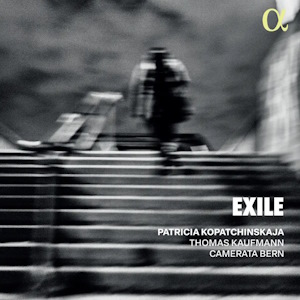

Exile

Thomas Kaufmann (cello)

Camerata Bern/Patricia Kopatchinskaja (violin)

rec. 2024, Kirche Diaconis, Bern, Switzerland

Alpha Classics 1110 [74]

Feeling or being forced to become an exile from one’s homeland is a bitter experience appreciated only by those who have gone through it. The choice of repertoire on this disc is an interesting one, as for two of the composers the link with exile is a tenuous one (Schubert and Wyschnegradsky) and the two folk works serve only to show the extent to which music is so rooted in a particular culture. That said the disc is nevertheless fascinating. The opening piece Kugikly is the name for Russian and Ukrainian panpipes as well as the piece itself. It was amazing to read that excavations in Ukraine have found examples dating back 5,000 years. They are also to be found in many cultures, and there is an implication that they may have originated in Africa among the pygmies and yet are also to be found elsewhere in the world, particularly as far away as Peru and other countries of Latin America. The instrument therefore is itself an exile from its original home. Jonathan Keren’s imaginative arrangement by ear of this traditional melody for string ensemble preserves the folkloric element and its very infectious and affecting nature.

Alfred Schnittke didn’t become an exile from his native Soviet homeland until the country was on the cusp of ceasing to be a communist country. Nevertheless, it sounds as if the work here presented, written in 1978, has elements within it that suggest a longing for his home as if he was already an exile. His Sonata for cello and piano begins with the cello alone before the other strings enter. The writing is spare and the cello sings out a heartfelt and plaintive tune that sounds both questioning and anguished, before the strings manage to restore a measure of calm just as the movement comes to a close. The Presto begins with the cello playing eighth-notes fast and furiously in an urgent mood, its anguished nature reaching a frantic and disturbed level it seems unable to shake off, the strings mirroring this heightened level of anxiety and it ends suddenly. The cellist is tested hugely for there is no let-up in the demand that he play as fast as possible, making it a jaw-dropping experience. The Largo is a return to the work’s opening, and as Benjamin Herzog writes in the notes, it appears the music now knows the answers to the questions it posed. The music certainly sounds as if it has come to terms with the situation. I don’t know the work in its original form but am now eager to hear how different it sounds to this extremely powerful version in which the strings stand in for the piano, though with two minutes to go before the end, the arranger interestingly introduces a harpsichord into the mix for a scant number of notes. I would be interested to hear the arranger’s thinking on that choice.

Patricia Kopatchinskaja joins violinist Vlad Popescu to sing the traditional Moldovan folk song Cuckoo with grey feather, both being of Moldovan or Romanian origin. The eerie nature of the tune is very effective, with Patricia’s voice high above Popescu’s, and it sounds as if a pipe (kugikly?) is playing against the cello drone.

Andrzej Panufnik left what he found to be the suffocating nature of Communist Poland as early as 1954, becoming a British citizen. He was knighted for services to music in 1991, shortly before his death. His Concerto for violin and strings was commissioned by Yehudi Menuhin and is a highly virtuosic piece, though without any suggestion of being showy. At the start, the violin alone plays for a minute before the strings enter. The movement suggests a degree of restlessness and anxiety despite the sweet tones while the second is at ease with itself and there are hints of Polish folk music woven into the fabric of this gently unfolding Adagio which comes to a quiet close. The finale marked Vivace sets of at an excitingly energetic pace which it maintains throughout it six-minute length apart from a degree of slowing down a minute before the end as the violin seems to play with the listener for twenty seconds or so before resuming its energy to close.

I have to say I find unconvincing the ‘argument’ for including the arrangement made by Patricia Kopatchinskaja of the third of Schubert’s 5 Minuets and 6 Trios for string quartet, D89, as Schubert was no exile – but he was a permanent, ever-restless wanderer, and her arrangement is highly effective. However, given that throughout history there are hundreds of examples of composers who were exiled either by choice or enforcement, Schubert’s inclusion on this disc seems to stretch the scope of the subject unnecessarily.

If I understand the connection of Ivan Wyschnegradsky with exile, once again I find it strange that he is included since he is said to have been a supporter of the ideals of the Russian Revolution. The fact that he moved with his family to Paris in 1920 is not explained, though there is a suggestion that his interest in dissonance using quarter tone pianos would have been regarded with suspicion in the Soviet Union, though not, I’d have thought in those early days when art there was experiencing much experimentation. Again, I find it is stretching things to imply he was effectively an exile within himself, because there were so few others trying to forge the atonal path. That said, his second string quartet must have seemed ultra ‘modern’ when it was composed in 1931, whereas today, almost a hundred years later, it doesn’t have ‘the shock of the new’ to anything like the same extent. I find Benjamin Herzog’s description that Wyschnegradsky’s use of quarter tones ‘can give a piece a kind of saucy charm’ to be spot on and it makes it enjoyable rather than purely experimental.

The final work on the disc, Exil!, is by virtuoso violinist Eugène Ysaÿe, whose pieces are so often played by violinists. He fled Belgium in the First world War when German troops marched in to occupy his country. First, he went to England but ended up in the US. His eight minute composition is for four violins and four violas, and is full of palpable feelings of homesickness. Its heart-wrenching melancholy certainly manages to put into music those powerful emotions he and so many other exiles feel when forced to flee their native lands.

Despite the nit picking some might feel I have expressed, I very much enjoyed the disc and the playing by both soloists, and the Camerata Bern is faultless and the sound is crisp. Patricia Kopatchinskaja is a thoroughly committed artist of prodigious talent and anything she chooses to play is bound to give pleasure.

Steve Arloff

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Traditional

Kugikly for violin and Ukrainian & Russian panpipes

Transcribed and arranged for string ensemble by Jonathan Keren

Alfred Schnittke (1934-1998)

Sonata for cello and piano No.1

Version for cello, strings and harpsichord by Martin Merker (2020)

Traditional (Moldovan folklore)

Cucuşor cu pană sură (Cuckoo with grey feather)

Andrzej Panufnik (1914-1991)

Concerto for violin and strings

Franz Schubert (1797-1828)

No.3 of the 5 Minuets and 6 Trios for string quartet, D89

Arranged for string ensemble by Patricia Kopatchinskaja

Ivan Wyschnegradsky (1893-1979)

String Quartet No.2, Op.18

Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931)

Exil! – Poème symphonique for high strings, Op.25

Note: Patricia Kopatchinskaja is also the singer on Cuckoo with grey feather, with Vlad Popescu