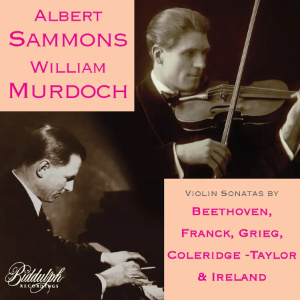

Albert Sammons and William Murdoch

The complete sonata recordings (1916-17)

Contents listed after review

Albert Sammons (violin), William Murdoch (piano)

rec. 1916-17, London

Biddulph 85055-2 [73]

Albert Sammons won national fame when, during the early months of the First World War, he performed Elgar’s Violin Concerto. He had just relinquished leadership of Beecham’s eponymous Symphony Orchestra, was first violinist of the London String Quartet, and Columbia was eager to engage him in recordings. In March 1916 they recorded him in a truncated version of the Elgar Concerto (review) and in June that year they dipped toes into the sonata repertoire by recording him and his new sonata partner, William Murdoch, in truncations of the first two movements of the Franck and Grieg C minor sonatas. Sammons and Murdoch’s acoustic sonata recordings of 1916-17 are the focus of this fascinating retrieval from Biddulph.

Both these sonatas are what-ifs of Sammons’s discography. Murdoch later recorded the whole of the Franck sonata with Arthur Catterall, not with Sammons, who had by then defected to the rival Vocalion company. Neither man returned to the Grieg, though they did make a memorable recording of the Second Sonata. Sammons had often heard his early inspiration, Eugène Ysaÿe, play the Franck and Sammons’ direct, incisive and virtuosic playing is an index of his affiliations with the Franco-Belgian repertoire – he frequently played the Lekeu and was devoted to it – and both men are equally effective in the Grieg, which was recorded at the same time as the Franck.

A single 12” disc offering two movements from a sonata was not wholly satisfactory, even at a time when truncations were standard, so the following year Columbia offered their star British violinist more comprehensive fare. They began in March 1917 with a truncated Kreutzer Sonata which took just under 14 minutes. When he and Murdoch made their electrical recording of it, they took 31. As ever, Sammons’ direct, unmawkish playing offers both technical security and lofty expression, and his accompanying figures are well-balanced. The central movement occupied two sides and fortunately, its variations offered a natural turnover point. Murdoch is well recorded, too, and there’s no hint of the ‘banjo’ tone of the piano, so often complained about in recordings of the time. Later in the year, they recorded the Spring Sonata where Sammons’ accompanying figures are over-recorded in relation to the piano, an ever-present danger in acoustic recording, but where his singing tone can be savoured, allied to a plentiful, but very precise, employment of portamenti – significantly more than he essays in the Kreutzer. Unlike other better-remembered duos, Sammons and Murdoch don’t downplay the rhythmic hi-jinks of the Scherzo.

The two most historically important recordings are the Coleridge-Taylor and Ireland Sonatas because Sammons was so closely identified with them, particularly the latter. They were recorded in conjunction with public performances of the works – in Ireland’s case, it was premièred on 6 March 1917 and recorded the following day. Though Sammons was to make a complete recording with the composer in 1930 it wasn’t issued for decades, finally appearing on a Dutton CD (review), and this truncated version preserves half the work. Nevertheless, it gives a strong indication of the effect this war-saturated work must have had on audiences of the time. By contrast, the Coleridge-Taylor Sonata is an early work edited and premièred by Sammons. It is drenched in folkloric and lighter elements, grist to Sammons’ mill as an erstwhile café and restaurant fiddler. This is the most tricky of the 78s to find and couldn’t have sold that well but that’s no fault of the performers, as they play it with stylistic assurance and stylish phrasing. Sammons’s cantilena in the finale is a thing of wonder, as is the way he draws melodic distinction from the pizzicati in the central movement. He is quite sparing in portamento use here.

I appreciate that those who collect acoustic recordings are a somewhat obsessive sub-set of classical collectors. However, if you’ve read this far, it’s not because of my immortal prose, it’s because these recordings presumably interest you. So, it’s worth noting that this is, to my knowledge, the first time these recordings have been reissued since they were first released nearly 110 years ago. The copies have been splendidly transferred and mastered – Raymond Glaspole transferred his own discs and Rick Torres did the digital mastering – presentation is very attractive, and the booklet notes were written by the present writer.

Jonathan Woolf

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents:

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Violin Sonata No 5 in F, Op 24 Spring (1800-01)

Violin Sonata No 9 in A, Op 47 Kreutzer (1802-03)

César Franck (1822-1890)

Violin Sonata in A major (1886); Movements 1 and 2

Edvard Grieg (1843-1907)

Violin Sonata No 3 in C minor, Op 45 (1886); Movements 1 and 2

Samuel Coleridge-Taylor (1875-1912)

Violin Sonata in D minor, Op 28 (1897)

John Ireland (1879-1962)

Violin Sonata No 2 in A minor (1915-1917)