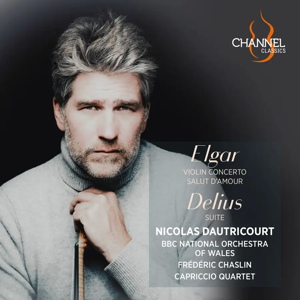

Sir Edward Elgar (1857-1934)

Violin Concerto in B minor, Op.61 (1910)

Salut d’amour, Op.12 (1888)

Frederick Delius (1862-1934)

Suite for Violin and Orchestra (1888, arr. violin, piano and strings, Frédéric Chaslin)

Nicolas Dautricourt (violin)

BBC National Orchestra of Wales / Frédéric Chaslin (piano)

Capriccio Quartet

rec. 2021/2022, BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, UK; Hattonchâtel City Hall, Meuse, France

Channel Classics CCS48725 [78]

The almost universal acclaim won by Vilde Frang’s recording of the Elgar Concerto has made me feel like someone in a Bateman cartoon, namely ‘The Man Who Didn’t Like Vilde Frang’s Elgar’ (review). Still, that’s the way it is, and the latest reappearance of Albert Sammons’ recording of the Concerto (review) only served to reinforce the depth of my lack of identification with her performance. Now along comes another recording, made in 2021, this time by Nicolas Dautricourt with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales directed by Frédéric Chaslin, and it disappoints me all over again.

Let’s get to the point. Dautricourt takes 55 minutes over the Concerto. So, too, it is true, did Nigel Kennedy, in his second recording with Simon Rattle, and Ida Haendel with Adrian Boult (she took 46 with Rattle) – and I dislike both of them as well. The gulf between lithe and indulgent recordings in this work is huge, from Heifetz and Ferraresi at 41 minutes to Dautricourt, Kennedy and Haendel. Sammons took 43. The Elgar is a complex, demanding and long work, but surely in no other major concerto is the disparity in timings so obvious and so perplexing.

Given this, I’m afraid you will have to note my antipathy to this kind of performance and factor it into your thinking as one man’s interminable lingering is another’s sensitive exploration. However, a few things are worth stating. Elfin musing is only viable if it is contextualised within the fabric of an intense, sometimes unstable musical direction. Playing slowly may bring a kind of expressive candour but it invariably courts structural stasis. Dautricourt limps and lurches through the outer movements, slowing then relaunching without sufficient preparation. The orchestra’s bass and brass growl and glower, and counter-themes just about survive, but only just. Passagework at the end of the first movement takes an age, and the music sounds as it sounded to me the first time I heard the concerto over 40 years ago and before I grew up: long, pompous and boring.

There is over-emphatic phrasing even in the central movement though it responds slightly better to the soloist’s tendency towards maximal elasticity. In the finale, an initial impulse is repeatedly brought up short, and all sense of forward drive is lost. The performance becomes, for me, something that had to be endured, not enjoyed. There is very little sense of resolution, or triumph, at the end, though I acknowledge the dogged persistence of vision that Dautricourt brings.

He and the orchestra play Salut d’amour, which is really neither here nor there, but they also play Delius’s Suite in an arrangement by the conductor for the ‘Chausson Concert’ combination of violin, piano and string quartet, a role taken by Dautricourt, Chaslin himself as pianist and the Capriccio Quartet. This was recorded in Hattonchâtel City Hall in the Meuse, a year after the Concerto. The Suite is untypical of mature Delius – even though he, like Elgar, had been a violinist – but it is even more untypical given this arrangement. Both Ralph Holmes with Vernon Handley and Tasmin Little with Andrew Davis have recorded the authentic orchestration, so I can only assume that Chaslin undertook the arrangement as something of a recreational study. The opening movement sounds indulged here – both Little and Holmes are much quicker, as they are in the finale – but the inner two movements sound better, if unfamiliar. Dautricourt sounds more stylish in this lighter, chamber-scaled approach, and his tone also sounds more consistently pure. In the Elgar it comes under strain and his vibrato is not varied or expressive enough. I would like to hear him in the Franco-Belgian sonata repertoire, though.

The Orchestra plays well enough and the recordings in both locations are well judged. Notes are certainly adequate. I didn’t like Frang and I certainly do not like Dautricourt. Who’s next?

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.