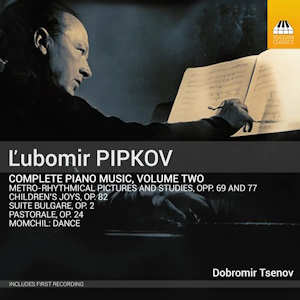

Ľubomir Pipkov (1904-74)

Complete Piano Music Volume Two

Suite Bulgare, Op.2 (1928)

Pastorale, Op.24 (1944)

Momchil, Op.28: Dance (1939-43 transcr. 1948)

Metro-rhythmical Pictures and Studies, Op.69 (1969)

Metro-rhythmical Pictures and Studies, Op.77 (1972)

Children’s Joys, Op.82 (1973; unfinished)

Dobromir Tsenov (piano)

rec. 2024, Studio 1 Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, UK

First recording (op. 82)

Toccata Classics TOCC0744 [76]

It doesn’t seem possible that it was two years ago that I reviewed Volume One of the piano music of Ľubomir Pipkov and I am thrilled to have Volume Two in my hands now. I have eagerly awaited it and it certainly doesn’t disappoint. Once again, pianist Dobromir Tsenov’s booklet notes are really helpful as well as insightful in charting Pipkov’s development. In common with so many composers from countries who did not have a distinctive and recognisable style of classical music in the early years of the twentieth century, Pipkov felt a duty to make his contribution towards creating one. Around the same time as Bartók and Aaron Copland were doing their bit in establishing a distinctive Hungarian and American sound respectively, a number of Bulgarian composers were trying to do the same. As Tsenov explains, they were defined as being part of the ‘second generation’ of Bulgarian composers ‘whose prolific output contributed to the development of professional music in his native country’. Bulgarian composers had an easier job, as did Bartók, than did Copland, due to the rich vein of folk music that existed in their countries and which is still an important part of their heritage and which continues to be widely popular.

Pipkov’s early Op.2 set, entitled Suite Bulgare, from 1928, brings those rhythms to the fore; they are perhaps most pronounced in the third marked Allegro ritmico and the sixth, Allegro molto. This work which he composed in Paris where he was a student, led his teacher, Paul Dukas, to comment that ‘Pipkov has found his style’. The suite demonstrates how well he was able to incorporate folksongs into music that would be acceptable in concert halls.

Pastorale, composed in 1944, is a gently lyrical piece but the influence of folk elements is still there and easily identified. Reflective and nostalgic by turns, it shows how the very specific Bulgarian nature is not only apparent in rumbustious dances but also in serious, not to say sad, occasions. The next piece is a dance Pipkov transcribed for piano from one of his three operas, Momchil, which was first staged in 1948. As Tsenov writes, it ‘features Pipkov’s favourite intervals: parallel octaves, fourths and fifths’. Bulgarian rhythms are so infectious; the listener will always find pleasure in them.

Then comes the first set of two Metro-rhythmical Pictures and Studies, consisting of twelve short pieces, each exploring a different time signature. I have to admit that the explanation of the workings of the pieces was beyond my understanding so I cannot convey them to the reader. However, the original title was Children’s Album so you can rest assured that while the ‘musical mathematics’ might be complex, the music itself is not, for anything that involves traditional folk rhythms and melodies will always be immediately understandable and enjoyable. Each of these short pieces has a title such as Shepherd and pigeons or The Cranes are Flying Away and while most are upbeat joyous tunes others convey longing, or melancholia. Although they are all enjoyable, I always love the overtly joyous ones that recall national dances, so highlights for me were Rachenitsa, Horo and Fairytale. However, what lifts Pipkov’s music to another level from pure folk-inspired works is his inventiveness, so that while the root of the music is easily recognisable, in Pipkov’s hands it is transformed into a genuinely original piece. His overall credo was to take a creative seed and plant it in the ‘soil’ of folklore’, thus forging a national compositional style. Bulgarian folk music has existed for centuries so composers like Pipkov had masses of material to use as a basis to forge such a style, while as I mentioned before. composers like Copland had a far more difficult job, since the history of America was so short so that his cycle Old American Songs had its roots in what any of us in Europe or further east would call ‘modern history’. Though I’m sure there exists rhythms and melodies that native American tribes have in their history I can’t say I know anything of them.

Published jointly with Pipkov’s Op.69 set was his Op.77 set of Metro-rhythmical Pictures and Studies which followed three years later. This set of six pieces consists of longer examples, each also bearing a title. The first, Study No.2 is more experimental though the rhythm is still recognisably Bulgarian. What fascinates me is how much work goes into the briefest of pieces; take the third Study No.3. I quote from Dobromir Tsenov’s notes ‘…it sounds charmingly chaotic. The piece features a variety of tempo-markings (like Andantino cantabile, Più vivo, Andante cantabile, Allegro, Meno mosso), sharp dynamic contrasts (from fff to ppp) and time signatures…the left hand moving in a sequence of six equal crotchets (2+2+2+2+2+2), which attests to his modern thinking. All these characteristics make No.3 one of the most interesting pieces of the set’. All this complex writing is incorporated within a mere 3:26.

The final work on the disc is Pipkov’s last and, regrettably, unfinished Children’s Joys which was projected to contain 23 miniatures of which he managed to complete fourteen. These were intended to be played by pianists at the beginning of their pianistic journey and while they may not place such demands on the player as others on the disc, they nevertheless still show Pipkov’s unique style. These are disarmingly charming miniatures, none lasting much over 90 seconds and many much shorter but Pipkov can express a great deal in such a tiny time frame, a good example of which is Little Radka with a Headscarf which is a mere 24 bars and 39 seconds long.

Whether there are any more of Pipkov’s works for piano to be recorded I don’t know but I shall be eager to hear them if so. Sometimes dissecting pieces to impart an impression of what the listener could expect to hear is somehow superfluous, though obviously for the expert there is an academic interest and Dobromir Tsenov’s insightful notes fulfil that thoroughly. For me, though, it’s all about how happy a listener I am made to feel and this composer delivers that in every single piece. Ľubomir Pipkov achieved his aim of helping to create a recognisably Bulgarian sound in classical music and as such will always occupy a special place in the country’s musical heritage. The music is thoroughly enjoyable and Tsenov’s playing is crystalline in its clarity; he meets the obvious challenges with aplomb. I would be really interested to hear him tackle anything; I can imagine his Bartók and Janaček would be masterful.

Steve Arloff

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free