Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Il trovatore

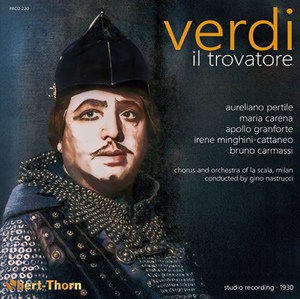

Manrico – Aureliano Pertile (tenor)

Leonora – Maria Carena (soprano)

Conte di Luna – Apollo Granforte (baritone)

Azucena – Irene Minghini-Cattaneo (mezzo-soprano)

Ferrando – Bruno Carmassi (bass)

Chorus and Orchestra of Teatro alla Scala, Milan/Gino Nastrucci*

rec. 24 October-26 November 1930, Conservatorio, Milan, Italy

Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn

Full score and vocal score included for download purchasers

Pristine Audio PACO220 [2 CDs: 115]

In my favourable review of Pristine Audio’s release of the 1928 Aida (review) I noted that Aureliano Pertile’s assumption of Radamès was quite a revelation, both in the quality of his voice and his ability to recreate the emotions of a three-dimensional character, are something that every tenor (and their admirers) should hear. With the recording of Il trovatore coming only two years later, Pertile is less willing to be a communicator and just sings out in a stentorian manner. There is thrilling metallic gleam in his vocal cords but there is nothing especially revelatory about his Manrico. Franco Corelli, whose voice has affinities with Pertile, gives Manrico just as much vocal thrust and he projects a more three dimensional portrait of the character on several recordings (review). Pertile delivers a thrilling “Ah, sì, ben mio” but his musical manners go overboard towards the end of the aria. As I listened to his tendency to sob emphatically I wondered if Richard Tucker had acquired his bad habit of doing that after hearing Pertile sing.

This version of Il trovatore was originally released on a series of fifteen 78 RPM shellac discs which would have been a hefty commitment for the prospective buyer to purchase (and store) during the worldwide economic turndown of the early 1930s. Indeed one can hardly think of a worse time to try and release such a luxury object onto the worldwide market.

Chief among the rediscoveries here is the fabulously incisive Azucena of Irene Minghini-Cattaneo. She was also one of the main assets of the aforementioned Aida. Her Auzcena was caught at the height of her powers, making her one of the finest dramatic mezzos in recorded history. Her ability with words is second to none. She thrusts her words forward in a way that one can only dream of hearing again in modern times. With these two recordings she proves once and for all that the voice should originate by being sung off the words and not the other way around. If only today’s generation of singers would study her example the current standard of performance would improve immeasurably. Try to sample her vividly enunciated “strana pietà’s “, just before Manrico launches into “Mal reggendo”. Her fiery and rather violent, projectile assault on “Deh! rallentate, o barbari” is dramatic singing of the highest achievement, leaving one to exclaim “Brava!” 95 years after this recording was made.

Maria Carena’s Leonora is an example of a type of lyric spinto soprano that has completely vanished in the modern world. Her tone is somewhat reminiscent of Magda Oliviero but without Oliviero’s command of drama or her level of intensity. Carena sings a beautifully floated “D’amor sull’ali rosee” with her shimmering vibrato and interesting use of a glottal chest voice, which is not unlike Monserrat Caballé’s manner of singing during her first years of international notice. People who have become accustomed to the more creamy sound of Leontyne Price in this role might not warm to Carena’s performance, but the warmth and penetration of tone, and her beautifully clear enunciation, are worth hearing for the experience of a lost style of singing.

Apollo Granforte is a Conte di Luna very much in the mode of Leonard Warren. He offers a beautifully even sound which extends across his entire range but gives the listener no special window into what is going on inside di Luna’s psyche. One has to admire the long drawn out phrasing of ”Il balen” which the conductor stretches out so far as to cause Granforte to have to insert breaths within the phrase, and yet the act of doing so doesn’t actually interrupt the baritone’s legato. Astounding when one thinks of it. Even more admirable are the finely produced grace notes which he inserts into the aria, something that I have never encountered on any other recording.

The stygian darkness of the sound coming from Bruno Carmassi’s Ferrando is jaw-dropping, especially in the opening scene; however, he smudges the semiquavers in “Abbietta zingara” as so many basses do(though not Nicola Zaccaria on the first von Karajan recording review).

With the exception of two discs that were conducted by Carlos Sabajon the majority of this set was conducted by the briskly energized baton of Gino Nastrucci. His tempi are admirably defined and never sound unduly rushed. Once or twice (as in “Il balen”) he elongates Verdi’s lines to almost the breaking point; surprisingly nothing goes array, though he really tests the stamina of the singer and the listener. Mark Obert Thorne and Pristine have done their usual laudatory job in creating a clean transfer of this recording to preserve it for future generations. We have cause to be grateful to Pristine’s continued commitment to present ancient recordings in the best possible fashion to be enjoyed anew.

Mike Parr

Availability: Pristine ClassicalPrevious reviews: Göran Forsling (December 2024) ~ Ralph Moore (February 2025)

*Carlo Sabajno was originally credited as conductor but we now know that he conducted only two sides (CD 1 tracks 9-10 and 13-14) and the rest was “ghost-conducted” by his assistant Nastrucci.,