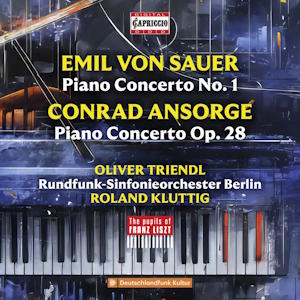

Emil von Sauer (1862-1942)

Piano Concerto No.1 in E minor (1895)

Conrad Ansorge (1862-1930)

Piano Concerto in F major, Op.28 (c. 1924)

Oliver Treindl (piano)

Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra/Roland Kluttig

rec. 2019/22, RBB Saal 1, Berlin

Capriccio C5511 [63]

Emil von Sauer and Conrad Ansorge were exact contemporaries and fellow students of Liszt, in which capacity they have often been anthologised, as they both made recordings. Both also composed. Sauer’s works were for the piano and cast in a rather conventional virtuosic form and in any case, he always maintained he learned more from Nikolai Rubinstein than Liszt. Ansorge was rather more interesting in that he took inspiration from contemporary art and poetry, especially the Jugendstil movement.

This Capriccio disc conjoins Sauer’s First Concerto with Ansorge’s Concerto in F major, composed around six years before his death. The former is a fin de siècle edifice, a calling card concerto, whereas Ansorge’s tends to avoid virtuoso bombast in favour of cyclical structural verities rooted in Liszt’s own concertos but with drama and some whimsy of its own.

Sauer’s concerto was dedicated to Rubinstein’s memory and was premiered in 1900 with the composer as soloist. The ‘Allegro patetico’ indication is largely a feint after the brief orchestral opening as the piano soon begins a powerful fusillade that invokes Litolff as much as Liszt. Stephen Hough coupled Sauer’s E minor Concerto with Scharwenka’s Fourth in volume 11 in Hyperion’s ‘Romantic Piano Concerto’ series (review) and his tempo for this movement is much tighter, mitigating those grandiloquent elements by focusing more on momentum. Oliver Treindl, surely the world’s most hard-working pianist, prefers a degree more horizontality that encourages extremes of expression, whether extrovert or ruminative. The two pianists are largely in accord with the remaining three movements. Sauer’s Scherzo is warmly attractive but includes much up-and-down the keyboard material and a dreaded fugato. His Cavatina is deft and flows sweetly and the finale good-humoured and rather charming with a puckish wit, at least until the conventionally virtuoso final flourish.

After his Lisztian studies Ansorge spent a number of years in America before returning to Germany where he settled in Berlin in 1891 where he remained until his death in 1930. He was also a distinguished teacher and amongst the ranks of students were such names as Wilhelm Furtwängler and Selim Palmgren. Compositions include a Requiem, much chamber music, an Orpheus Symphony and around 75 piano pieces of varying lengths and compositional densities. He began working on the Piano Concerto in 1914, put it aside for the duration of the war and resumed work in 1919. It was premiered in 1924 with Ansorge as pianist.

Apparently, he disclosed that there was a programme to it but never revealed it. The concerto is cast in three conventional movements, uses cyclical elements and is modelled to an extent on Beethoven’s Fourth Piano Concerto. The piano is largely employed as an obbligato protagonist. Its romanticism is quite florid and dramatic at moments, but it also exhibits a rhapsodic freedom that means it sometimes strains against the appellation of a ‘concerto’ – a tone poem with piano may also apply. Michael Wittmann astutely focuses on this idea in his fine notes, citing Falla’s slightly earlier Nights in the Gardens of Spain as precedent. Nevertheless, there is a breezy confidence to the handling of the finale and the work is a malleable, colourful if elusive sonic picture. Intriguing, if not always wholly convincing.

Capriccio’s sonics are first rate and so is the documentation.

Triendl proves a thoughtful, imaginative guide who, as we’ve seen, takes a rather different path to that of Hough in the first movement of the Sauer Concerto. I think the Ansorge is a more intriguing work than the Scharwenka though it’s probably a less convincing concerto.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free