Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No.1, Op.15 in C major (1800)

Piano Concerto No.2, Op.19 in B flat major (1795)

Piano Concerto No.3, Op.37 in C minor (1800)

Piano Concerto No.4, Op.58 in G major (1805)

Piano Concerto No.5, Op.73 Emperor in E flat major (1810)

Choral Fantasia, Op.80 in C minor (1808)

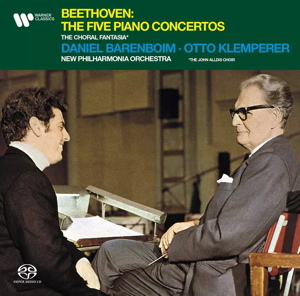

Daniel Barenboim (piano), John Alldis Choir, New Philharmonia Orchestra/Otto Klemperer

rec. 1967, EMI Abbey Road Studios, London, UK

Warner Classics 2173244918 SACD [3 discs: 211]

This famous set has been through various incarnations. Most recently, it was issued as part of a huge boxed set of Otto Klemperer’s EMI recordings of orchestral music on 95 CDs; the box was reviewed by my colleague, Jonathan Woolf. The recordings had been remastered by Christophe Hénault of Art & Son Studio, Annecy in 192kHz/24-bit from the original tapes. Now Warner have gone a step further and issued that remastering of the concertos as SACDs.

The sessions took place in October and November 1967. Barenboim celebrated his twenty-fifth birthday on 15 November 1967, a few days after the project was complete. Klemperer, by contrast, was born in May 1885, so he was eighty-two when he led these performances. Klemperer was famously stern in character and you might think that the combination of a very senior conductor, traditional in his approach, and a much more mercurial young talent such as Barenboim would not have worked. However, the pair found common ground and mutual respect. In his booklet note, Richard Osborne relates that the two musicians first collaborated a few months earlier, in a recording of Mozart’s Piano Concerto K503 (which is included in the aforementioned box of 95 CDs). There was “an immediate rapport” which led to Klemperer being more than receptive to the idea of recording the Beethoven cycle with Barenboim. As a further illustration of their rapport, I was recently told a story by someone who worked at EMI at the time, as part of producer Suvi Raj Grubb’s team, and who attended the Mozart and Beethoven sessions: “As I remember, he and Klemperer got on like a house on fire. I used to keep a log of takes at Abbey Road so I sat in on most sessions. [In the] Mozart K503. Danny had decided to do some embellishments to the cadenza which went on forever and at one point Klemperer began coughing rather loudly, completely interrupting the recording, a kind of protest-without-words, if you like. Completely unconcerned and relaxed, Barenboim threw his head back and laughed. ‘Ah, Herr Klemperer das ist eine Yiddishe Cadenza!’ he said. I’ve never known Klemperer laugh so much – I reckon only Barenboim could do that. The most you could normally get out of him was a lopsided grimace which passed as a grin and which used to terrify me!”

I’ve heard all these performances before, mainly through radio broadcasts; but inexplicably, I’ve never owned the set, so I’ve not had the chance to appraise them in detail. I think one issue in approaching these performances is that we have become so accustomed either to hearing the Beethoven concertos played by HIP ensembles or else, if modern instruments are used, by slimmed-down orchestras; I know that’s true in my case. In such performances fleet tempi are very often the order of the day. I quickly decided two things. One was to set aside any preconceptions which recent performances might have instilled. The other was that I would make no comparisons since these recordings are, I think, sui generis. That said, I have done some comparisons between the newly remastered SACDs and a borrowed copy of the recordings in their 2006 CD remastering by Parlophone Records. I’ll address the question of the remastered SACD sound later; first, some comments about the performances.

Though it is known as Concerto No 2, Op 19, the B flat concerto preceded the C major, Op 15. In the first movement Klemperer immediately sets out his stall; the music is firm and purposeful, notwithstanding which the rhythms are nicely lifted. There’s good interplay between soloist and orchestra. Barenboim plays Beethoven’s cadenza and does so commandingly. The second movement is a true Adagio; we recognise that immediately from the searching, weighty way in which Klemperer begins the movement. Both Barenboim and his conductor take a deeply serious view of the music; this does proper justice to Beethoven’s creative inspiration. Consistent with the approach that we’ll hear throughout the set, the orchestral sound in the Rondo finale is big and full. However, that doesn’t prevent the impish nature of the music from coming out; there’s plenty of life in the music-making. This reading of the finale is not as light-hearted and playful as some I’ve heard but it’s still very good.

