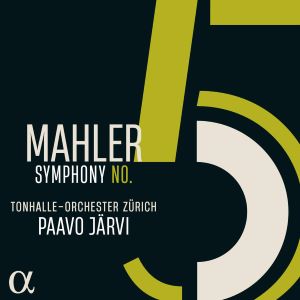

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor (1901-1902)

Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich/Paavo Järvi

rec. live, 2024, Tonhalle Zürich, Switzerland

Reviewed as a 24-bit/96khz stream

Alpha Classics 1127 [70]

In February 2024, Estonian conductor Paavo Järvi and his Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich started a new Mahler cycle for Alpha Classics, which, according to the orchestra’s website, will continue over the next few years. Needless to say, Mahler cycles are a very crowded field as of 2025, but Maestro Järvi’s pedigree and demonstrated success with large-scale symphonic works by Mahler, Bruckner, Shostakovich and others give hype to this new cycle, and the Zürichers already have a rather highly-acclaimed Mahler set with David Ziman under their belt. The Fifth, being one of the most virtuosic and powerful works among the composer’s oeuvre, is a wonderful place to start, since it’s as much a showpiece for the orchestra as it is for the conductor’s structural grasp.

The opening Trauermarsch (funeral march) is impeccably paced by presumably Philippe Litzler, one of the two “Solo-Trompete” of the orchestra, who happens to indicate Mahler’s Fifth as “perhaps” his favourite piece in his profile on Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich’s website. I like how much time and space Järvi allows the solo to take shape before the orchestra joins in (CD 1, track 1, 0:02-0:27), and the quarter-note triplets are correctly kept in tempo as the call ascends in an arpeggio (0:23)–many trumpeters broaden the triplets here, despite Mahler’s flüchtig (fleeting) indication. We soon get a clear idea of the soundstage created by the musicians and engineers, when the orchestral tuttis comes in at ff. It’s a sufficiently deep and wide acoustic, with the engulfing tam-tam atmospherically reverberating in the background (0:57-1:13) before the strings enter with the primary theme. I would’ve liked more dynamic range on the louder end when the funeral march returns (2:22-3:02), as the tuttis here are supposed to create an intensified recurring theme, a brilliant feature that Mahler likes to include in movements with rotating form. When it’s the first theme’s turn to be intensified, the canon-like entries in the strings are sensitively shaped, however more stereo separation between violins and violas and cellos in the first phrase would have been welcome (3:02-3:12). Järvi appropriately launches his band into a frenzy at the “Plötzlich schneller. Leidenschaftlich. Wild” (“Suddenly faster. Passionate. Wild”) section (5:13), and the control they’re able to maintain here deserves praise indeed. My disappointment with the first movement mainly lies in the fff cry of anguish towards its end (11:00). Here, Mahler requests that most of the winds raise their bells (Schalltrichter auf!), and the dynamic marking should make it the most devastating moment in the symphony so far, but Järvi hasn’t saved enough audio headroom for this spot in my opinion, as it sounds too close to the numerous ff outbursts in power. As a consolation, the final pizzicato that ends the movement and its resulting echo are richly captured, displaying the bass-rich sonics of the recording (12:25-12:28).

Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz (stormy movement, with greatest vehemence) is the expressive indication for the second movement, and listeners probably wouldn’t need the score or booklet notes to tell them that given the way the Zürichers tear into the music at the opening. The second theme (CD 1, track 2, 1:30-3:31) is characterized mournfully, with the lamenting line beautifully sung by the cellos. I especially like the depth of that section’s tone here, as it needs a firm core in order for listeners to not be too distracted by the repeating staccato figures that are reminiscent of the first movement’s trumpet call, from the rest of the orchestra. As this movement is similar to the first in that it also features a rotating form in its exposition (i.e. first theme, second theme, then intensified versions of each), an important test for the interpreter here is that each of the themes must be properly calibrated in expressive intensity so that the progression of this structural design could be realized. I’m happy to report that Järvi passes with flying colours here – he does this largely by not overplaying either of the themes in their initial appearances, while paying close attention to the orchestrational changes and expressive markings that Mahler prescribes for their returns. This is as concrete an example of the maestro’s great structural grasp as I could find. Unfortunately, I realize that we soon also have a negative example: the dramatic chorale towards the end of the movement (12:05-13:40) that foreshadows the symphony’s triumphant conclusion is taken at a rather broad pace, quite a bit broader than what I’m used to hearing, and what I think would be suitable for the narrative arc of the work. At key moments throughout this episode, Mahler indicates Pesante (heavy), Nicht schleppen (not dragging) and even Vorwärts (forward), with only a Ritenuto (slowing down) in the last few bars before the opening theme recapitulates. We must also remember that this is but a foreshadowing of the glory that we’ll eventually arrive at, and not the thing itself. By the way, what happened to our beautiful tam-tam near the close (14:11)? That stroke is marked fff by the composer there, the only percussion instrument to have that honour, and Mahler even asks for it to be klingen lassen (let vibrate), but all I can hear is the timpani and maybe some bass drum.

