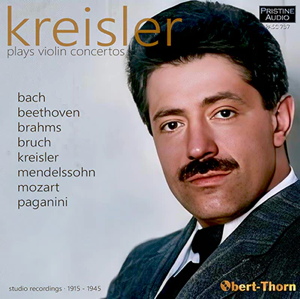

Fritz Kreisler (violin)

Kreisler plays Violin Concertos

rec. 1915-1945

Pristine Audio PASC737 [3 CDs: 208]

Record collectors in the pre-LP days were brought up to hold certain creeds dear. Pablo Casals for Bach, Artur Schnabel in Beethoven, Cortot for Chopin’s Preludes and Ballades, Rubinstein for the Nocturnes and Scherzi; yes, it could get rather complicated! The great Fritz Kreisler was the senior of all these greats and his Beethoven and Brahms concerti in the HMV catalogue were self-recommending. Record aficionado, engineer and music lover Mark Obert-Thorn has worked on the Kreisler concerto records before but never as effectively and with such great results as here in this new set published by Pristine to coincide with the sesquicentennial of the great violinist.

Born in 1875, his huge talent on the violin was spotted early and he was admitted to the Vienna Conservatory at the age of seven. As part of his studies, he took classes in composition with Bruckner. At the age of ten, he won a scholarship to study in Paris where alongside working with some inspiring violinists he took further theoretical study with Delibes. In his teens, he toured America before returning to Austria. As with many child prodigies, he was pulled away from music at times in his late teens, flirting with medicine for a while. By his early twenties, however, Fritz Kreisler was back in the zone and ready to establish himself on the concerto circuit around Europe.

Kreisler played in the greatest concert halls of the world and in 1910 he premiered the Elgar Violin Concerto which had been written for him. At the outbreak of war in Summer 1914, he was commissioned into the army of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and served near Lviv (then Lemberg) in Galicia, fighting the Russians. He was bayoneted and discharged. It had been indeed, quite an eventful career when in 1915, Kreisler relocated to New York (at that stage the US were neutral in the European conflict).

That year in the Victor studios in Camden, New Jersey, he played in the first ever concerto recording, a Bach work, with fellow violinist Efrem Zimbalist. Zimbalist was Kreisler’s junior by 14 years and the husband of the soprano Alma Gluck (an adorable voice). Zimbalist was trained in the school of Leopold Auer (alumni includes Elman, Heifetz and Milstein). The three sides containing Bach’s concerto for two violins and “orchestra” are obviously acoustically recorded. The process involved the musicians crowding around a large horn, the other end of which, in response to sonic vibrations was cut laterally a master disc. The acoustic process, which worked well for singers and reasonably for mid-frequency instruments, was not so great with higher or lower frequencies. The violin’s timbre was always problematic.

The two soloists blend really well together despite their differing temperaments. There is just too much portamento for me especially in the slow movement. They are joined by a string quartet in place of the orchestral accompaniment. Although, not strictly fair in this case, as it is a much later electrical recording (and is uncut), English Columbia recorded in 1937 a version with Hungarians Joseph Szigeti and Carl Flesch (his only major recording). That version made in London with Walter Goehr is my favourite version on 78s. It is available on a Naxos CD transferred by the same Mark Obert-Thorn (review) or in a later Pristine transfer by him. Ward Marston is responsible for the HMV’s of Menuhin and Enescu also on Naxos, a very famous pre-war version of the work. It is good to have this new tidied up version of the Kreisler/Zimbalist Bach Double though, it is an important historic document.

There are more acoustics to come, but they date from a good deal later and the sound is much better. In 1924, at HMV Hayes, Kreisler made Mozart’s Violin Concerto No. 4 in D. The following year the recording industry started recording electrically (microphones). This set of four 12-inch records (HMV DB 815/8) was soon deleted in the mad-dash to get records out in the new format. Copies are thus rare and Pristine have found some really nice sources here. Kreisler is elegance personified. His phrasing is exquisite and the violin is captured remarkably well. Obviously, Kreisler remade the record electrically in 1939, again in London for HMV. That time, they managed to squeeze it onto six sides. In between, Joseph Szigeti (as Kreisler’s main competitor on record, you’ll see his name a few more times in this review) recorded it with Sir Thomas Beecham’s new LPO in 1934 for Columbia. It is a lovely version.

