphony No. 3 in D minor

Gwendolyn Killebrew (contralto)

rec. 25-27 March 1985, Studio Stollberger-Strasse, Köln

Symphony No. 4 in G major

Lucia Popp (soprano)

rec. 30 November & 4 December 1987, Philharmonie, Köln

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor

29 January – 3 February 1990, Philharmonie, Köln

Symphony No. 6 in A minor

rec. 21 September 1984, WDR Studios, Köln

Symphony No. 7 in E minor

rec. 9-15 February 1990, Philharmonie, Köln

Symphony No. 8

Julia Varady (soprano 1), Marianne Haggander (soprano 2), Maria Venuti (soprano 3), Florence Quivar (contralto 1), Ann Howells (contralto 2), Paul Frey (tenor), Alan Titus (baritone), Siegfried Vogel (baritone)

rec. live 12-14 November 1991, Suntory Hall, Tokyo

Symphony No. 9 in D major

rec. live 20 February 1991, Suntory Hall, Tokyo

Symphony No. 10 in F sharp minor: Adagio

rec. 1-3 July 1991, Philharmonie, Köln

Das Lied von der Erde

Marjana Lipovšek (mezzo-soprano), Ben Heppner (tenor)

rec. live 16-17 November 1991, Suntory Hall, Tokyo