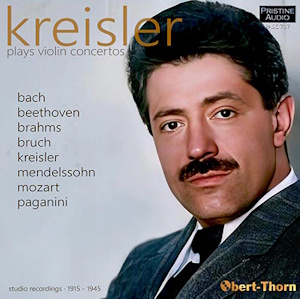

Fritz Kreisler (violin)

Kreisler plays Violin Concertos

rec. 1915-1945

Pristine Audio PASC737 [3 CDs: 208]

This new three-disc set from Pristine covers well-worn territory, offering up all of Fritz Kreisler’s recorded concerto repertoire. Old Kreisler hands will already have all these recordings, although as is now to be expected, Pristine offers them in their typically pristine sound. It is handy to have them all in one place for easy access, rather than spread out across numerous sets.

The first disc kicks off with the 1915 recording of the Bach “Double” Concerto. Kreisler’s partner is Efrem Zimbalist, a violinist whose major contribution to music came in the form of students such as Aaron Rosand, Oscar Shumsky, Joseph Silverstein, and many other superlative players who became the backbone of the post-war American violin world. In a way, the Bach concerto is a potent illustration of the violin “pre-Kreisler” and “post-Kreisler.” Performed with the two soloists and a string quartet, it is absolutely clear from the first note who is playing which part. The first violinist has a small, chaste (some would uncharitably say ‘thin’) tone, and plays without much rhythmic backbone. The vibrato is rather slow and applied sparingly. The second violinist enters, and the tone immediately dwarfs that of the first violinist, traveling through the speakers with a vitality that establishes an almost physical dominance that never relents. The second violinist, of course, is Kreisler: even if he was trying to hide his light under a bushel, the vibrancy of his left hand, his trademark portamenti, and again, the blossoming tone, all serve to identify him. Some moments of questionable intonation in the second movement aside, the performance is a pleasure to listen to, although it’s nobody’s reference version of the piece. Acoustic record lovers take note: the cellist in the quartet is Rosario Bourdon, the arranger and conductor of many “oom-pah-pah” accompaniments for distinguished Victor vocal artists such as Emilio de Gogorza, Louise Homer, and the man himself, Enrico Caruso.

The Mozart Concerto no. 4 comes from 1924, the year before the industry-wide switch to the electrical recording process. Little progress in the way of engineering is audible when compared to the Bach. The orchestra is bigger, but it sounds aggressive whenever it plays above a mezzo-piano, and one is forced to hear the double bass replaced by the tuba, among other re-orchestrations made necessary by the primitive recording process. None of that matters once Kreisler starts playing. The man was born to play Mozart, and it is a crime that Victor or HMV execs didn’t think to ask him to record all three of the major concerti in the electrical era. (His 1939 recording of the 4th concerto with Malcolm Sargent is gorgeous.) His sweet yet vital tone is what my mind conjures up when recalling Mozart’s preferred gentle-toned “butter fiddle.” The ease of his playing is a pleasure to hear in the sixteenth-note runs of the first movement, particularly when he applies terraced dynamics to consecutive phrase passagework. His trills are a delight, being just the right speed for this Goldilocksian-listener (not too fast, not too slow). Yes, his use of portamento is anachronistic, as are his cadenzas (though I believe that Mozart would have been impressed by Kreisler’s double-stops and false harmonics), but who cares? This is Mozart played with joy, simplicity, and an intense songfulness that admirably suits the score.

The 1926 recording of the Mendelssohn Concerto with Leo Blech and his merry band of Berliners is a surprising miss on the part of the violinist. Although his golden tone and noble sense of expression was a natural fit for the music, it is possible that Kreisler, like most violinists, overplayed this piece, and simply was not taking much care with it at this point in his career. (The possibility of over-familiarity is borne out by a quick look at Carnegie Hall’s program database; between 1920 and 1940, at Carnegie Hall alone, Kreisler performed the piece 11 times, four times with orchestra, and seven times with piano as part of seven different recital programs.) Watching the score as he plays, one notices that accents, phrasing, and articulations are ignored, as are a number of Mendelssohn’s dynamic instructions; the violinist breezes through the score in a lovely but imperturbable manner. The inimitable portamenti that charmed in the Mozart seems overwrought, even self-conscious in the Andante. Only the final movement recaptures the Kreisler magic; he chooses a sensible speed but still sounds as if he is having a good time. Every note counts! Blech has some issues with ensemble here, but it does not detract from the main show.

The Beethoven and Brahms recordings with Blech from the same period as the Mendelssohn are well known, and it scarcely seems necessary to rehearse their qualities. To see if the Beethoven is to your taste, skip to the G Minor episode in the first movement development section. If you, like me, are deeply moved by Kreisler’s reading of this episode, then you will likely find other moments to love throughout the performance. If it strikes you as saccharine, skip directly to the Heifetz/Munch recording. In the Brahms, listen to the opening of the second and third movements. The throbbing emotion of Kreisler’s response to the oboe solo in the second movement may be a bit much for some listeners. If this or his measured but crunchy chordal salvos in the finale don’t speak to you, pull up Francescatti/Ormandy or Milstein/Steinberg records. It should be noted that many listeners prefer the re-makes from a decade later with Sir John Barbirolli due to the improved sound quality, better conducting, and tighter ensemble. Kreisler’s playing may be in marginally improved technical fettle in the Blech recordings, but I find myself equally enjoying the Barbirolli versions on any given listen.