While I admire the B flat concerto, I must say that, as a work, I enjoy its C major predecessor even more. Here, the first movement is presented firmly but though there’s satisfying weight in the orchestral sound I don’t find the performance heavy. I also like the grace that Klemperer achieves in the second subject. Barenboim’s playing is elegant and, particularly in the development section, inventive. He plays his own cadenza; it’s a very good discussion and elaboration of the thematic material but it is also quite substantial and I wondered if Klemperer, waiting to bring the orchestra back in, recollected his soloist’s ‘Yiddishe Cadenza’ quip from a few months earlier. I love Barenboim’s delicate musing in the opening bars of the Largo. What follows is expansively lyrical; more than that, pianist and conductor make it into a profound meditation. Barenboim is very poetic and his poetry is matched by the New Philharmonia’s principal clarinet, especially in his solo a few bars from the end. His colleagues in the NPO string section invest their contributions with pleasing depth of tone and they’re very sensitive to dynamic shading – as does the NPO throughout this set. The Rondo finale finds Barenboim displaying dexterity a-plenty while there’s bluff humour from the rostrum. I’ve heard more witty and mercurial accounts of this movement but, even so, I enjoyed this rendition very much.

The C minor concerto is the one where Beethoven takes the concerto form to a new level. Klemperer clearly recognises this and there’s a greater seriousness in the way he approaches the work. His pacing for the first movement is very steady – some may well feel that it’s too steady; you almost feel that the pulse is 4/4 rather than 2/2. I must admit that the first time I listened I felt the tempo was much too slow but over the course of the movement – and on subsequent hearings – Klemperer at least partially convinced me (though I wouldn’t necessarily want to hear the music unfolded this way every time). The long orchestral opening here becomes a big statement and when the piano enters Barenboim matches this mood, though that doesn’t preclude him from treating us to a good deal of graceful or sparkling playing over the movement’s course. The orchestral sound is trademark Klemperer with full, but not oppressive, tone in the strings and good woodwind cut-through. At the beginning of the Largo time seems almost to stand still as Barenboim plays his opening solo; he appears to be communing with himself. The movement is played and conducted in a very spacious fashion; listening to it is a profound experience. Just before the end there’s a little cadenza which is marked sempre con gran espressione and in Barenboim’s hands that’s exactly how the passage comes across; in truth, though, the entire movement has been delivered in that manner, both by him and by the orchestra. The concluding Rondo is taken at quite a steady pace by comparison with what we often hear nowadays. To me, however, the speed seems sensible and the music’s cheerful character is not inhibited. The final Presto is joyful and I love the poise with which Barenboim handles the lead into that last section from the little cadenza which precedes it. This is an impressive account of the concerto.

The Fourth has long been my favourite among the five concertos; indeed, it was the first to which I listened after receiving this set. The first movement is well-suited to the Barenboim/Klemperer approach; Klemperer’s way with the long orchestral introduction is at once magisterial and lyrical. Some may find the pace on the stately side; not me! I like breadth and a degree of weight in this movement and Klemperer provides this. In fact, his basic speed is not dissimilar to that adopted in one of my longtime favourite versions; the one made by Emil Gilels with the Philharmonia and Leopold Ludwig in 1957 (review). As for Barenboim, he is masterly in the way he plays the movement; his pianism strikes me as well-nigh ideal. He gives us Beethoven’s own cadenzas in the first and third movements; in the first movement he selects the first and longer of the two cadenzas, which he delivers with flair and imagination. I enjoyed this traversal of the first movement very much indeed. The first few minutes of the Andante con moto pits the gravitas and weighty sonority of the New Philharmonia’s strings against the delicate poetry of Barenboim. Eventually, he calms the orchestra into playing with a withdrawn pianissimo and the last couple of minutes have a special atmosphere. The Rondo finale receives an excellent performance. The concluding Presto section brings to an end a performance of the Fourth concerto which I admired.

The ’Emperor’ is the grandest of all the concertos and therefore, in some ways, the best suited to Klemperer’s conception of Beethoven. The opening of the first movement is made hugely imposing by both conductor and soloist. The long orchestral tutti that follows is taken at a steady pace and the performance has much grandeur; this is unashamedly ‘big band’ Beethoven. Barenboim plays the movement marvellously; he captures the heroic aspect of the writing but, in addition, he’s acutely responsive to the many subtle nuances. Overall, Klemperer and Barenboim present us with a grand conception of the movement, which pianist and orchestra execute extremely well. The second movement has genuine nobility here. I greatly admired Barenboim’s poetic touch, in which a wonderful use of rubato is a key factor. There’s genuine sensitivity in the solo playing and the members of the New Philharmonia match that. The finale is just a bit too steady for my liking; for all the felicitousness with which Barenboim plays the performance overall is rather too serious. This is, in many ways, a remarkable account of the ‘Emperor’ but it’s not a performance for every day.

