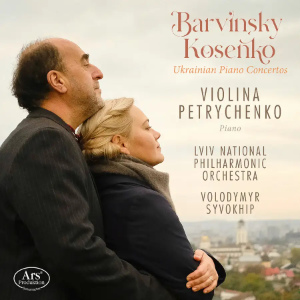

Ukrainian Piano Concertos

Vasyl Barvinsky (1888-1963)

Piano Concerto in F minor (1913-1937)

Victor Kosenko (1896-1938)

Piano Concerto in C minor Op.23 [49]

Violina Petrychenko (piano)

Lviv National Philharmonic Orchestra/Volodymyr Syvokhip

rec. 2024, Lviv Philharmonie, Lviv, Ukraine

First recordings.

Ars Produktion ARS38514 [69]

Ukraine is in the news these days sadly not for its rich musical heritage. The nation has given birth to distinguished composers, including Bortniansky, Berezovsky, Khandoshkin, Roslavets, Lyatoshynsky and Silvestrov. More well-known Russian and Polish composers were born in what is now Ukraine, among them Glière, Szymanowski and Prokofiev.

I had been unfamiliar with Barvinsky and Kosenko. As an avid collector of rare piano concerto recordings, I am delighted to add this fine release to my library. It complements my collection primarily built around the magnificent Hyperion series of Romantic piano concertos.

Barvinsky’s single-movement concerto was reconstructed in 1993 from a piano reduction. Barvinsky, born in Ternopil in Western Ukraine, endured persecution by the NKVD during Stalin’s Great Purge. His papers and books were publicly burned, and he was sentenced to ten years in a Gulag in the Mordovian Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic. Upon his release in 1958, seven years after Stalin’s death, he began to reconstruct the works that had been destroyed. Unhappily, he passed away before he could complete the task.

I find Barvinsky’s concerto the more original here, with more immediate effect. It begins with a relentlessly pounding low drumbeat, accompanied by deep woodwinds. The piano enters, and adds to the percussive soundscape by mimicking tolling bells. This striking effect lasts for two minutes. In some respects, it reminds me of the famous opening of Rachmaninoff’s Second Concerto. The music then transitions into dance-like rhythms, but here the similarity to Rachmaninoff ends.Barvinsky infuses the work with folk-like elements and vibrant orchestration. The dance is interrupted by introspective passages from both the piano and orchestra; it occasionally becomes romantically intense as they harmonize. The material, thematically delightful, leaves one to ponder what the oppressive minds of the NKVD found objectionable in this fine romantic music.

Victor Kosenko’s concerto was left incomplete at the time of his death, with a fully composed first movement and fragmentary sketches for the second and third movement. He was renowned for his pianistic virtuosity in the city of Zhytomyr, where he taught at the Music School. He composed many of his solo piano works and related pieces during his time there.

Under Stalinist rule, conditions in Ukraine were extremely harsh. Kosenko lived in poverty, but he cooperated with the authorities by allowing other families to live in his apartment. (In recognition of his efforts to promote authentic Ukrainian national music, he was awarded a three-bedroom apartment in the city.) By 1938, Kosenko’s health had deteriorated, and he succumbed to kidney cancer in October. Earlier that year, Nikita Khrushchev, then the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Ukraine, personally awarded him the Order of the Red Banner of Labour.

Kosenko intensively studied Moldovan folk music. His compositions blend a late Romantic idiom with the national musical style of his country. While his music does not directly quote folk songs, their harmonies and modes permeate his works. By composing in this manner, he adhered to the Socialist Realist agenda imposed by the Moscow government on its composers. As a result, his concerto does not sound as distinct as Barvinsky’s. Due to the incomplete state of the rest of the concerto, for many years only the Allegro first movement was heard. The influences of Liszt and earlier Germanic composers are apparent.

I find the concerto not as melodically memorable as Barvinsky’s, although it does feature one theme with a lyricism that would befit Hollywood. The first movement, nearly 24 minutes long, feels too extended for its content, and meanders too much. The second movement, Andante con moto, starts with a solo cello playing a mournful theme; the piano makes a bold entry after the first 90 seconds. Thezre are languorous sections, but the movement often seems to overexert itself to make an statement, with the piano’s dominant interpolations. The final movement is a mix of boisterous dancing and grand orchestra/piano declarations. It culminates in a triumphant peroration that brings the concerto to a rousing close

Despite my reservations, I am confident that repeated listening will yield positive results. (I have already listened to Kosenko’s piece three times.) I am happy to conclude my discussion on a positive note.

The performances of both concertos leave little to be desired, with outstanding pianism and a very commendable orchestral contribution. The excellent recorded sound features a well-balanced yet bold piano image and a striking orchestral palette. The booklet – in English, German and Ukrainian – gives detailed biographical information about both composers, along with more generalized musical detail.

Jim Westhead

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free