Since Mark Obert-Thorn originally worked on these Kreisler records for Naxos 25 years ago, the technology available to transfer engineers has improved markedly. For Pristine he used a de-clicking software that allowed him to edit the sources within specific frequency bands. This means that extraneous noises and bumps from the studio or the pressing can be removed without touching the musical picture at all. He also used a snazzy module to eliminate swish from those rapidly spinning shellacs. Mark estimates that in the next record of the Bruch concerto he manually removed at least 1600 swishes (21.5 minutes of music x 78 revolutions per minute = 1677). That’s what I call job commitment!

Perhaps the motivation to work so diligently by hand on the Bruch Violin Concerto No. 1 may have been due to the legendary status of that record. It exists in only one known copy in the whole world. The six sides were never approved for release, the metals scrapped and the test copies given by Kreisler to Elgar. They now reside at Yale. I compared this transfer with the Naxos and it is far cleaner now. The tiny groove slip (2:22) seems vanished now too. Kreisler’s lovely warm subtle vibrato and his magical rubato is well caught and the seemingly easeful manner of his bowing is a marvel to hear. Kreisler played the Bruch 2 regularly in concert as well as its more popular cousin. There was never any realistic chance that HMV would have risked the expense of recording that however. In fact, Kreisler never remade the first concerto in the electric era, making this unique version all the more special.

The other complete works on this set are all electrics and Pristine present the three classic concertos by Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Brahms in their first Berlin versions. Connoisseurs of the violinist always did prefer these earlier records to their remakes. For me personally, with these electrically recorded 78s, it is as if a window has been opened and I can now experience the Kreisler sound as it really was with no recession and with all the frequencies audible.

Kreisler’s Beethoven came out on HMV DB 990/5 (11 sides with a Bach solo as filler). It is a generously paced performance. Leo Blech is in no rush at all leading his Berlin Staatsoper forces in an account 45 minutes in length. Kreisler sounds completely relaxed and his playing is effortless. Truly this is the art which conceals art. Listen to his quiet phrasing of the passages beginning at 12:35. His bel canto style seduces one, as if a spell has been cast and any aversion you may have to the odd sweep or slide here and there, soon transfigures into a moment that brings a little twinkle to your eye. Kreisler played this concerto numerous times under the baton of Mahler. I doubt he would have been immune to this magic either.

The cadenzas are Kreisler’s own and listeners will be familiar with them even if you weren’t aware of their authorship (we even get the little one at the end of the slow movement). His rendition of the first of them in this record is immense and must be heard, and what about those trills? The larghetto is pure Viennese class; a sublime, beautifully shaped song of tenderness. You wouldn’t get away with the portamento these days but we can forgive him with playing of this quality. The old Penguin Guide praised its “rapt, Elysian quality”. The finale is all you would expect it to be.

This recording, like the Mendelssohn that follows it, is nearly 99 years old now. Allowances do need to be made; there is some overloading, especially in tutti passages and the bass booms at times. In so many places however, one more often is left marvelling at how well these old records come over in these remasterings. Kreisler’s HMV remake of 1936 was made with the LPO and Barbirolli (review). The sound is undoubtedly finer and Sir John was always extremely proud of it. I do love it and will not give away my preference for now. The 1926 Berlin version has for sure, never sounded better than here in this new set. In 1932 Szigeti’s rival version on Columbia LX 174/8 was recorded neatly onto 10 sides. Bruno Walter collaborated on that one with a pick-up London orchestra (review).

The Mendelssohn concerto came out on HMV DB 991/1000 (7 sides with May Breezes as a little bonus). Throughout this work I was stuck by the softness of Kreisler’s tone. He always kept his bow hair incredibly tight and some say he only used three-quarters of the bow length, keeping it in constant motion and avoiding undue pressure. His fingertips too were said to be like soft pads. He certainly sustains a beautiful line in this work, which evidently meant so much to him. It is a well-considered reading in the romantic tradition with a wonderful finale. Like the Beethoven and Brahms, he remade it for HMV as technology improved (Elgar would have done the same with some of his early electricals I am sure, had he lived). The sound is possibly even better in this work than in the Beethoven, woodwind cuts through more and the surface noise is almost nothing. Pristine have done a sterling job. Szigeti’s version was made with the LPO and Beecham in 1933. You really need that version as well.

