Giacomo Puccini (1858-1924)

La Bohème, Opera in 4 Acts (1893-95)

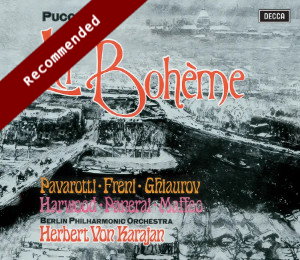

Mimi, Mirella Frei (soprano); Rodolfo, Luciano Pavarotti (tenor); Musetta, Elizabeth Harwood (soprano); Marcello, Rolando Panerai (baritone); Schaunard, Gianni Maffeo (baritone); Colline, Nicolai Ghiaurov (bass)

Schöneberger Sängerknaben; Chor des Deutschen Oper, Berlin

Berliner Philharmoniker / Herbert von Karajan

rec. 9-13 October 1972, Jesus- Christus-Kirche, Berlin

Italian libretto and English, French & German translations included

Decca 487 0503 SACD [2 discs: 110]

Over the last couple of years Decca have taken a few of the most famous recordings in their catalogue – Solti’s Ring cycle and Britten’s own recording of War Requiem – and have reissued them in a de-luxe format. The most compelling feature of these reissues has been the remastering of the original tapes and the presentation of the recordings on SACDs. The latest recording to benefit from this treatment is Herbert von Karajan’s justly famous 1972 recording of La Bohème.

Decca first issued this recording on LP in 1973. I believe its initial CD release came in 1987; that’s the version I have in my collection. In 2008, to mark the 150th anniversary of Puccini’s birth, Decca released a CD version in 96kHz-24-bit remastered sound. My colleague Göran Forsling wrote a review of that release. As I’ve previously done with Decca’s other SACD remasterings, I will make some comparisons between the new incarnation of the recording and the CD, though I’m conscious that I will be using the 1987 iteration; I don’t know the extent to which the 2008 remastering represented an advance on 1987.

But before considering the audio side of things I should talk about the performance. Many readers will be familiar with this account of Puccini’s enduringly popular opera and won’t need me to extol its virtues. However, if you haven’t heard Karajan and his team in this opera before I can assure you it’s a very special experience. The cast that Decca assembled was magnificent in every way. I had forgotten that Luciano Pavarotti came to the part of Rodolfo just a matter of weeks after he had taken part in another Puccini recording for the ages. In August 1972 he had been in London to sing Calaf in Decca’s recording of Turandot conducted by Zubin Mehta. My colleague Lee Denham selected it as one of his top recommendations when he compiled an exhaustive survey of recordings of the opera in 2023 and he was loud in his praises of all aspects of the recording. One comment particularly caught my eye. Of Pavarotti he wrote this: “As always, his combination of boyish enthusiasm and charm, allied to the sheer panache of his singing, papers over the darker and more complex aspects of the character in a way that he would also do with other roles such as Lieutenant Pinkerton and the Duke of Mantua, to produce a nonetheless thrilling reading.” It may be significant that Lee omitted Rodolfo from his list of “other roles”; arguably, there’s a little less complexity of character to the part of Rodolfo. As Lee noted, Pavarotti was in magnificent voice for Mehta and he was no less thrilling for Karajan. (Incidentally, Nicolai Ghiaurov was also involved in the Mehta recording, singing the role of Timur, and I was glad to see that Lee was as impressed as I was by his contribution to Turandot.)

The sheer open-throated ardour of Pavarotti’s singing is well-nigh irresistible in this La Bohème. To hear his gleaming voice in ‘Che gelida manina’ is an unforgettable experience; the ease with which he spins the vocal line and the seemingly effortless high notes demonstrate what fine form he was in at this point in his career (he celebrated his 37th birthday on the penultimate day of the recording sessions). He’s no less impressive in ‘O soave fanciulla’. As the opera approaches its tragic dénouement, he makes a memorable contribution in the final exchanges between Rodolfo and the dying Mimi. Earlier, though, he plays his full part in the carefree exchanges between Rodolfo and his three garret friends.