What a contribution from Ivo Gass, the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich’s “Solo-Horn”, in the dancing Scherzo that incorporates both waltz and ländler elements. His tone is bold but refined, forceful but elegant. One thing that turns me off from this movement would be a strident, grating tone from the Corno obligato (lit. mandatory horn)–this is the longest movement in the piece as well, so that’s not an insignificant consideration at all. At just under 18 minutes, Järvi’s leisurely tempo here is well-judged too, as the composer asked for it to be “Kräftig, nicht zu schnell”(“forceful, not too fast”). The Tempo I towards the end of the development that leads to the recapitulation is one of the best-executed I’ve ever heard, with tempo changes implemented in an organic way, and the orchestral details registered with realism, especially the taps from the Holzklapper (clapper) (CD 1, track 3, 10:32-11:12). The maestro also understands the tension that such a massive crescendo could generate when sharply torn off into complete silence, as evidenced by his judicious observation of the breath mark (11:11-11:12) that allows it to separate from the recapitulation. A very nice touch! Speaking of which, check out the sheer tone quality of the movement’s final cadence (17:44-17:48). If this ending has ever been played with a more polished blend and captured in a more lifelike sound, I’d like to know about it, because it’s just sensational here.

When I saw that the Adagietto being 9:52 in timing, I was low-key excited about this release already. How many conductors throughout recorded history have dragged this alleged love letter from Gustav to Alma into 10, 11, 12 minutes? The answer is probably worse than most listeners think. Unless a maestro’s name is von Karajan, in my experience, most of the time their ponderous takes on the fourth movement simply fail due to tension being lost across the bar lines. It really takes a refined string section who plays and listens to their standmates with utmost sensitivity to produce the kind of tone and phrasing that could sustain an adagio of heavenly length, and that’s not what Mahler asked for here to begin with. Under Järvi, the Zürichers’ violins produce an ethereal tone that reminds me of the seminal 1973 account by the Berliner Philharmoniker under their aforementioned Austrian maestro. Their phrasing is inflected with longing portamenti (slides between notes), and more importantly, a sustained tone with no audible gaps between phrases and breath marks (CD 1, track 4, 0:12-1:12). This is key to maintaining the tension that’s lost in so many recordings of this movement, as mentioned above. The Fliessender (more flowing) middle section (3:51) takes the intensity up a notch, and has plenty of room to hasten given Järvi’s smartly judged basic tempo at the start. Harmonic inflections that this love song is famous for, including its many achingly beautiful appoggiaturas and suspensions are given painstaking care to ensure that they make their expressive impact without degrading their noble intentions and turning the music into a cloying mess. I truly enjoyed how the Adagietto is done here – kudos to Järvi and his ensemble.

At last we arrive at the Rondo-Finale, where the symphony’s narrative arc wraps up in the most majestic way possible, with a grander and harder-won peroration of the chorale that was hinted at in the second movement. The successive entries of each instrument at the introduction have a level of clarity and separation that I’ve rarely heard, even in other recent recordings of this symphony acclaimed for their sound quality (CD 1, track 5, 0:00-0:43). As the movement proper gets underway, I must give credit to the maestro once again for his well-judged basic tempo here, which is brisk enough to be plenty exciting, yet reasonable enough that contrapuntal clarity, a top priority of this movement, to be maintained as textures get denser and denser throughout. The pile up of instrumental lines (5:35-5:45) is a great spot to savour the wonderful stereo separation and spacious soundstage of the recording’s sonics. Structurally, whenever we arrive at the recurring sections where the Adagietto’s theme makes their reappearances, Järvi faithfully realizes the orchestration Mahler utilized to ensure that they’re intensified along the movement’s narrative arc: the first time the violins only accompanied by the rest of the string choir (3:42), the second time also by their woodwind colleagues (6:53), and the final time by both but at a swifter pace and louder dynamics in the winds that go up to ff (11:58). When the chorale makes its triumphal return (13:05), I appreciate how there’s no slowdown here just yet – Mahler only indicated a Pesante twenty bars later, and even then, I’d argue that it doesn’t really need much of an allargando (broaden) at all, so overwhelming is the jubilant climax already. The final section is marvellous in both idea and execution here, with the accelerando till the end (13:52-14:29) well-choreographed so that the tempo doesn’t get too rapid too soon, or get so quick such that the hectic orchestration gets out of control. The way conductors treat the trombone spotlight moment that recalls the oboe and bassoon’s introductory theme is usually a peeve of mine, since it almost never gets enough tone, despite it being marked “alles übertonend!” (“above all in sound!” by the composer. Here, it’s prominent, but could’ve certainly benefited from a fuller and more dominating sonority still (14:01-14:11). The last bars, though, are truly spectacular; remember the sound quality that I raved about at the end of the Scherzo? Well, it’s back, and in even greater splendour than before. Just listen to the reverberation in the hall after the ultimate chord; it’s absolutely glorious, and a testament to both the tonal richness of the Tonhalle-Orchester Zürich and the prodigious abilities of the Alpha Classics engineers (14:25-14:30).

What we have here is an exciting start to a new Mahler cycle that seems to be mightily promising. The sonic presentation is full, clear, deep, realistic; the musical contributions from Järvi and his Swiss band are mostly wise, sensitive, and compelling. Despite entering a field as crowded as Mahler’s Fifth, this release is competitive on a number of key fronts and is as such a welcome addition to any aficionado of the composer and any audiophile of orchestral music.

Kelvin Chan

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free