Nearly a year later, Kreisler was back with Blech and the Staatsoper musicians to lay down the Brahms Violin Concerto. This was released by HMV on 5 records (DB 1120/4, 9 sides with a Schumann Romance filler). Blech’s orchestra have a bit more fire in their belly than in the previous year’s sessions. The sound however is not as fine as in the Mendelssohn, the grooves sound a little less clean to me. You may hear this particularly in the cadenza. The reading from Kreisler is predictably magnificent. He actually played chamber music with Brahms so we are hearing real authenticity here. The playing is relaxed yet what nobility there is. The rhapsodic beauty of Brahms’ writing after the first movement cadenza, before the coda, is just to die for.

The Berlin Staatsoper had a very fine principal oboe in the late 1920s (but read on for more on that). Kreisler follows his solo in the adagio with violin playing that exemplifies how his style was so revolutionary to contemporaries. Every phrase glows with a soft vibrato that came from his left hand constantly moving and responding to the music. Casals played his cello in this way too. Nowadays, music colleges teach this as standard but it was novel at the time. Kreisler is exquisite in the slow movement and sparkles in the finale.

In the case of the Brahms, I will declare a preference for the later performance with Barbirolli (1936). Much more contemporaneous with this Berlin version though was Szigeti’s on Columbia. As a boy of Lancashire and a lifelong Hallé man, I cannot neglect the chance to promote it. Sir Hamilton Harty recorded this with the great Szigeti in the Free Trade Hall in 1928. It is for me sui generis for this work. The adagio features oboist Alec Whittaker (a legendary player and man; he even got one over on Toscanini once when he visited the BBC SO in the 30s). You-know-who transferred it for Naxos in 2002 and later for Pristine (review). The original 5 shellac set is one of my prized possessions.

Pristine include two later concerto recordings made in America for Victor. In 1936 in Philadelphia with Eugene Ormandy, Kreisler recorded a Paganini set based on his first concerto with all the reworkings done by Kreisler himself. The sound is tremendous with real concert hall ambience. From 1945 we hear a little concerto composed by Kreisler himself in the style of Vivaldi. The violinist had been involved in a serious car accident a few years earlier and was still wobbly. I cannot hear any deterioration in his technique but keener ears might.

The 3 CD set also includes a couple of tiny, might-have-been morsels I have never heard before. They are both acoustics and will please completists. Perhaps Mark Obert-Thorn might be persuaded to return to those remade electrics of Kreisler for Pristine one day. Don’t forget as well that Fritz Kreisler made records of all the Beethoven sonatas for a society issue in the mid-30s (review). For now, I am mightily glad to have had this opportunity to hear the immortal artist in his prime in these stunning new transfers. You should try and do likewise.

Philip Harrison

Availability: Pristine Classical

Contents

Bach – Concerto in D minor for two violins, BWV 1043

Efrem Zimbalist (violin), String Quartet/Walter B. Rogers

rec. 4 January 1915, Victor Studios, Camden, New Jersey

Mozart – Violin Concerto No. 4 in D major, K.218

Orchestra/Sir Landon Ronald

rec 1-2 December 1924 , HMV Studios, Hayes

Bruch – Violin Concerto No. 1 in G minor, Op. 26

Orchestra/Eugene Goossens

rec. 29-30 December 1924 and 2 January 1925, HMV Studios, Hayes

Tchaikovsky – Violin Concerto in D major Op. 35 : 2nd movement – Canzonetta

Carl Lamson (piano)

rec. 24 January 1924, Victor Studios, Camden, New Jersey

Lalo – Symphonie espagnole in D major, Op. 21 : 2nd movement – Scherzando

Carl Lamson (piano)

rec. 13 February 1925, Victor Studios, New York City

Beethoven – Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61

Berlin State Opera Orchestra/Leo Blech

rec. 14-16 December 1926, Singakademie, Berlin

Mendelssohn – Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

Berlin State Opera Orchestra/Leo Blech

rec. 9-10 December 1926, Singakademie, Berlin

Brahms – Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77

Berlin State Opera Orchestra/Leo Blech

rec. 21, 23 and 25 November 1927, Singakademie, Berlin

Paganini (arr. Kreisler) – Concerto in One Movement

Philadelphia Orchestra/Eugene Ormandy

rec. 13 December 1936, Academy of Music, Philadelphia

Kreisler – Violin Concerto in C major (in the style of Vivaldi)

Victor String Orchestra/Donald Voorhees

rec. 2 May 1945, Latos Club, New York City