For good measure, Barenboim and Klemperer added the Choral Fantasia to the set. What an odd work this is! It opens with an extended piano solo which in Barenboim’s hands, has the necessary feel of an improvisation. Then, when the orchestra joins the proceedings there’s a march episode. There follows what is in essence a theme and variations to which these performers give the flavour of a serenade. Eventually, vocal soloists and the choir join in, singing a pretty fulsome text, the authorship of which is uncertain. It’s an intriguing work, even if it isn’t top-drawer Beethoven. I enjoyed this performance.

This cycle of the Beethoven concertos won’t suit everyone. Whilst I think there will be general enthusiasm for the wonderful pianism of Daniel Barenboim, I can understand that not all will feel Otto Klemperer’s conducting is ideal. It is true that often the speeds adopted are on the broad side and the orchestral sound is often weighty but I can honestly say that I never found the sound of the orchestra to be excessively heavy – and I do like the firm bass foundation that Klemperer obtains. The New Philharmonia plays marvellously for him. As for the speeds, some of them are unquestionably on the stately side but I can only refer back to the point I made at the beginning of this review; maybe our ears have become over-accustomed to lithe and swift Beethoven. No one would ever accuse Klemperer of being HIP in his approach, yet his way with the music and the depth of his experience in conducting it by the time he made these recordings brings its own rewards. In the booklet Richard Osborne quotes Daniel Barenboim thus: ‘He [Klemperer] approached the essence of what he wanted directly and without hesitation. He was not interested in sound as such but in correctness of execution of tempo, dynamics, and orchestral balances, over which he took immense care.’ Listening to these performances that seems to me to be self-evident. At the start of this review, I referenced the age gap of some 57 years between pianist and conductor. By the time I’d finished evaluating their Beethoven collaborations I came to the conclusion that one of the joys of this set is the extent to which they bridged that gap successfully in a very genuine musical partnership.

I made a good number of spot comparisons between this new SACD remastering and the 2006 remastered CD set. To ensure a level playing field, I used the same Marantz universal player throughout and I made no adjustments to the system controls. I’ll just give a few examples here but they are representative, I think. On CD the opening of the First concerto was presented in pleasing sound; I noted a full bass and good definition. There was a degree of brightness to the sound, though not excessively so. When I played the same passage on SACD the sound was somewhat richer and fuller, though the brightness in the treble had not been sacrificed. The bass was quite a bit stronger than was the case on the CD, especially when the orchestra was playing loudly. The sound of the piano seemed to me to be a bit rounder on SACD. In the Rondo of the Second concerto the piano had more presence on SACD and I also noted a bit more space round the overall sound. At the start of the slow movement of the Fourth concerto the strings had good weight but the SACD offered more tonal depth in the same passage. Finally, it seemed to me that the grand rhetoric at the start of the ‘Emperor’ had more impact and depth of tone on SACD as compared with the CD.

As I hope the above paragraph has demonstrated, the SACD remastering does represent an advance on the CD, though I wouldn’t suggest that the advance is as significant as Decca recently achieved in remastering the Solti Ring cycle on SACD. I think that if you already have the CD incarnation of these Beethoven performances the differences are not sufficiently great that you should trade up. On the other hand, if you’re coming new to this cycle then the SACD is definitely the option to go for. Whichever version you listen to, the original recordings by producer Suvi Raj Grubb and engineer Robert Gooch were excellent and have come up very well in these remasterings. In passing, I recall reviewing in 2023 a remastered box set of Klemperer’s Mahler recordings for EMI. I wonder why Warner didn’t give those recordings the SACD treatment.

These Barenboim/Klemperer performances don’t constitute, I think, a top recommendation for the Beethoven piano concertos. However, this set is intriguing and repays close study. It has many rewards and contains a great deal to admire. It’s a justly famous collection of performances and this latest remastering serves it well.

John Quinn

Previous reviews (CD releases): David R Dunsmore ~ Simon Thompson

Buying this recording via the link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.