Déjà Review: this review was first published in February 2009 and the recording is still available.

Guillaume Dufay (1397-1474)

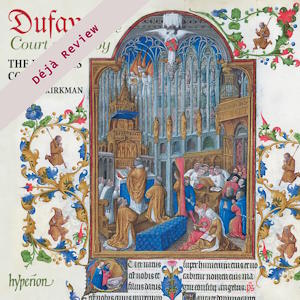

The Court of Savoy

The Binchois Consort/Andrew Kirkman

rec. 2008, Chapel of All Souls College, Oxford, UK

Hyperion CDA67715 [72]

The venerable eight-person Binchois Consort under director Andrew Kirkman has followed the well-established practice of coupling a Renaissance mass with the (secular) ballade on which it is based. For this excellent CD, though, they have also interspersed the five movements of the Mass, Se la face ay pale, with excerpts from the Proper that celebrates the soldier-martyr, St Maurice, a major Savoyard saint and patron.

The CD is really an attempt to recreate aspects of the musical sound world of the Court of Savoy at its height, in the middle of the 15th century. With the improved economic and political fortunes of the Duchy came more opulent artistic achievement: Guillaume Dufay (1397-1474) was at the height of his powers. His Missa, Se la face ay pale is thought to have been composed in the early 1450s for the court of Savoy.

It’s classic in proportion, noble in structure and penetratingly lovely in texture. Given its prominence and provenance, it would be tempting to look for ostentation and superfluous manipulation of emotions in this outstanding piece of writing by Dufay. Far from it. There is invention, accomplished depth and a measure of innovation, although Dufay was working within a well-defined and stable convention. But as the Binchois Consort effortlessly makes plain, it is the power of the composer’s skill in leading us from formula (the process of the mass) to feeling that actually affords the music its greatest impact. They equally effortlessly set out Dufay’s rich interpolation of lines and handling of texture to communicate not grandeur but confidence. This because the many complex passages do not lose us; they enhance our appreciation of the in fact somewhat simple melodies on which the Mass is based.

Is it fanciful to locate this sense of control (distance, almost) in the expansion of Savoyard political power at the time when Dufay was writing? His reflection of the greatness of the Duchy in which contemporary documents suggest the composer’s patrons all believed would certainly not have been unwelcome. But his genius is in having been able to extend this majesty and splendour beyond the political through the sacred into the universal. And it’s such a wholeness of vision that the singers on this CD convey so successfully.

In other words, to the Dukes Dufay was an attribute of, almost a ‘trophy’ to, the grandeur of their court. To Dufay, Dufay was a communicator of a ‘higher’ splendour. This is the vision which the Consort has so successfully captured here. Through perhaps a slower pace than might have been expected in places; through a more leisurely and understated grasp of the Mass’s structure; and through the interspersing of movements as previously described. The music stands in its own right.

From what we know about Dufay the person, it’s unsurprising that his political astuteness (when he came and went from the Court in times of trouble, for example) contributed to the impact of his music: it never ran away with itself, nor took itself too seriously. The integrity of its very monumental stature saw to that. So, too, the Binchois Consort sings without pretension, secure in letting the vocal lines speak for themselves.

Two motets – O très piteulx and Magnanime gentis as well as the ballade, Se la face ay pale – are also to be heard. The tenor of the latter forms the basis for the cantus firmus for the Mass. We know the dates of the motets with unusual certainty: Magnanime gentis was written in celebration of the peace treaty between Louis of Savoy and his brother, Philippe. O très piteulx was composed probably within a couple of years of, and as a stark reaction to, the fall of Constantinople in 1453. The Binchois Consort approaches these three pieces not as slighter second cousins to the Mass, but with as much flexibility, suppleness and insightful subtlety as they deserve. For there is real emotion – joy and distress – almost palpable immediacy, and truly deft contrapuntal writing. These suggest a mature musical reaction to external events of such importance to patron and pilgrim.

So this is a CD to be considered very seriously if the greatest achievements of early Renaissance polyphony are of interest to you. There are four recent recordings. That of Diabolus in Musica with Antoine Guerber on Alpha (908) is undoubtedly the most worthy competitor. In fact, it’s good to have that and this both. For every bit in which the account of Diabolus is rich, that of the Binchois is composed, collected, restrained. It’s not an argument of authenticity or expressiveness: both have both in good measure. The Missa, Se la face ay pale is so central to the repertoire that it can bear multiple interpretations. And that of the Binchois Consort gets as close to the soul of Dufay’s intention as can reasonably be expected.

This is a superb account of Dufay’s Missa, Se la face ay pale, which is a cornerstone of the early Renaissance choral polyphonic repertoire. The performance has flair without show, commitment without stodginess and insight without ponderousness. A worthwhile attempt to evoke fifteenth century court life in southern Europe at a time when so much seemed possible.

Mark Sealey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Introit, Venite benedicti [5:51]

Missa, Se la face ay pale, Kyrie [3:56]

Gradual, Gloriosus Deus [6:05]

Missa, Se la face ay pale, Credo [9:14]

Missa, Se la face ay pale, Sanctus [7:08]

Communion, Gaudete iusti [2:18]

Ballade, Se la face ay pale [3:03]

Missa, Se la face ay pale, Gloria [9:27]

Alleluia, Iudicabunt sancti [5:50]

Offertory, Mirabilis Deus [4:15]

Missa, Se la face ay pale, Agnus Dei [5:03]

Motet, O très piteulx, 1453 [3:31]

Motet, Magnanime gentis, 1438 [6:37]