On the cover of the box which houses this set Decca highlight the names of Pavarotti and Karajan but in my opinion a third name should be there. That the set is such a triumph is as much due to Mirella Freni as to anyone else. Quite simply, she is an outstanding Mimi. She embraces all aspects of the character, beginning with shyness (‘Mi chiamano Mimi’), moving through joy at finding love with Rodolfo to anguish in Act III when she explains to Marcello that her relationship with Rodolfo has hit the rocks. In the final Act her singing in her dying duet with Pavarotti would melt a heart of stone. Freni’s characterisation is completely involved and involving and, as we listen, her vocal acting draws us in to Mimi’s ultimately tragic situation. Yet all this is achieved without any histrionics, nor is beauty of singing and control of line ever sacrificed for dramatic effect. It’s a considerable bonus that there is an evident and genuine chemistry between Freni and Pavarotti; as Roger Pines reminds us in his excellent booklet essay, they were exact contemporaries, fellow Modenese and lifelong friends. I was greatly moved by Freni’s performance and admired her singing qua singing enormously.

The other singers are ideally cast. Elizabeth Harwood was an inspired choice for the role of Musetta. She’s completely convincing as the coquettish flirt in Act II as she twists Alcindoro round her little finger; later on, though, the greater depths of Musetta’s character are portrayed by Harwood as lover of Marcello and, at the end, supportive friend of Mimi. Her singing is as admirable as her characterisation. Rolando Panerai is a splendid, stalwart Marcello while Gianni Maffeo (Schaunard) and Nicolai Ghiaurov (Colline) complete the quartet of bohemian friends. As the four male characters josh each other at the start of Act I and again as Act IV opens, you get a real sense of camaraderie; the singers strike sparks off each other. And I must not forget to mention Ghiaurov’s moving rendition of Colline’s sorrowful solo in Act IV (‘Vecchia zimarra, senti’). Among the smaller roles Michel Sénéchal has to assume not one but two put-upon characters: Benoît and Alcindoro. He takes both of these parts most convincingly.

There’s a short but fascinating note in the booklet by James Lock, one of the three Decca engineers who brought about this recording (the others were Gordon Parry and Colin Moorfoot and the producers were Ray Minshull and James Mallinson; a vintage Decca team). Lock reminds us that the Berliner Philharmoniker was not an opera orchestra, but he says that Karajan rehearsed them in minute detail for this assignment. My goodness, it shows. The playing is simply fabulous. Whenever it’s called for, the playing has power and impact but what impresses me time and again is the sheer refinement of the playing in the quieter, tender moments. In particular, the sensitivity of the orchestra as Mimi expires has to be heard to be believed. The Decca engineering does full justice to this superb playing in a recording that is full-bodied yet also allows an abundance of detail to be heard. I should also say that the choral singing, both by the adult chorus and the ragazzi, is right on point at all times.

Karajan conducts magnificently. Under his direction there’s real dynamism and joie de vivre in such passages as the very opening of the opera and the teeming street scene outside the Café Momus in Act II. At times it might be argued that Karajan’s tempi are on the expansive side but I never had any sense that the pacing was too slow; rather, when the conductor opts for expansiveness it’s to allow his singers – and his orchestral players, too – to phrase expressively. Above all, you feel that Karajan is ‘with’ his singers at all times, guiding and directing them, of course, but also supporting them. It’s a masterly demonstration of the art of conducting.

This, then, is an unforgettable recording of La Bohème. But don’t just take my word for it. It’s time to summon expert witnesses in the shape of two colleagues, Ralph Moore and Göran Forsling, both of whom have undoubtedly heard far more versions of the opera than I have.

Ralph has compiled for MusicWeb many surveys of recordings of individual works, mostly operas. Recently, I was browsing through the index of these surveys and noticed that La Bohème was not among them. I wondered if our usually reliable indexing system might, for once, be at fault and I asked Ralph if there was such a survey hidden in plain sight on MusicWeb. His reply intrigued me: “The answer to that is very simple, John; it is in my “Untouchables” list as I cannot see how the Karajan recording – about to be reissued by Decca in a new remastering – can ever be bettered.” Göran reviewed the 2008 CD remastering of this recording. After a judicious weighing-up of several alternatives, including the famous de los Angeles/Björling/Beecham set (long a favourite of mine), he summed up the Karajan version thus: “This is one of the greatest opera recordings of all times.”

Having, I hope, established the very considerable artistic merits of this set it’s time to weigh up the audio side of things. It’s worth making one general point first. James Lock tells us that this project was Decca’s first opportunity to work with Karajan and the Berliner Philharmoniker in Berlin’s Jesus- Christus-Kirche, hitherto an exclusive preserve of Deutsche Grammophon. It can be difficult for a recording team to get to grips with a venue which is new to them. For instance, some critics have suggested that when Sir Simon Rattle began recording with the same orchestra at the time when he was still contracted to EMI their engineers struggled initially to get an optimum sound in the Philharmonie. By contrast, I think the present recording demonstrates that the Decca team got it right first time. In whichever incarnation you listen to this recording I think you’ll find it consistently successful. I’ve mentioned already the excellent way in which the orchestra is recorded. Equally, the singers’ voices are marvellously and truthfully captured by the microphones. Furthermore, the engineering convincingly conveys an aural image of a deep and wide opera house stage so that in the crowd scene in Act II you really get a sense of groups of characters stationed at various points in the sound stage.

