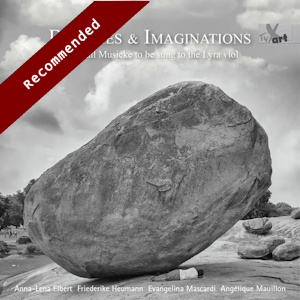

Dreames & Imaginations

Poeticall Musicke to be sung to the Lyra viol

Anna-Lena Elbert (soprano)

Friederike Heumann (viola da gamba, lyra viol)

Angélique Mauillon (harp), Evangelina Mascardi (lute)

rec. 2023, Église de Franc-Warêt, Namur, Belgium

Texts included (with German translations)

Reviewed as a download

TYXart TXA21162 [64]

Hardly anywhere in Europe has such a large repertoire of songs for voice and lute been created as in England in the first quarter of the 17th century. Only the French airs de cour, which at that time were conceived for the same scoring, can be compared with them, but in Italy songs were written in the modern monodic style, for voice and basso continuo.

There are two meaningful differences between English and French songs. First, the former could often be performed in a different line-up; for instance, with voices and instruments. Dowland’s songs, which today are considered the main representatives of the genre, were published in two to four parts, which allowed for various ways of performing them. Second, the voice(s) could not only be accompanied by a lute, but also by a viol. The Second Booke of Songs and Ayres by Robert Jones mentions lute, bass viol and lyra viol as accompanying instruments.

Nothing about his roots and musical education is known. In New Grove, no year of his birth is mentioned. The disc which is the subject of this review mentions “ca. 1577”, which may be based on more recent research. The first sign of Jones’s existence dates from 1597, when he graduated BMus at Oxford. In 1600 he published his first book of songs, and in 1601 he contributed to the collection of madrigals in honour of Elizabeth I, The Triumphes of Oriana. In 1607, he published a collection of madrigals of his own pen.

In his first book the songs are offered in alternative versions for solo voice and for four voices. The second, third and fourth books also include songs for more than one voice, whereas in the fifth and last book he returns to strictly solo songs.

It seems that Jones didn’t meet universal approval in his capacity as a composer. In the preface to his fourth book he greets “all musicall murmurers”. This is quoted in New Grove, but the author of the article does not specify what kind of criticism Jones encountered. He himself is not very complimentary about Jones’s songs either. That makes it all the more remarkable that his second book has been the subject of at least two recordings. The first comprises the complete book, although in a number of songs stanzas have been omitted. The disc was released by the Spanish label la mà de guido in 2009; the performers are the two members of the ensemble Cantar alla Viola, with Fernando Marín playing the lyra viol. That is the ensemble’s specialism, and it is understandable it turned its attention to this book, as it is the first in history which includes a tablature for the lyra viol, or, as it is called, the viola da gamba in leero fashion. There is no unanimity among scholars and performers to what extent the lyra viol is a particular instrument, or a common viola da gamba played in a special manner. In the booklet to the present disc viola da gamba and lyra viol are mentioned side by side.

The programme is extended with instrumental pieces and some songs by contemporaries of Jones. The most famous of them is Tobias Hume, who was a professional soldier, but also a viola da gamba virtuoso, who considered the lyra viol as the lute’s equal, an assertion which was vehemently rejected by John Dowland.

William Corkine published two books of songs which also include some pieces for lyra viol. Some songs have an accompaniment of a bass viol alone. In addition, he left some dances and variations on popular grounds. Walsingham was a popular Elizabethan ballad tune; several composers wrote variations on it, among them William Byrd.

Thomas Ford was a professional viol player. He was in the service of Prince Henry, and later King Charles, whom he served until the Civil War in 1642. His music for lyra viol(s) is reckoned among the best of the time, and indicates that he must have been an excellent performer himself.

John Danyel was born in Wellow, near Bath, and studied at Christ Church in Oxford. In 1603 he received here the degree of BMus. In 1606 his main work, the Songs for the Lute, Viol and Voice, was printed in London. In 1625 Danyel is mentioned as one of the royal musicians. Danyel was one of the main composers of songs, but his extant oeuvre is small. The Passymeasure Galliard is a piece for lute solo, but performed here at the harp. This instrument was used in early 17th-century England; William Lawes composed a set of Harpe consorts.

Despite the critical comments on Jones’s songs in New Grove, I quite like them. I think they deserve their place in the repertoire of lute songs, and the role of the lyra viol makes them even more interesting and attractive. I did not like the performance by Cantar alla Viola very much; the performances offered here are much better. Anna-Lena Elbert has a lovely voice, and I very much enjoyed her performances. She is not an early music specialist, but she seems to feel completely at home in this repertoire. Stylistically her performances are entirely convincing, for instance in the ornamentation department. She pays much attention to the text; each word is clearly understandable. She also characterises each song very nicely, which makes sure that the content is effectively communicated. The programme includes one song by Dowland (and his Come again, sweet love as a hidden track at the end), which she sings very well and which makes me curious to hear her in a Dowland programme. Considering that she is a native German speaker, her command of English is admirable. Given that even English performers mostly use modern pronunciation, it may be too much to expect historical pronunciation here.

The instrumentalists are perfect matches and the instrumental works are given excellent performances, which are subtle when needed, and explore the dynamic possibilities to good effect. It is always nice to listen to music for lyra viol; I tend to share Tobias Hume’s opinion, and Friederike Heumann does everything to prove him right. The role of the harp is surprising in that it is seldom involved in recordings of English repertoire of the early 17th century, but in the piece by Danyel it shows that it is a perfectly qualified alternative to the lute.

Given the fact that Jones’s songs are seldom performed, and the way the music on this disc is interpreted, there is every reason for a special recommendation.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Robert Jones (c1577-1617)

Love wing’d my hopes

Whither runneth my sweet hart

William Corkine(fl 1610-1612)

Walsingham

Robert Jones

O how my thoughts doe beate me

My love bound me with a kisse

Tobias Hume (c1569-1645)

Fain would I change that note

Harke, harke

What greater griefe

John Danyel (1564-1626)

Passymeasure Galliard

Robert Jones

Now what is love

Come sorrow come

Thomas Ford (c1580-1648)

Coranto

Robert Jones

Dreames and Imaginations

Thomas Ford

A pill to purge Melancholie

John Dowland (1563-1626)

Prelude

If my complaints

William Corkine

Pavin

Coranto

If my complaints

Robert Jones

Fie fie

Me thought this otjer night

[hidden track]

John Dowland

Come again, sweet love