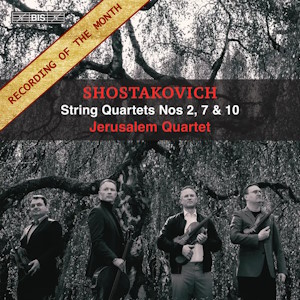

Dimitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

String Quartet No. 2 in A major Op. 68 (1944)

String Quartet No. 7 in F sharp minor Op. 108 (1959-60)

String Quartet No. 10 in A flat major Op. 118 (1964)

Jerusalem Quartet

rec. 2024, Markus-Sittikus-Saal, Hohenems, Germany

BIS BIS2654 SACD [75]

This disc of contrasting string quartets by Shostakovich is the Jerusalem Quartet’s first recording for BIS. It’s a welcome return by them on record to the composer after a long gap, following a series of excellent recordings of some of the quartets on their previous label, Harmonia Mundi.

Shostakovich was an experienced, established composer when he started writing his string quartets. The Quartet No. 1, written in 1938 in the aftermath of the infamous Pravda criticism of ‘Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk’, is classically conceived, structurally and stylistically, and markedly sunny, perhaps broadcasting the message and impression he thought he ought to give. Whatever his motivation, the contrast with the String Quartet No. 2, the first on this disc, is extraordinary. Composed six years later in 1944, its darker tone reminds us of the historical context, and formally it is innovative. The first two movements hark back to baroque models, with an ‘Overture’ followed by a long second movement entitled ‘Recitative and Romance’. Then the structural model changes: the third movement is a short waltz, and the work concludes with a Theme and Variations based on a Russian protyazhnaya song (a melismic folk melody). There is nothing quite like it in the quartet canon and the players need to be supremely adaptable to take the changing structures and developing idioms in their stride. The Jerusalem Quartet do all this apparently effortlessly, exuding a certainty about the direction of the work as a whole and guiding us along a coherent path towards its conclusion. I loved the way they handle the combination of polyphonic writing and strange tonality in the first movement by treating it as a confident quasi-Beethovenian creation. The second movement ‘Recitative’ is riveting. The Jerusalem’s First Violin, Alexander Pavlosky, compels our attention throughout with his wonderfully sustained vocal line and the self-effacing support he receives from the other quartet members is a testament to their many years of playing this work together. The Beethovenian mood returns in the ‘Theme with Variations’, where the unremarkable folk melody is transformed into a series of highly inventive movements, played here with an apparent spontaneity which belies the technical control and interpretative authority this group possesses. The relish with which they play the coda, a final synthesis of the whole Quartet, is glorious, the wonderful modal chords resonating for the listener long after the music has actually stopped.

The Quartet No. 7, written in 1960, is marked by its brevity (it’s the shortest of all fifteen quartets) but also the focus on a very specific texture throughout. Shostakovich directs the players to play con sordino (‘with mute’) for large parts, indeed over half, of the Quartet’s length. As Andrew Huth points out in his excellent booklet notes, this is not really a question of reduced volume, given that skilled string players can produce the quietest of sounds without mutes, more the composer’s interest in the sonority of the thinner sound of the muted string and the contrast when the mute is removed. The Jerusalems play this unbroken three movement work with meticulous care for those sonorities and the effect is mesmerising. From the chromatic unwinding of the opening phrase by the first violin to its extraordinarily effective inversion in the finale, they are alive to the delicacy of Shostakovich’s invention and the subtlety of their playing is exemplary. Perhaps most striking of anything they do in this Quartet is their treatment of the ending of the finale, really almost a fourth movement, where it takes nerve and judgement to follow Shostakovich’s marking of morendo (‘dying away’) as the music’s momentum seems to fail and inertia increases. The effect here is profoundly atmospheric and I wished the silence between the end of this track and the next on the CD was longer.

The final work on the disc is the Quartet No. 10 from 1964. It’s perhaps more immediately approachable than No. 7, the first impression in the Andante opening movement being one of almost relaxed and gentle contemplation, played in an understated way by the Jersualems here, which only makes their ferocious Allegretto furioso second movement the more striking, indeed terrifying at times. The theme and variations which constitute the central Adagio are unfurled with precision and lyricism and the subliminal dialogue between Alexander Pavlosky’s violin and Kyril Zlotnikov’s cello unfurls with a solemn beauty. After this the start of the finale can be deceptively difficult to bring off. The viola has an a slightly gritty sounding almost anapestic melody at the start, which I think needs to sound unstudied and almost conversational, and it’s really well judged here by Ori Kam. The way the rest of the group take up that theme and its development into a sort of rustic, almost dancelike, melody again shows their complete ease in this world of shifting idioms and influences. Once more, this is a quartet which ends with muted strings, slowly fading. In this performance it has a more conclusive and settled feel to it than that of the Quartet No. 7, we feel here that perhaps there has been some sort of resolution.

It’s good news that the Jerusalem Quartet is recording Shostakovich again and I’ve thought a lot about what makes them such an effective ensemble in this repertoire. One of the things I keep coming back to is the cohesion of the sound. I’ve just mentioned Ori Kam’s playing above, and it’s striking throughout all of these quartets how brilliantly he straddles the violins and cello in timbre and dynamics. Even in the world of phenomenal musicianship all professional quartets inhabit, he seems to me a rare talent.

Talking of viola players, a reminder that we’re lucky on MusicWeb to have some of Alan George’s thoughts on a number of the quartets, including two of those on this disc, here. (the rest will come – Len)

Partly as a result of the advocacy of Alan and the Fitzwilliam Quartet for the Shostakovich Quartets, we have an embarrassment of riches to draw on these days in terms of recordings, but I’d say the performances here are as good as any in the catalogue. Freshest in my mind in terms of comparison is the performance of the Cuarteto Casals of the Quartet No. 2. This is part of the first volume of a projected complete cycle, ironically on the Jerusalem Quartet’s old label Harmonia Mundi (HM 902731.2), released in late 2024. The set as a whole is outstanding and the Casals’s performance of No. 2 has perhaps more of a sense of discovery than the Jerusalem’s, a real freshness. At its centre, the second movement recitative is overwhelmingly dramatic, less rhetorical than the Jerusalem’s performance. It’s a fascinating contrast. I wouldn’t want to be without either.

The sound on the BIS SACD is absolutely superb, thrillingly alive and resonant. BIS is owned by Apple and one aspect of that is that BIS records are invariably offered on Apple on its music service as a special ‘Dolby Atmos’ stream or download. For music I am not reviewing, I’ve often used this option for convenience, especially when out and about. Out of curiosity I made a comparison with the sound on the disc and the Apple Music version. In short, the disc sound has more depth, feels more open and seems to have a wider dynamic range. From some of the assertions made by Apple about its delivery of music in ‘Atmos’ format one could be forgiven for wondering if it’s worth seeking out the physical product or FLAC (or similar) downloads anymore. No question in this instance at least.

Dominic Hartley

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free