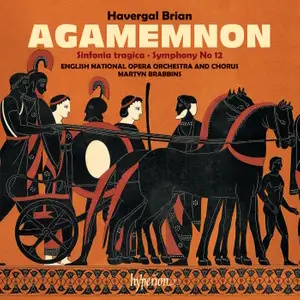

Havergal Brian (1876-1972)

Symphony No.6 ‘Sinfonia tragica’ (1948)

Symphony No.12 (1957)

Agamemnon (1957)

Eleanor Dennis (soprano) – Clytemnestra

Stephanie Wake-Edwards (mezzo-soprano) – Cassandra

John Findon (tenor) – Agamemnon

Robert Murray (tenor) – Watchman

Clive Bayley (bass) – Herald/Old Man

English National Opera Orchestra and Chorus/Martyn Brabbins

rec. 2023, St Jude-on-the-Hill, Hampstead Garden Suburb, London

Libretto included

Hyperion CDA68464 [67]

The year after he had completed Faust Havergal Brian turned to Aeschylus’ Agamemnon, which proved to be his final opera. Its composition, and that of Symphony No.12, was completed within a four-month period and Brian envisaged the symphony as a prelude to the opera. They don’t share any musical material but they do share an oppressive austerity which makes this recording of them both, prefaced by the Sixth Symphony, an especially compelling one.

Given that, a few words about the symphonies might be helpful before we get to Agamemnon. Symphony No.6 ‘Sinfonia tragica’ was completed in 1948. Intended as an orchestral prelude to Synge’s play Deidre of the Sorrows, which Brian never set, it was recast it as a one-movement symphony in three well-defined sections. A standard orchestra is used though one that includes three side drums, and the music is concise and strongly characterised. Sibelius is a distinct presence. The opening is flickering, scurrying and terse whilst the central section, which opens with the cor anglais, sees lyricism battling with martial elements. As the slow movement evolves into a Lento solenne, it possesses an almost Elgarian character and Brian’s serenity here is rather unusual, untroubled by turbulence and avoiding those high wind/low brass conjunctions that are so much a fingerprint of his compositional processes. The finale, however, is launched with vehemence and tumult which proves well-sustained and colourful. A moment of reverie for the winds is immediately undercut by the brass and percussion, and whilst the cor anglais seems to prefigure an emergent pageant funeral march, it’s abruptly cut off by the tam-tam. In Brian, as ever, lyricism is fugitive, the forces of militancy ranged fatally against it.

If you know Brain’s discography you’ll be aware that Myer Fredman made a splendid recording of this Symphony with the LPO on Lyrita back in 1973 which is coupled on CD with Symphony No.16 and Arnold Cooke’s Symphony No.3 conducted by Nicholas Braithwaite. As with Faust this latest disc is performed by the Orchestra of English National Opera under Martyn Brabbins and they are, if anything, even more terse than the LPO and Fredman and equally expressive.

As for Symphony No.12 this recording is significantly quicker than the rival Czecho-Slovak Radio Symphony under Adrian Leaper on Marco Polo, later reissued on Naxos as by the Slovak Radio Symphony, who take 11 minutes to Brabbins’ 9:44. Again, this is one of Brian’s single-movement structures but one that is extraordinarily compressed, a four-in-one symphony that remains pessimistic and bleakly funereal. The opening gestures of the Adagio are soon dispersed by troubled writing and the succeeding funeral march’s grandeur is channelled into an almost obsessive drive. At less than two minutes there isn’t much time for lyricism in the third section though there is some but its uneasiness is amplified by the terse, asymmetric final panel, pummelling in places and again cut short at the end, this time by a soft gong.

If you’ve survived this, then you’re ready for Agamemnon, a tragedy in one act lasting, here, 38 minutes. It employs the 1850 translation by John Stuart Blackie which Brian abridged but also amplified with some of his own lines in choral passages. If, as John Pickard suggests in his authoritative notes, the florid Victorian nature of Blackie’s verse is at odds with the terseness of Brian’s setting, then at least it drew from him some imaginative, if brittle, music. I would say, though, that for all the formal ceremony of the verse, much is not of any direct use, given Brian’s cussed ability to write a vocal line seemingly independent of the orchestral accompaniment.

Such is strongly the case in the opening declamatory scene where the Watchman introduces the return of Agamenon. In a rapidly moving tableau, the Herald then declaims his speech unaccompanied until brass fanfares eventually buttress his words. The chorus remains the defining agent of expressive intensity in the opera. It’s the chorus that brings explicit drama as well as blistering vehemence, and the chorus’ welcome to Agamemnon, reflecting the bloody tale of the Herald, becomes increasingly torrid, perhaps even to the extent of destabilising the welcome and serving to prefigure his death to come. As ever here, the orchestra offers a maelstrom of sonic effects and intensities ready to overwhelm the singers. However, the chorus’ initial wide-ranging presence gradually narrows to terse interjections as the action descends to murder.

Agamenon’s long first speech is verbose and is accompanied by a powerful orchestral palette that only someone with the stamina and clarion diction of John Findon could overcome. His murder, which happens off stage, cannot but help seem bathetic and his lines ‘O I am struck! Struck with a mortal blow!’ sounds less than theatrically convincing. Clytemnestra’s welcome, by comparison, has a very ungrateful vocal line and it’s not always easy to understand what Eleanor Dennis is singing, not least because of the awkwardness and rather arhythmic vocal stresses which, I assume, are meant to suggest her malign purpose. Here, at least, Brian’s orchestration is more ‘cinematic’. Her admission of murder is, in part, accompanied by shadowing winds that sound oddly witty. These two scenes for the central characters remind us that Brian wanted Wagnerian-sized voices or at the very least Strauss-sized ones – I suppose Salome is the obvious example. Cassandra is sung by mezzo Stephanie Wake-Edwards, and her role is a parlando-recitative one, well taken. The Watchman is tenor Robert Murray and the Herald, doubling the Old Man, a kind of Vox populi role, is taken by adamantine Clive Bayley.

Whether you consider Agamemnon an opera or a tableau or something Static-Attic, it frequently functions by disjunctions of tone. The ‘heroic’ music of the final scene is constantly interrupted, and Clytemnestra’s words are undercut by the percussion and brass, sure means by which Brian ensures the troubling nature of the work is understood. Predictably, but tellingly, Cassandra has the most serious and focused music, and she is not destabilised by the orchestration, going to her death unmocked.

I don’t think Agamemnon is the work to convert Brian atheists. Its functional austerity offers little in the way of lyric possibilities. Its vocal lines are largely ungrateful. But it does offer a compact, sealed world that compels as much as it may repel. The Twelfth Symphony is the perfect prelude and the Sixth is a near-masterpiece. This splendid production comes with full notes and libretto. The orchestra, chorus and recording are superb, and Brabbins’ direction outstanding.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free