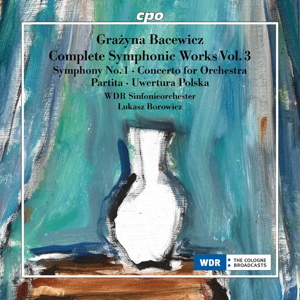

Grażyna Bacewicz (1909-1969)

Orchestral Works Volume 3

Symphony No 1 (1945)

Polish Overture (1954)

Partita (1955)

Concerto for Large Orchestra (1962)

In una Parte (1967)

WDR Sinfonieorchester/Łukasz Borowicz Łukasz Borowicz

rec. 2023, Philharmonie, Köln, Germany

cpo 555661-2 [75]

The death from a heart attack at a tragically early age of the Polish composer Grażyna Bacewicz robbed the musical world of a major voice. It is only right and good that her brilliantly imagined music is now taking its place on concert platforms. A composition student of Nadia Boulanger and a violin student of Carl Flesch, she juggled, as many female artists have had to do, a life as wife, mother, composer and performer. Her output is extensive and all the more remarkable considering what she had to cram into a day. She was a pupil of Boulanger, and as such her music has a rigorous technical backbone, and as a professional, sought-after violinist she had an impeccable ear for orchestral colour.

The earliest work on the disc is her Symphony No. 1, begun in 1942 when she was pregnant with her daughter, who grew up to be the painter Alina Biernacka. Completed in in 1945 and premiered in 1948, it is a substantial work lasting almost twenty-five minutes. I think there are only two earlier orchestral works from the mid-30s including the first of her seven violin concertos. The work is truly impressive in content and structure. The inspiration is kept up for the full twenty-five minutes, each of the four movements having something to engage us. Soundwise, the school of American composers of the early 30s comes to mind, but maybe that is because so many of them studied with Boulanger, and the style is that of the Boulangerie. There is much modal writing, clear, invigorating counterpoint and the vigorous rhythms much encouraged by Mademoiselle. The opening motive is rigorously explored in the seven-minute first movement and the second subject is well contrasted being introduced sul ponticello on the violins. The slow movement begins with a languorous melody on the clarinet answered by the French horn; all very French sounding, but there does seem to be a Polish twist. Szymanowski would probably have been pleased. It builds organically to an impressive climax with pounding timpani. The scherzo is a brilliant show case particularly for the woodwind though everyone gets to shine. It is five minutes long but seems shorter, so engaging is the playful material. The finale sounds once again declamatorily American – sorry; Parisian – and one cannot help being swept up in the excitement. The technical brilliance is extraordinary – and to think it was written in occupied Poland.

Once the communists took over Poland after WW2, experimentation was discouraged and so with the Polish Overture from 1954 we are on familiar territory. There are modal melodies and the asymmetrical rhythms of some folk dances. Pushing ten minutes, it is a substantial work and deserves its place in the concert hall.

Between the overture and the Partita which follows, Bacewicz was involved in a near fatal road accident which forced her to give up playing the violin. The works four movements are still neoclassical in shape but in the third movement intermezzo, the music seems to hint at a deeper darkness and introspection. The mournful clarinet solo, later picked up by oboe and flute, flows through a music that seems at once on a journey but also timeless. As if embarrassed by the introspection the finale is lively folk dance which ends the suite with a bang. The work exists in a version for violin and piano, but such is the brilliance of the orchestration, and brilliance of the players here that I cannot imagine it in duo form.

Polish life change somewhat in the late 50s and early 60s, and so too did Bacewicz’s music. The last two works on the disc take us into the 1960s and much more thorny musical material appears. She has clearly heard the work of her European colleagues and decided to try to catch up – if catching up is what was done. There is more work in tone colours and textures without melody, there is musical space between notes, presumably allowing us to interpret what has happened. Although the concerto is for large orchestra, she frequently breaks it down into smaller unusual orchestral groupings and while there are some extraordinary orchestral colours, low basses with harp and vibraphone are really ear catching, I find the music no different from so much music that crept from under the rubble of post war Europe and I don’t find it very interesting. The last work on the disc and one of her final works, In una Parte,is a study in wide ranging textures which the orchestra brings off very well – but it seems long at seven minutes.

It is clear from all these works that the composer had an extraordinary command of orchestral writing. As a long-standing orchestral musician she knew what every instrument could do and had no qualms about writing extremely challenging, though always appropriate, music for each instrument. Although there is only one work on the disc entitled ‘concerto’, all the works demand players of the highest calibre, which fortunately these members of the orchestra are. Łukasz Borowicz has clearly prepared the works with reverence, and they definitely set the bar high for future interpreters.

The disc proudly proclaims that with this volume 3, cpo have covered all of her works for orchestra. To me this seems to be out by about half a dozen pieces, so I am not sure how they decided what to include and what to leave out.

Paul RW Jackson

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.