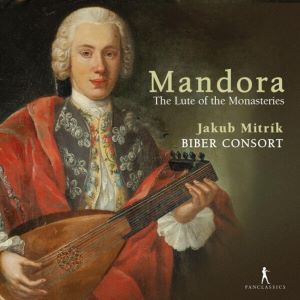

Mandora – The Lute of the Monasteries

Biber Consort/Jakob Mitrík

rec. 2024, Sommerrefektorium, St Florian Monastery, Austria

Reviewed as a download

Pan Classics PC10463 [61]

This is the first time in about forty years of reviewing early music discs that a recording of music for mandora crosses my path. When I saw the title I at first confused it with the mandola, a kind of mandolin. However, the mandora is a member of the lute family.

In New Grove James Tyler mentions other errors regarding the identity of the mandora. Some authors identified it with the mandore, a small treble lute used in France in the 16th and 17th centuries. The mandora was mostly used in the German speaking part of Europe during the 18th century. Some German authors used the term Gallichon or Calichon as alternatives, which caused confusion as it is sometimes identified with the Italian colascione, but that is an entirely different instrument.

The mandora is a bass lute which was often used for the basso continuo, but which was also given melodic parts to play, either solo or in ensemble. Dieter Kirsch, in the liner-notes to the disc under review, states: “[The] mandora emerged as a response to the increasingly complicated lutes of the Baroque period, which had expanded up to 14 courses. Amateur musicians, eager to retain the variable tone of the lute but without its complexities, found satisfaction in the ‘new simplicity’ of the mandora, which was tuned in fourths and a third, featuring five double courses and a single upper course.”

Towards the end of the 18th century the instrument lost its appeal, which was mainly due to the increasing popularity of the guitar, which had single strings and whose construction was simpler. Another reason was that hardly any music for the mandora was available in printed editions, and that mandora parts were notated in tablature, which made them hard to read for amateurs. The shift from mandora to guitar is also documented by the fact that mandoras were converted into guitars.

The research into the mandora and its repertoire has borne fruit. In his article in New Grove, Tayler mentioned 55 sources with music for the instrument, but today over 130 manuscripts are known, which contain more than 5,000 pieces for mandora. It was particularly popular in monasteries, especially those of the Benedictine order. In two monasteries large collections of mandora music have been found: Kremsmünster Abbey and the Prince-Bishop’s court in Eichstätt. Each of them includes more than thirty manuscripts, containing music of different character. In Kremsmünster, the largest part consists of parthias – trios or quartets for mandora and violin(s), transverse flute and bass. In Eichstätt, on the other hand, the repertoire is more varied, and includes vocal music and chamber music in various scorings.

The present disc presents a survey of the repertoire. The programme is based on the collection in Kremsmünster, but for the three vocal items the performers turned to the Eichstätt collection.

In general, the mandora parts in ensemble pieces are not very demanding. That is different with pieces for mandora solo, where the performer has to be able to play in the highest positions. One such piece is included here: the Solo in C is scored for a nine-course mandora. The highest-pitched string (the chanterelle) is tuned to d’ and the lowest course to C, giving the instrument a range from C to c”.

The two anonymous Trios the mandora plays with a melody instrument, either independently or in parallel thirds. In the Trio in A the melody instrument is the violin; in the Trio in D it is the transverse flute. The liner-notes don’t mention whether these instruments are prescribed or left to the choice of the performer.

The equally anonymous Quartet in D, which is comparable with Viennese lute concertos, is simpler: the two melody instruments – transverse flute and violin – double the mandora at the octave in the upper register; the lower part is played in unison or at the octave by the cello. A comparable piece is the Parthia a 4 in A which concludes the programme. Here the mandora takes part in the basso continuo, whereas the two violins play in parallel thirds.

That leaves the three vocal items. Two of them are heard here in arrangements by Joseph Michael Zinck, who was from Eichstätt, and was active as a player of violin and double bass, but has been especially known for his arrangement of vocal music for voice and mandora. The best-known piece is the aria from Mozart’s opera Die Zauberflöte. ‘In diesen heil’gen Hallen’ is originally scored for bass, but here for soprano. It is from a collection dated 1818, and this explains why the guitar is mentioned as an alternative to the mandora.

In the work-list of Franz Xaver Süßmayr in New Grove one won’t find Sultan Wampum oder die Wünsche, a Singspiel based on a libretto by August von Kotzebue. From this piece the aria ‘Juhu, nun will ich leben’ is taken. It is called an “oriental farce with music”, and that explains the character of the aria with quite some onomatopoeias.

The only composer in the programme who is known by name and has left original music for the mandora is Matthias Sigismund Biechteler. That is not surprising, as he was a professional lutenist. From 1706 until his death he was Kapellmeister at Salzburg Cathedral, in which position he succeeded Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber. The Aria de Sancta Scholastica dates from 1716, which makes it the earliest piece in the programme. That year Biechteler moved to a house near the Nonnberg Abbey in Salzburg. “It’s plausible that he wished to introduce himself to his new neighbours with a demonstration of his skills and chose a text in honour of St. Scholastica of Nursia, the sister of St. Benedict, who was especially venerated at Nonnberg”. The solo part is for an alto voice, the instruments are violin, mandora, spinet, organ and violone. Here we get the salterio as substitute for the keyboard instruments and the cello instead of the violone. The mandora part is for a six-course instrument.

As I wrote above, I have never before heard any disc with music for mandora. I can’t imagine the instrument has never been used for recordings. If that is indeed the case, I must have missed them. This disc is an interesting acquaintance, especially as the variety of the programme offers a good survey of what was written for it. As one may have gathered from the description in the previous paragraphs, the music was mostly meant for entertainment. The music performed here certainly is entertaining, even though one should not expect true masterpieces. That doesn’t take anything away from their value; it is to be hoped that more repertoire comes to light and is performed and recorded.

The Biber Consort deserves praise for its efforts to bring the mandora and its repertoire to the attention of the music lover, and it such a fine manner. Jakub Mitrík delivers excellent performances, and his colleagues are the perfect partners. I did not know Antonia Ortner who sings the vocal parts, and also plays the salterio. She has a remarkable voice, with a wide range, covering both the soprano and alto parts, and even moving into the tenor range in Süßmayr.

Lute aficionados certainly should investigate this disc – but anyone who likes to expand his musical horizon should consider this recording, which offers much to enjoy.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Contents

anon

Quartet in D

Matthias Sigismund Biechteler (1668-1743)

Aria de Sancta Scholastica

anon

Trio in A

Solo ex C

Franz Xaver Süßmayr (1766-1803)

Sultan Wampum oder die Wünsche:

Juhe, nun will ich leben (arr Joseph Michael Zinck, 1758-1829)

anon

Trio in D

Wolfgang Amadeus MOZART (1756-1791)

Die Zauberflöte (KV 620):

In diesen heil’gen Hallen (arr Joseph Michael Zinck)

anon

Parthia a 4 in A

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free