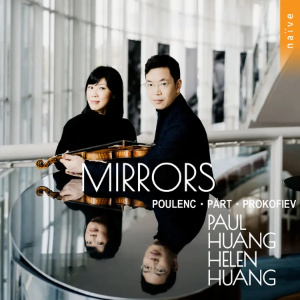

Mirrors

Francis Poulenc (1899-1963)

Violin Sonata, FP 119 (1942-3, revised 1949)

Arvo Pärt (b.1935)

Spiegel in Spiegel (1978)

Sergei Prokofiev (1891-1950)

Violin Sonata No.1, Op. 80 (1938-1946)

Paul Huang (violin)

Helen Huang (piano)

rec. 2024, South Salem, USA

Naïve V8617 [57]

A few moments of reflection (pun intended) make me realise that the title of this album – Mirrors – was not casually chosen and that its references are complex.

Most obviously the word mirrors refers to Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel, the title of which can, I believe, be Anglicised either as ‘mirror in the mirror’ or ‘mirrors in the mirror’. Either way, it is appropriate for the quasi-minimalist structures of Pärt’s composition, with its serene symmetrical patterns, a kind of aural equivalent of the divine geometry to be found in the finest of Islamic decorative schemes. Its perfect abstraction evokes a ‘divine’ order in sharp contrast to the horrors present in the two other works on the disc – this being the central panel in a well-designed triptych. The sonatas by Poulenc and Prokofiev in effect ‘mirror’ one another, in a limited sense stylistically, primarily in the way they hold a mirror up to the experience of war.

Poulenc’s Violin Sonata stands in vivid contrast to the serenity of Spiegel im Spiegel. It was largely written during World II, when France was occupied by the Germans, and it presents an image of the horrors of that experience, and also of the years preceding it. Poulenc clearly had in mind, when writing this sonata, not just the millions of victims of World War II, but also the memory of the great Spanish poet Federico Garcia Lorca, who was killed by Fascist troops, at the age of 38 in August 1936 during the Spanish Civil War (his remains have never been found). At one point, the score is headed by a quotation from Lorca ‘La guitarra, / hace llorar a los sueños’ (The guitar makes dreams cry), the opening lines of Lorca’s poem ‘La seis cuerdas’. The first movement (Allegro con fuoco) opens bleakly, with a craggy theme in the violin accompanied by some percussive writing for the piano – an introduction which has an almost Stravinsky-like quality to it. It is to be the main theme of the movement, returning several times later. Angry outbursts are counterposed with some calmer, more melancholy music, in which these admirable performers are equally impressive. With the two emotional opposites continuing to alternate it is somewhat surprising when, finally, the movement ends on a major chord, as if something has been resolved. In the ensuing movement (marked Intermezzo. Tres lent et calme) the composer is concerned to register both a response to Lorca’s murder and to the multitude of lives lost in the war going on around him as he wrote the music. This second movement contains evocations of Spanish music in a lyrical interlude one might describe as almost rhapsodic, with the violin evoking generically ‘Spanish’ melodies and in the piano writing reminiscences of guitar figures. The playing of Helen and Paul Huang – who seem not to be related, though both come from a Taiwanese background – is particularly fine and richly lyrical in these passages, which are brought to a close by some unexpected chords from the piano, before the movement ends with a rather strange glissando and an enigmatic coda. In the booklet notes both musicians are interviewed by Pierre-Yves Lascar in the course of which Paul Huang says of this sonata by Poulenc, “His melodies are fleeting and punctuated by frequent bold contrasts, in which a lyrical moment will be suddenly interrupted by something more angular and dissonant”. He and Helen Huang negotiate Poulenc’s many juxtapositions and sudden transitions in masterly fashion. The third movement is headed by the unusual marking Presto tragico; this seemingly oxymoronic phrase points to the presence in it of the kind of emotional complexity pointed to by Paul Huang in the words from his interview, quoted above. The movement opens passionately, becomes more melodic and less angry and finally subsides into seemingly weary and melancholic slowness before, in a final ambiguity it closes with a coda which initially seems sardonic but which is finally replaced by a return of the anger of the opening movement. Poulenc was less than happy with the completed work, writing in his Journal de mes mélodies that he had tried to ‘testify’ to his passion for Lorca, but that his Sonata for piano and violin was “alas, not the best of Poulenc”. Helen and Paul Huang obviously think more of this sonata than its composer did, and so do I. Indeed this performance is a close rival for best recording of this work, to that by Patricia Kopatchinskaja and Polina Leschenko (review).

Perhaps not quite so outstanding, but still a rewarding performance is the interpretation of Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata which closes the disc. One highlight comes in the opening Andante assai, in which Paul Huang’s playing of the passage which the composer described as resembling “wind passing through a graveyard”. Mr. Huang’s playing of this passage is free of exaggeration, yet captures all its quasi-gothic horror, and somehow evokes not just a graveyard so much as an entire battlefield. Elsewhere, the two booklet interviews mentioned earlier draw attention to passages which a reviewer might choose to mention, as when Paul Huang says of the last movement that it is “a frenetic folk dance, seemingly joyous at first but gradually moving towards a dramatic climax in which all the thematic material heard in previous movements (wind over the gravestones, church bells, sounds of battle, etc.) collide in chaos”. As in their performance of the Poulenc, Helen and Paul Huang articulate just about perfectly the complex emotions in the music.

This is a fine album characterised by musical insight and sensitivity, as well as by an utter honesty of response. We shall surely hear more of these two accomplished musicians. One minor reservation is that the recorded sound is neither as bright nor as spacious as we expect nowadays, but one’s ears soon adjust. This is very well worth hearing, especially for the superb interpretation of Poulenc’s solitary violin sonata.

Glyn Pursglove

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free