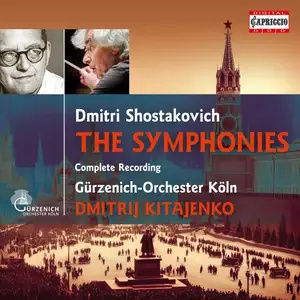

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

The Symphonies

Gürzenich-Orchester Köln/Dmitrij Kitajenko

Special feature: The Cologne Shostakovich Project (interviews in German)

Sung texts in English only

Capriccio C7435 [12 CDs: 770]

Dmitry Shostakovich died fifty years ago. For some, the tonally argued multi-movement symphonic form, dating back to Haydn, died with him – but not his symphonic cycle. These fifteen works, or many of them, seem to be ubiquitous on disc and in the concert hall. Indeed, the disc and concert hall performance can be the same thing: the LSO are now playing all fifteen live in London, and releasing them on their own label. Thirty to forty years ago, one expected a concert to begin with a Beethoven overture (Egmont or Coriolan maybe), followed by a concerto by the same composer or by Mozart; the second half would contain a symphony by Beethoven, Brahms, Dvořák or Tchaikovsky. Sometimes one heard a symphony by Bruckner, Mahler or Shostakovich, but it was seen as a very special event, whereas now their symphonies feature on many more programmes.

Dmitrij Kitajenko and the Gürzenich Orchestra Cologne recorded this set in 2002-2004 and issued it first as a series of SACDs. The present version is stereo CDs, available only on a physical medium. Dan Morgan, in his initial consideration of this cycle for MusicWeb (review), admired the sonics. He judged the stereo layer nearly as impressive as the SACD layer of those hybrid discs. Sometimes, he had to adjust the volume when switching between discs. There is one complete symphony or two on each disc, except No.7 (the first two movements follow No.6 on disc four, the last two movements precede No.9 on disc five).

No.1 is remarkable for a nineteen-year-old student’s graduation piece. While not a great work, it shows much of the mature Shostakovich style to come. The score suggest a playing time of 33 minutes. Kitajenko takes 34:38, perhaps taking his time more than some others over the slow movement (10:13 versus Neeme Jaärvi’s 9:08, for instance). That Lento, beautifully led by a fine solo oboe, announces the winds as a strength of the orchestra. So, this sometimes raucous work is very impressive, and the live sound is upfront, giving any subwoofer a workout.

Symphonies 2 and 3 are notoriously much less enjoyable than most in the cycle. They were propagandist, and what the composer himself later called “youthful experiments”. No cycle will stand or fall by the performance of these works. Kitajenko takes the only possible approach, unapologetically playing them as if they were masterpieces. The Prague Philharmonic Chorus signs well the Soviet dawn celebratory final texts. These are single-movement symphonies, but helpfully there is a track for each section.

No. 4 is the first essential work in the cycle. It requires a huge orchestra (eight horns and much percussion). Kitajenko’s live account runs for 69 minutes against the score’s suggestion of 62 minutes. That is reflected in some slightly sluggish moments but nothing is really dragged out. The narrative of this amazing piece is as compelling as it must be. Again, the recording is imposing in its colour and realism.

No. 5, the most played of these works still, is a studio recording, and offers some beautiful playing. It is a good performance, if not among the most authoritative accounts, although the finale brings it to an exhilarating close.

The three-movement Sixth, which the score says plays for 35 minutes, takes 32:47 here (the composer’s son Maxim Shostakovich takes 32:16 in his cycle with the Prague Symphony Orchestra on Supraphon). Its unusual structure, a long opening Largo followed by two shorter faster movements (an allegro, then a presto) poses issues of relative tempi for the conductor. Kitajenko’s choices are persuasive, and the playing is very fine, not least the cor anglais in the opening lament.

In the live account of the “Leningrad” symphony, No. 7, the orchestra rise to the work’s demands superbly well. Kitajenko really knows his way round this work, and brings out its poignancy and power. This is one of the best performances in the cycle, and bears comparison even with Bernstein’s Chicago SO version on DG, also live.

No. 8 is another concert performance, and has much the same virtues. The Cologne players are always idiomatic, no doubt with Kitajenko’s experience in the repertoire to guide them across this two-year project. No. 9 is in five movements, all of them short, and is usually all over in about 25 minutes. Its wit, irony and even occasional frivolity are brilliantly caught in this studio performance. The players seem to relish their often quirky passages.

