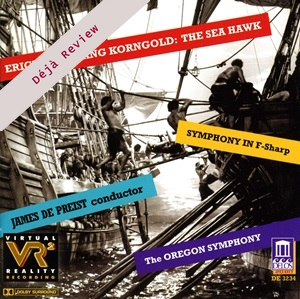

Déjà Review: this review was first published in February 2003 and the recording is still available.

Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957)

Symphony in F-sharp, Op 40 (1952)

The Sea Hawk – film music (1940)

Oregon Symphony Orchestra/James DePreist

rec. 1997, Baumann Auditorium, George Fox University, Newberg, Oregon, USA

Delos DE 3234 [62]

The Sea Hawk was in the swashbuckler genre of film, a 1940 Errol Flynn classic packed full of thrilling naval action, and Korngold rose to the occasion with his score. This potpourri of three sections consists of a Walton-like ‘Main title’ and ‘Finale’, brassy fanfares and driving rhythms, framing a slow, dreamy ‘Reunion’ with its melody hovering dangerously near ‘We’ll gather lilacs in the spring’ (tr1, 03:30). But it serves as a reminder of how brilliant a composer of film music Korngold was after his initial success in 1936 with Anthony Adverse and then another Flynn movie, The Adventures of Robin Hood in 1938. Lush scoring and with melodies heavily influenced by Rachmaninov, the magical entry of the saxophone (tr1, 04:30) is typical of his style.

For Korngold to produce a symphony in the post-war era when so many composers were qualifying this form with adjectives such as ‘chamber’, ‘simple’ or even ‘short’ and only Shostakovich, Vaughan Williams, and, once again, Walton were sticking to their symphonic guns, was a brave move. The music is nothing like the film music, and indeed it transpires he had been working on it for over thirty years. It’s a huge late-romantic work, effectively out of date before he had completed it, but he clearly did not want to travel the path of serialism or atonalism. Its ambiguities lie further in the absence of modality, deliberately avoiding the words ‘major’ or ‘minor’ in the key title, rather leaving it to the implications of the moment. Key relationships are deconstructed, there is none between the first and second subjects of the first movement (F-sharp to C major), the development has a thrilling tension with some allusion to his film style before concluding mysteriously in woodwind dominated passages (tr 2, 08:50) before the recapitulation, where we hear once again the unison theme of the harsh, dramatic material at the start. The Scherzo is a tarantella (with thrilling horn passages which hark back to film scores, tr 3, 08:30) followed by a surreal and sparsely scored trio, while the slow movement is a Mahlerian funeral march, the emotional epicentre of the work. The main theme is a transformed version of the Death March for the Earl of Essex composed in 1939 for another Flynn (and Bette Davis) film, The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex. The build-up from tr 4, 05:10 to one of three climaxes tr 4, 06:20 exemplifies the outpouring of emotionally rich material at this composer’s fingertips. The work ends with a rather abrupt mood swing to a jauntily joyous Rondo, in which the earlier movements are recalled at various places.

This is an excellent performance by the Oregon Symphony [Orchestra] under James DePreist in the surround sound of Delos’s Virtual Reality Recording made in the spatial acoustics of the University auditorium in Newberg, Oregon. The symphony has had its interpreters over the years, the late Rudolf Kempe with the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra in 1972 and Werner Andreas Albert’s 1988 compilation for cpo with the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie, but this is as good as it gets.

Christopher Fifield

See also review by Rob Barnett (September 1998)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site