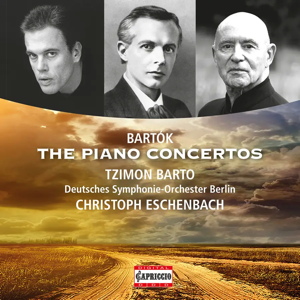

Béla Bartók (1881-1945)

Piano Concerto No. 1 (1926)

Piano Concerto No. 2 (1931)

Piano Concerto No. 3 (1945)

Tzimon Barto (piano), Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin/Christophe Eschenbach

rec. 2018/19, Jesus-Christus-Kirche, Dahlem & Philharmonie, Berlin, Germany

Capriccio C5537 [2 CDs: 88]

The soloist for whom Bartók composed his first piano concerto – written in the space of some four months in 1926 – was himself. The solo part is fiendishly difficult, but there are few passages that seem to be designed to show off the soloist’s skill: this concerto is neither a flamboyant showpiece nor a titanic battle between piano and orchestra. On the contrary, for much of the first movement, in particular, the piano is part of the ensemble, prominent only because of its different sound. There is much writing in octaves and many passages where the hands mirror each other. The slow movement is based on three repeated notes, much of the material given to the piano over ticking percussion; the strings are completely silent. The finale is wild, its lyrical passages few and far between. Rhythmic drive, rather than thematic content, dominates the whole work, those rhythms highly complex and with frequent changes of metre. The music is intensely chromatic and dissonant: listeners who know Bartók through his later works, the Concerto for Orchestra, for instance, may well find it hard going. This is, though, an ideal performance for those new to the work. With but little help from the composer, Tzimon Barto introduces significant variety of touch and tone to the solo part. His virtuosity is never in doubt, and the orchestra sticks to him like glue, no mean feat. Of the two performances I have available for comparison, that by the great Géza Anda on DG with Ferenc Fricsay and recorded in 1960 is similar in that the pianist allows glimpses of light to penetrate what can seem like a relentless onslaught. Jenő Jandó’s playing (Naxos, 1994) is less varied, more violent throughout, rendering the work less accessible. The orchestral playing in this new issue is superior to both, as is the recorded sound.

Much the same might be said when comparing the three pianists in the second concerto. Here, though, I can also cite a fourth performance, by André Watts and Bernstein, originally recorded on CBS and, as far as I know, unavailable on CD. They make the work more fun than any of the other three, with the word ‘fun’ carefully chosen, though it is remains a relative term. The work opens, after an initial flourish from the soloist, with just what we might find missing in the first concerto, a tune, albeit short, given out by the trumpet. The strings, once again, do not play at all in this movement, but the scoring is so resourceful that we do not miss them. The second movement, on the other hand, begins with the strings, muted throughout, whose calm parallel chords are in great contrast to the preceding turbulence. This movement is an example of what has come to be called Bartók’s ‘night music’ manner, examples of which can be found in several of his works. Brass dominate again in the exhilarating finale, with the opening theme brought back into service. The energy here is irresistible, plus a very few, rather beautiful, lyrical episodes. The work rushes to a breathless and, in the right hands – such as here, but even more so with André Watts – entertaining close.

In a long booklet essay that is packed with information – though we may not agree with every point he makes – Jens F. Laurson traces the composer’s life in detail. He reminds us that Bartók’s arrival in the USA towards the end of 1940 was full of promise, but that health and financial difficulties soon began to take their toll. The music he produced in his American years is characteristic for its mellowness and accessibility, whilst clearly retaining the influence of his native traditional music. The Piano Concerto No. 3 is a good example of this. It was composed for his wife, Ditta, to perform, with some allowances made to accommodate her smaller hands, as well as toning down the virtuosity required to play it. There is a significant difference, then, between this concerto and its immediate predecessor, and even more so with the uncompromising first concerto. Comments by Tzimon Barto quoted in the booklet demonstrate that he is at pains to tease out what lyricism is present in the earlier works, and that tendency is even more marked in his performance of No. 3 where, one would think, no such help is required. The opening theme, for instance, with the pianist’s hands two octaves apart, is given an almost romantic treatment, slow, smooth and expressive to the point of ironing out the tautness of rhythm we are used to from other performances. This is sustained throughout the movement, where the tempo is very relaxed indeed: at 9½ minutes, Barto takes a full two minutes more than any rival, including Martha Argerich with Dutoit (1997, EMI/Warner). If one can accept this quite different view of the music Barto’s magnetic playing may well convince the listener. Less likely, I fear, the Adagio religioso slow movement, where he adds a whopping three minutes to the time needed by Argerich, and nearly four to Jandó! The score specifies a speed of 69 beats to the minute, but in certain passages, usually where Barto is playing unaccompanied, the music moves forward at less than 40, a real test of the listener’s patience. The finale is given a more orthodox reading where the spectacular playing provokes an enthusiastic reception from the audience in this live recording.

Tzimon Barto’s readings of the first two concertos are refreshing and satisfying, without necessarily effacing memories of other performances. The third concerto is another matter. Some will find it idiosyncratic, perhaps even bland. The orchestral playing in all three works is predictably fine, and always at one with the soloist’s conception. Christoph Eschenbach is, of course, a pianist, and I wonder how he felt about his soloist’s tempi in the third concerto. The discrepancy between solo and orchestral passages in the slow movement lead me to suspect that he was not in full agreement. The recordings, in two different venues, are very fine, with a near-ideal balance between soloist and orchestra. If the strings seem rather recessed this rather suits the way the music is written.

Anyone wanting all three concertos will find Géza Anda a satisfying companion. Jenő Jandó is also very fine, though a little less vivid. Both these issues fit the three concertos on to a single disc, as do numerous more recent – and enticing – performances.

William Hedley

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.