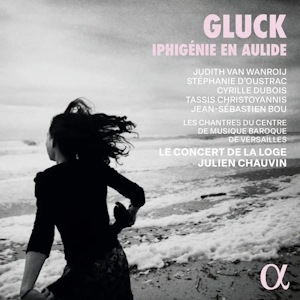

Christoph Willibald Gluck (1714-1787)

Iphigénie en Aulide – Tragédie-opéra en trois actes (1774)

Judith van Wanroij (soprano): Iphigénie

Stéphanie d’Oustrac (mezzo-soprano): Clytemnestre

Tassis Christoyannis (baritone): Agamemnon

Cyrille Dubois (tenor): Achille

Jean-Sébastien Bou (baritone): Calchas

David Witczak (baritone): Patrocle/Archas

Anne-Sophie Petit, Jehanne Amzal, Marine Lafdal-Franc (sopranos): Greek Women

Les Chantres du Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles

Le Concert de La Loge/Julien Chauvin

Booklet with notes in French, English and German, and French libretto with English translation

rec. 2022, Soissons, France

Alpha Classics 1073 [2 CDs:116]

Gluck’s Iphigénie en Aulide is one of the great operas between the eras of Monteverdi and Mozart. It was the work that Gluck designed to establish his reforming operatic art at the Paris opera. France had never succumbed to the 18th century dominance of Italian opera across Europe. The French favoured their own national form for serious subjects, the tragédie lyrique, practiced by Lully and Rameau. Yet Gluck’s opera was a great success: an example of his serious attention to drama and music, supported by staging and acting. Henceforth, he became established as the new leader of French opera.

François-Louis Du Roullet’s libretto draws on Euripides and Racine. In their tragedies, Iphigenia, daughter of Clytemnestra and Agamemnon, must be sacrificed to appease the goddess Diana, so that wind will allow Agamemnon’s fleet to sail to the war at Troy. The Iphigenia myth had been set by many composers before Gluck. His Iphigénie en Aulide held the stage for many years, but was less often produced in the twentieth century. Even now is not as frequently staged as we might expect, given its status. Recordings are valuable because there had been few major ones.

This account, then, is especially welcome. It uses the first 1774 version, and the manuscripts rather than the printed edition. So fairly few dances as the composer initially intended, though he added more in 1775. Also in the 1775 version, the Goddess Diana herself descends, dea ex machina, to bring about the happy ending. Here the score closes after the final chorus, with no direct divine intervention. The high priest Calchas has heard the wishes of the Goddess, who no longer demands the sacrifice.

The very informative booklet note lists the voice types sought for the cast, and a reference to the group of celebrated artists who worked with Gluck at the premiere. Voices needed to be expressive and comfortable with the late 18th century French style of declamation, phrasing and decoration. Those, too, are explained in some detail.

In fact, not all the singers here are of great vocal allure, although all are certainly expressive and persuasive in their roles. But then Gluck the reformer was less interested in vocal beauty or display than in dramatic truth. Agamemnon’s plight must move us, as he faces demands for, but resists, the sacrifice of his daughter. Tassis Christoyannis’s baritone sounds at times slightly ungrateful, but he has one of the score’s plum numbers to close Act 2. In Ô toi, l’objet le plus aimable [Most lovable of daughters], he touches us confronting his situation as a leader in extremis.

As his wife Clytemnestra, Stéphanie d’Oustrac is on fine vocal form. Her Act 3 Scene 6 aria Dieux puissants, que j’atteste [Mighty Gods whom I invoke] is full of ferocious defiance. Judith van Wanroij sings Iphigénie nicely. Her bright soprano suggests well the poignancy of Iphigénie’s position as innocent bystander in her own perilous drama. Her beloved Achille is Cyrille Dubois, already established as the leading French tenor in opera and in mélodie. He deploys his very appealing tenor with lyrical poise despite the demands of the part’s tessitura. As Calchas, Jean-Sébastien Bou brings an appropriate priestly solemnity.

The chorus has a lot to do in this opera. The singers of Les Chantres du Centre de Musique Baroque de Versailles sound engaged and disciplined, and powerful and stirring when required. The authentic instruments of Le Concert de La Loge delight with colour and articulation. Julien Chauvin directs them and his singers with some swift speeds and dramatic flair. The sound is good, immediate and well-balanced, and the notes are unusually revealing of the preparations needed to bring such a score alive. All lovers of Gluck should hear this invaluable issue.

Its only rival is that which John Eliot Gardiner, with his Monteverdi Choir and the Orchestra de L’Opéra de Lyon, recorded for Erato in 1987. That orchestra has modern instruments, but the performance is dramatic and moving. The very fine cast is led by José van Dam’s superb Agamemnon. The recording uses the 1775 text, with a descending Goddess, extra ballet music and a Lully-style closing Passacaille. The Alpha release certainly stands alongside the Erato issue, but given the different texts, neither can displace the other.

Roy Westbrook

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free