Kreisler’s elaboration of the Paganini concerto (specifically, the first movement of op. 6) follows in the footsteps of the once-common Wilhelmj arrangement; one assumes that Kreisler played the Wilhelmj before tackling his own concoction. The latter-day auditor who comes into the listening experience unfamiliar with Kreisler’s arrangement will be confused; the modern propensity for playing Paganini as fast as possible with zero charm or lyricism is turned on its head here. Kreisler’s Paganini prizes song and elegance above pyrotechnics, though the latter is still present, if disguised. The severely truncated yet self-important orchestral introduction sounds like something penned by Johann Strauss Jr., functioning as a curtain raiser to a Viennese comic song rather than a concerto. Kreisler handles Paganini’s passagework with ease, generally playing at a relaxed pace that allows him to play well in tune and with his typical panache. The 61-year-old Kreisler’s double thirds are still in excellent working order, as are his harmonics, chordal batteries, and trills. When he wants to hit the gas (usually in single-note scales), he does so, playing with a zip that more than matches any of our modern wunderkind. Ormandy sticks to Kreisler like glue, proving his usual mastery of the art of orchestral accompaniment.

The alleged concerto by Vivaldi (in reality composed entirely by Kreisler in 1927) was recorded in 1945, the only piece here to be set down after his near-fatal accident in 1941. (According to period newspaper accounts, the violinist was sprinting across Madison Avenue against the light at the intersection of Madison and 57th in Manhattan and was struck by a truck.) Although the Vivaldi does not suffer in the way of intonation like many of his other post-accident recordings, his vibrato has noticeably slowed, and there is a certain slackness to the phrasing never audible in any other performances contained in this set. The composition is pleasant, but not as memorable as his shorter “in the style of” pieces by Pugnani, Couperin, Martini, etc.

The two recordings with piano are rarities; both indicate a special affinity for the works in question, Lalo’s Symphonie Espagnole and the Tchaikovsky Concerto. The complete Lalo was a regular part of his recital repertoire (performed with piano), occupying the second slot after a large-scale sonata along the lines of the Beethoven “Kreutzer.” His performance of the Scherzando movement is witty and relaxed, yet still impressive from a technical standpoint. The Tchaikovsky concerto occupied an interesting place in Kreisler’s repertoire in that he performed the work often with orchestra until the 1930s, at which point he began playing it in his own transcription with piano as a part of his recital programs. The transcription was published in 1940, but to my knowledge it has never been recorded. This 1924 recording of the Canzonetta sticks to the original, with the exception of the brief coda devised by Kreisler to end the movement that originally continues on attacca. Young violinists should study this performance to understand Kreisler’s peculiar rubato, which comes across as both completely natural and pronounced at the same time.

This is a special release that should be on the shelf of all violinists and violin-fanciers, particularly those who have not yet experienced the magic of Kreisler.

Richard Masters

Previous review: Philip Harrison (April 2025)

Availability: Pristine AudioContents

Bach – Concerto in D minor for two violins, BWV 1043

Efrem Zimbalist (violin), String Quartet/Walter B. Rogers

rec. 4 January 1915, Victor Studios, Camden, New Jersey

Mozart – Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major, K.218

Orchestra/Sir Landon Ronald

rec 1-2 December 1924 , HMV Studios, Hayes

Bruch – Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 26

Orchestra/Eugene Goossens

rec. 29-30 December 1924 and 2 January 1925, HMV Studios, Hayes

Tchaikovsky – Violin Concerto in D major Op. 35 : 2nd movement – Canzonetta

Carl Lamson (piano)

rec. 24 January 1924, Victor Studios, Camden, New Jersey

Lalo – Symphonie espagnole in D major, Op. 21 : 2nd movement – Scherzando

Carl Lamson (piano)

rec. 13 February 1925, Victor Studios, New York City

Beethoven – Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

Berlin State Opera Orchestra/Leo Blech

rec. 14-16 December 1926, Singakademie, Berlin

Mendelssohn – Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Berlin State Opera Orchestra/Leo Blech

rec. 9-10 December 1926, Singakademie, Berlin

Brahms – Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77

Berlin State Opera Orchestra/Leo Blech

rec. 21, 23 and 25 November 1927, Singakademie, Berlin

Paganini (arr. Kreisler) – Concerto in One Movement

Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy

rec. 13 December 1936, Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Kreisler – Violin Concerto in C major (in the style of Vivaldi)

Victor String Orchestra/Donald Voorhees

rec. 2 May 1945, Latos Club, New York City