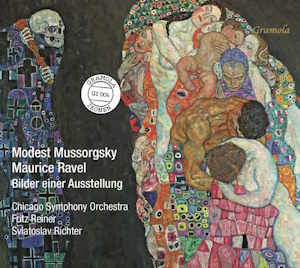

Modest Mussorgsky (1830-1881)

Pictures at an Exhibition for piano (1874)

Pictures at an Exhibition (orch. Ravel, 1929)

Sviatoslav Richter (piano)

Chicago Symphony Orchestra/Fritz Reiner

rec. 1957, Chicago (orchestral); 1958, Moscow (piano)

Gramola 92004 [64]

Here are two classic accounts of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, coupled together. Reiner’s recording of the Ravel orchestration with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra dates from 1957 and Richter’s of the piano original from 1958. I should say straightaway that the recording quality of each of them, while not that of today, is very acceptable, and you need no special toleration to enjoy these performances.

Reiner’s performance of the Ravel version combines great precision in the playing with great drive. This is the opposite of the kind of routine playthrough I have heard too often. For a start, the Promenades are nicely differentiated, with Ravel’s varying orchestrations well observed. In Gnomus he uses the written pauses to good effect, emphasizing the abruptness of the main figure. Here and elsewhere you can also hear Ravel’s precisely notated percussion parts, in this piece requiring tambourine, cymbals and bass drum. The chording of the woodwind interjections is exact in both intonation and tempo. The rumblings near the end are powerfully done and the final scurry is both fast and accurate. In Il Vecchio Castello the saxophone has an unusually pure tone, with no vibrato at all. Reiner keeps this piece moving – it can seem overlong, but not here – and the variations in the tune and the orchestration keep it alive. (Ravel adds a bar in this piece to Mussorgsky’s original.)

In Tuileries, as also in the Ballet des Poussins and Limoges I admired the nimble, accurate and witty playing of the woodwind. In Bydlo Reiner follows Ravel’s direction to begin pianissimo – the piano original begins fortissimo – as the ox cart lumbers into view as expressed by a highlying solo for the tuba. The climax is weighty but you can still hear the harp; both Reiner and the balance engineers can take credit for that. In Samuel Goldenberg and Schmuyle the first trumpet deserves an award for his rapid and precise staccato playing, and, when the second trumpet joins him an octave below, their unanimity is perfect. In Catacombae the brass playing is powerful but controlled and in Cum Mortuis again I noted that the important harp line was clearly audible. In La Cabane sur des Pattes de Poule (Baba Yaga) the outer sections had a rhythmic drive worthy of Stravinsky, while the middle section, with flutes, one bassoon and double basses, was suitably sinister. The final Great Gate can get ponderous but Reiner keeps it moving and carefully grades the increasingly rich orchestral texture. There is no wonder that this is a classic performance.

Richter’s solo version is not the 1958 live Sofia account, which I have not heard but which is highly esteemed by Richter fans, despite apparently very poor sound. This is a studio account made in Moscow in the same year. I should add that Richter plays the score as written, as opposed to Horowitz and some others who revise Mussorgsky’s occasionally ungainly piano writing, though not the substance, to make it more pianistic. I have no objections in principle to this, but I can say that Richter makes the solo piano version mostly convincing – though those passages which rely on tremolos, and some of the chordal ones, sound as if it is the piano version which is the transcription and Ravel’s orchestration the original.

Richter makes the Promenades urgent rather than leisurely, a good idea since they have a good deal of repetition – Ravel’s orchestration greatly adds to their appeal, and he also omitted the last of them. Richter also scrupulously follows Mussorgsky’s direction that each Promenade should lead directly into the following number without a pause. Gnomus is clearly articulated and vivid. In Il Vecchio Castello Richter nicely shapes the bass line and takes care to mould the melody so that its windings and repetitions charm and do not weary the ear. Tuileries is elegant and nimble; I noted that Richter speeded up a bit in the middle section. Bydlo, as I noted above, here begins fortissimo and then the climax is marked con tutta forza, making a thunderous roar. The Ballet de Poussins is very pianistically written and so rather different from the orchestral version. Samuel Goldenburg and Schmuyle is nicely done, though once one has heard Ravel’s muted trumpet it is hard to get that out of one’s ears. At this point we have the Promenade which Ravel excised. Limoges is another very pianistic number, though very tricky to play; Richter surmounts its challenges with aplomb, with a real helter skelter ending. In Catacombae the way that piano chords, particularly loud ones, begin with great force then rapidly die away, is part of the conception of the pieces, and quite different from Ravel’s use of contrasting brass groups. Cum mortuis is one of the pieces which rely on tremolo, which makes it sound like an arrangement. La Cabane sur des Pattes de Poule (Baba Yaga) is suitably ferocious in the outer sections, while the middle section again relies on tremolo. In the final Great Gate Richter carefully grades the increasing elaboration of the writing and keeps the final section, marked meno mosso, moving and well- shaped. It is a formidable performance and one which makes the best case for the piano original.

Mussorgsky fans will want more modern recordings of both versions of the Pictures, but they should not overlook these two classic accounts, conveniently coupled.

Stephen Barber

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free