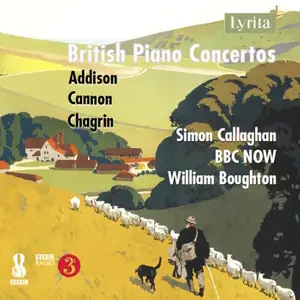

British Piano Concertos

John Addison (1920-1998)

Concertino for piano and orchestra (1958)

Conversation Piece (1958)

Philip Cannon (1929–2016)

Concertino for piano and strings (1951)

Francis Chagrin (1905–1973)

Concerto for pianoforte and orchestra (1943, rev.1969)

Simon Callaghan (piano)

BBC National Orchestra of Wales/William Boughton

rec. 2023, Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, UK

Lyrita SRCD444 [66]

Here we have another volume of Simon Callaghan’s valuable and commendable survey of neglected British piano concertos with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and various conductors. This volume covers three composers who, at least whilst they were composing these pieces, eschewed the prevailing fashion of the period for atonal music – but didn’t necessarily pay the price for doing so.

I was not previously familiar with the music of Philip Cannon or John Addison – the latter not to be confused with Richard Addinsell of Warsaw Concerto fame. Cannon’s artistic credo seems to have been based on Bach’s dictum that “Music exists for the glory of God and the delight of men”. His attractive Concertino, for piano and strings, was written in his early twenties for the Petersfield Festival. There are three movements: a lively, neo-classical Allegro molto that has the pianist’s hands roaming all over the piano at high speed – rarely together – with lots of filigree passagework; a gently lilting Andante tranquillo for which Paul Conway, the note writer, speaks of “a distanced, bygone feel” , “wistful elegance and harmonic piquancy”; finally a busy Presto leggiero that gradually accelerates to an exhilarating climax. Conway draws attention to a “jazzy episode” in the third movement that calls to mind the discordant clashes in the second half of the sixth movement of Warlock’s Capriol Suite, but this similarity was not evident to me. He also finds the second movement reminiscent of Poulenc but, to me, the piece is closer in spirit to the corresponding movements of Shostakovich’s second concerto or Ravel’s G Major concerto. Indeed, given a few outings on Classic FM, this could become similarly popular. In any event, the piece has already achieved no fewer than one thousand performances internationally so, whilst it was new to me, it has obviously already made a considerable mark.

John Addison is represented by two works for piano with full orchestra (rather than just strings). Both pieces could reasonably be described as Concertinos, although only one takes that name. This was commissioned by the Schools’ Music Association for its Festival concert in 1959. Here, Addison seems to have been influenced by Malcolm Arnold, who conducted the first performance of the work. The first movement Allegro moderato correspondingly has much in the way of light-hearted insouciance and opens with discordant brass. The central Andante grazioso is a set of variations on a violin melody at the outset that is interrupted by brass interjections and rises to a central climax before a nonchalant return to a gentle close. The third movement Vivace commences with a call to attention, followed by three contrasting themes and an exploration of their potential. The piece is rather more raucous that Cannon’s work and quite suggestive of Arnold. However, Arnold’s regrettable tendency to cock a snook at the musical establishment, by littering his scores with disruptive, jaunty themes is, mercifully, avoided. The two-section Conversation Piece, written to a BBC commission for the 1958 British Light Music Festival, is rather in the same vein – “wry levity” (with several episodes suggesting intoxication) juxtaposed with “contemplative sincerity”.

Francis Chagrin was, apparently, keen to avoid a “first performances” (only) reputation but his concerto – the most extended piece here – is, arguably, the least successful on the disc. The opening Risoluto movement commences with a trudging theme, on repeated notes, that soon turns out not to be as resolute as initially suggested – giving way rapidly to a lyrical second subject. The movement basically pitches these two subjects against each other until the trenchant final pages. The Lento, molto tranquillo slow movement is elegiac and serene but, for me, slightly outstays its welcome. The main characteristic of the Allegro vivace finale is its “obsessive Bolero-like rhythm”. Those familiar with the music of composers such as Benjamin, Milhaud, Williamson and Jacob will find an eclectic piece that is well put together, often recalling their kinds of music, but without much in the way of memorable tunes.

In Philip Scowcroft’s MWI article on Chagrin and his music, he makes the point that we should probably “not be too surprised that his Piano Concerto and symphonies made relatively little headway, especially on the BBC (despite Chagrin’s connection with the Corporation) in the Glock and post-Glock periods.” Strangely (to my way of thinking) he then says: “But tunes are now coming back and perhaps these works should be dusted down.” Now, with this release, they all have been so here is your chance to make up your own mind.

The recordings are pretty good, despite a tendency to boominess, but the wide dynamic range means that loud percussion and brass sometimes sound, to me, just on the edge of congesting. Somewhat more seriously, I was forced to switch CD players after repeated pressing problems in the first movement of the Chagrin concerto (after about 3’14”) that caused the equivalent of groove jumping, sometimes missing out several seconds of music. Fortunately, the problem did not recur with my second player. The booklet notes are useful and informative. Despite my slight lack of enthusiasm for the Chagrin concerto, all these works are well worth an outing; they are splendid performances.

Bob Stevenson

Previous review: John France (May 2025)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free