I wanted to see how the CD sound measured up against the new remastering. For this purpose, I made several A/B comparisons between the 1987 CDs and the new SACDs, using the same Marantz player to audition both versions and making no changes to the system controls. Here are some examples of what I experienced. At the very start of the opera the sound on CD is bright – though not overbright. The voices are clearly heard; the singers are well balanced with each other and against the orchestra. The SACD sound is rather more vivid and there is more body to the orchestral sound in particular. I also noted a bit more warmth to the sound overall and that there’s more acoustic space around both the singers and the orchestra. Moving further into the Act, I was keen to compare ‘Che gelida manina’. Pavarotti’s voice makes a fine impression on CD; there’s just the right degree of natural edge to his tone and the microphones capture that as well as the wonderful gleaming sound he produces. On SACD the voice has even more presence.

The opening of Act II is an excellent point of comparison because one can hear the full ensemble in action. On CD both the sound and the performance come across as bright and vivacious. The hustle and bustle of the scene is very well conveyed and the recording team have ensured that the various elements of the ensemble are heard in good, realistic perspective, with some performers foregrounded and others obviously positioned towards the rear of the ‘stage’. The SACD definitely offers more presence and body and one’s sense of a deep and wide ‘stage’ is enhanced. The final specific comparison I’ll mention is the very end of the opera (tr 15 on the second SACD, beginning at ‘Oh Dio! Mimi!’). These closing minutes sound very well indeed on CD but on SACD the voices register with even more presence and you can really appreciate the silken playing of the orchestra. The listener feels particularly drawn into the sadness of the scene when listening to the SACDs and Pavarotti’s anguish when he realises that Mimi has expired is palpable.

It seems to me that the newly remastered sound on SACD offers an enhanced listening experience. If I’m honest, I’m not sure that the case for the SACD version is quite so compelling as was the case with the Ring or War Requiem but I think that this reflects the fact that those recordings were several years older than this recording of La Bohème – fourteen years older in the case of the 1958 Rheingold. I’m in no doubt that listening to the remastered version of La Bohème is a thrilling experience. Of course, one can’t overlook the issue of price. This new La Bohème is an expensive proposition in its SACD incarnation; in the UK, online retailers are currently quoting prices ranging between £101 and £109. I don’t know if a digital download will be available when the set is released on 22 November. If that’s the case then that may well be a significantly cheaper option. As an example, Presto Classical, a leading UK retailer, currently has the 2023 remastered version of War Requiem listed for £85 on SACD but if you opt for a download their prices range from £12.68 to £22.19 depending on which audio format you choose.

The documentation accompanying this set is very high quality. As was the case with the previous SACD sets of The Ring and War Requiem, the discs and documentation are housed in an LP-sized case. The hardback booklet, lavishly illustrated with session photographs, contains the libretto along with translations in English French and German. The accompanying essays are in English and German. There’s a very fine extended essay about the opera and this particular recording of it by Roger Pines and there are other contributions by James Lock, already referenced, by James Jolly (on Mirella Freni) and a short conversation between Pavarotti and Jon Tolansky. However, looking at the section of Göran Forsling’s review of the 2008 CD reissue in which he references the documentation, I suspect that at least some of this material has been recycled into the 2024 booklet. There is one essay which is definitely new: an appreciation of Pavarotti as a Puccini artist by the British tenor, Freddie De Tommaso.

This remastered version of La Bohème is a premium product but in life you get what you pay for. The sound on these SACDs is terrific, doing justice to the very special performance. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to describe this Karajan performance as a classic recording. Let me end with a heartfelt plea to Decca to give the SACD treatment to the other classic Puccini recording that they set down in 1972: the magnificent Sutherland/Pavarotti/Mehta account of Turandot. That’s just as deserving of optimum sound as is this wonderful La Bohème.

John Quinn

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Other cast

Benoît / Alcindoro, Michel Sénéchal (tenor); Parpignol, Gernot Pietsch (tenor); Doganiere, Hans-Dietrich Pohl (bass); Sergente dei doganieri, Hans-Dieter Appelt (bass)