The Tenth Symphony is one of the great ones, maybe the greatest of all the purely instrumental symphonies in the cycle. The authoritative Mravinsky in Leningrad on Erato in 1976 (48:08) and the benchmark Karajan in Berlin on DG in 1967 (51:04) confirm the score’s suggested 50 minutes. Kitajenko’s 58:50 slightly impairs the flow at times, especially in the last two movements. Even so, the playing and feeling for the eloquence of this work, especially in the incomparable first movement, more than save the day in another very good performance.

No. 11 “The Year 1905” has cinematic aspects – as the title and the individual movement titles suggest. Kitajenko’s 65:22 timing goes against the score’s guideline 60 minutes, but this if anything contributes to atmosphere, especially in the icily tense “Palace Square” first movement. The second movement’s fugue is athletic, the climactic attack on the demonstrators devastating. The slow movement’s memorial to the fallen is as touching as the Tocsin finale is inspirational in its summing up. The final stroke of the alarm bell continues to resonate after all other sounds have ceased, an effect ideally captured by the recording.

No. 12 “The Year 1917” also has programmatic associations, but is not in the same league as its predecessor, and often seen as the weakest of the composer’s mature works. It is nonetheless well served by the fine performance here, so can be fairly judged in its best light.

The final trilogy is varied, and each work is of high calibre. Nos.13 and 14 are vocal works, and No. 15 is purely instrumental. The Thirteenth, written in 1962, is for bass soloist, a male choir of basses singing in unison and full orchestra. It sets the poetry of Yevtushenko, the opening “Babi Yar” sometimes used as the title for the whole piece. The score asks for “40-100 basses”. I do not know how many there are in the Prague Philharmonic Chorus, but they are a professional group, so 100 would be an awful lot. They make a splendid, focussed sound at each dynamic level. The Armenian bass Arutjun Kotchinian has a rich warm basic sound, weighty when it needs to be but with flexibility and lightness in more confiding moments. Kitajenko’s performance is haunting, as it must be for this mighty work.

If that is not the greatest in the cycle, it might be because its successor runs it close. No. 14 is a song cycle for soprano and bass soloists, a group of 19 strings, and some percussion – fascinating textures are thus deployed, often with a brilliantly brittle sound. Bass Kotchinian is now joined by Marina Shaguch. Her soprano is not always smooth-sounding at the top of the range, but always very effective in her often edgy music. Kitajenko supports his singers very well, in another strong addition to the set.

No. 15 is often said to be enigmatic, even elusive, but it uses some of the same textures as No. 14, especially the bright percussion, with the humour and irony we heard in No. 9. It is not the place to look for summation perhaps, but the finale and especially its coda make a fascinating envoi in Kitajenko’s fine interpretation. The composer lived another four years but there were no more symphonies, and it would be difficult to imagine a better conclusion to the cycle than this.

This is overall a very fine cycle. There are many very impressive performances, and certainly none which lets the cycle down. Kitajenko is very consistent in his interpretations, which are idiomatic, even central in conception, with no eccentricities of tempo or phrasing or balance. The orchestra is very good, and often produces the sense of drama and spectacle one needs for parts of these works.

The 63-page booklet in English is a useful guide to the symphonies, with sung texts also in English but no Russian originals. The sound is splendid, often with great impact, atmosphere and realism. The recording levels vary a little between discs, but it is easy to adjust volume to produce a convincing image at all dynamic levels. I have a few SACD originals. On direct comparison, they are only marginally superior to these stereo CDs played through a surround system using an amplifier with an “all channels” option. There are many competitors in the catalogue, but Kitajenko’s set in this incarnation remains one of the leading cycles.

Roy Westbrook

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Recording details

3-7 July 2004 (Nos. 1 and 15)

7-11 February 2003 (No. 4)

15, 17-18 September 2003 (No. 7)

28 June – 2 July 2003 (No. 8)

12-17 February 2004 (No. 11)

live, Philharmonie Cologne, Germany

2002-2004 (Nos. 2-3, 5-6, 9-10, 12-14).

Studio Stollberger Strasse, Cologne, Germany

Other performers

Marina Shaguch (soprano, Symphony No. 14), Arutjun Kotchinian (bass, Symphonies Nos. 13-14), Prague Philharmonic Chorus (Symphonies Nos. 2-3, 13),