Déjà Review: this review was first published in November 2003 and the recording is still available.

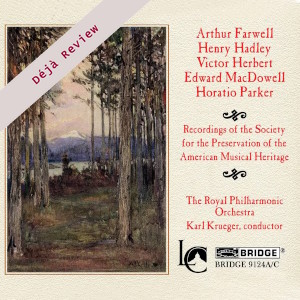

Recordings of the Society for the Preservation of the American Musical Heritage

Royal Philharmonic Orchestra/Karl Krueger

rec. 1960s, ADD

Bridge 9124A/C [3 CDs: 198]

This is the third volume in Bridge’s restoration of Karl Krueger’s SPAMH recordings. The Society’s Herculean efforts resulted in the recording of much totally neglected American orchestral music from the nineteenth century (and earlier). In addition to recording substantial orchestral scores by Louis Coerne (Excalibur), Bristow and John Knowles Paine there was room for chamber music by John Antes, choral works by Billings and traditional singing from the Appalachias. By the time the Society had finished they had produced over one hundred LPs. These were distributed on a library basis rather than being commercial issues. When the SPAMH LPs were disgorged onto the market this came about when the Society was on its last legs and was offering to give their remaining stock of LPs away free.

My introduction to its existence was a substantial two part article on the SPAMH series. This was by the great Richard D.C. Noble and it appeared in the UK in late 1970s issues of Cis Amaral’s ‘Records and Recordings’ magazine – a home of literate and inspirationally knowledgeable writing about classical music. I made contact with Richard and he was kind enough during the early 1980s to make a series of cassettes from these so that I could hear the music.

Krueger was born in Atchison, Kansas in 1894. He studied in Vienna with Robert Fuchs (whose works are being recorded complete by Thorofon) and Franz Schalk. After a spell as assistant conductor of the Vienna Staatsoper he held various music director positions: Seattle (1925-32); Kansas City (1933-43) and Detroit (1943-49). He founded the Society for the Promotion of the American Musical Heritage in 1958.

The Macdowell First Suite (like the Second) was premiered in Boston conducted by Emil Pauer. It starts with an uncharacteristically dramatic In a Haunted Forest. There is a touch of Tchaikovsky’s Hamlet here. The other movements are ebullient (Chabrier), cheeky (Dukas) and poetic (Grieg and the cooler Tchaikovsky) in the way of light music but by no means demonstrating the bleached charm of his piano miniatures. Krueger and the RPO give what is the best performance I have ever heard of the piece. It is full of vigorous restlessness, sparkle and poetry.

They are scarcely less triumphant in the much more famous Second Suite The Indian. Like the First Suite this is in five titled movements. Once again the territory is Lisztian; indeed the Legend first movement reminds me of moments from Liszt’s Faust Symphony and there are echoes of Sibelius’s Kullervo and First Symphony. While there are some flavours of native Indian music they are by no means prominent. The auburn-toned balm of the Love-Song second movement is very effective. Macdowell cannot muster real threat. In the In War-Time movement the music is instead jauntily cheerful rather than grippingly threatening with similarities to the Abruzzi dances in Berlioz’s Harold in Italy. The Dirge is a fresh piece of affecting writing rather like the Love-Song. It has something of the best of Grieg about it – dark and reflective. The finale Village Festival. If you rate Glazunov’s orchestral suites or perhaps those of Ludolf Nielsen (Dacapo) then this is cut from similar cloth. This recording easily outstrips the competition (Hanson on Mercury and Landau on Vox).

Horatio Parker, the teacher of Sessions, Porter and Moore is best known for his oratorio Hora Novissima (it even achieved a Three Choirs performance) and his opera Mona premiered at the Met in 1912. Vathek was inspired by the gothic fantasy novella of the same name by William Beckford (1759-1844). Vathek is the name of a Caliph whose incredible wealth enabled him to indulge every sensuous instinct. He enters into a compact with Eblis (the Devil figure) for forbidden knowledge but Eblis betrays and abandons him to writhe in eternal agony in the Palace of Subterranean Fire. The reference points here are Tchaikovsky’s Francesca da Rimini, Elgar’s Second Symphony, Franck’s Psyché and the early Miaskovsky symphonies (1-4). The piece ends in golden harmonic light as indeed does the Herbert poem that follows it.

The Hero and Leander symphonic poem is not the only concert-piece by Herbert in the catalogue. Marco Polo issued a disc that included his Auditorium Festival March, Irish Rhapsody and Columbus Suite with the Slovak Radio Symphony Orchestra and Keith Brion (8.225109). Hero and Leander is a full-on symphonic poem – a substantial piece running to almost half an hour.

The legend of Hero and Leander has Hero as a prophetess of Aphrodite living in a tower overlooking the Bosphorus. Leander, her lover, swims the straits each night until drowned in a storm. Hero in despair jumps to her death and Poseidon restores the lovers to life as a pair of birds. The Love-Scene second episode has some eldritch writing reminiscent of the macabre writing in The Nutcracker. This is a gorgeous tone poem in the tradition of Holbrooke (Ulalume, Queen Mab and The Raven) and Bantock (Witch of Atlas and Dante and Beatrice) without quite the exalted exotic flair of a Griffes or a Parker.

Arthur Farwell‘s suite of music for the Oriental-themed play by Lord Dunsany is as richly imagined and expressed as Griffes’ Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan. Bracket the style of this piece somewhere between the exotic works of Adolphe Biarent (Contes d’Orient on Cyprès), Mily Balakirev (Tamara) and Rimsky-Korsakov (Antar). The remorseless bluntly ungainly thuds gaining in volume and range as the finale The Stone Gods Return progresses. This suite follows a savage and exotic tale with beggars outside the city of Kongros impersonating the city’s stone gods and enjoying a brief heighday of sensual indulgence before the real gods return Golem-like and avenge the impiety by turning the beggar impostors to stone. The people take the petrification of the beggars as verification of the pretenders’ status as Gods.

Henry Hadley who conducted the New York premiere of The Gods of the Mountains in 1931 was born in Massachusetts and studied in Vienna. He was the conductor of the Seattle, San Francisco and New York orchestras. He was a determined champion of American music who included American music in every programme. He was an early supporter of music radio broadcasts giving many studio concerts during the early days of radio. He wrote four symphonies of which the Second is The Four Seasons (starting with Winter). This is, in layout and achievement, similar to the Raff, Huber and Rubinstein symphonies. The idiom which never lacks distinction veers from Tchaikovsky (suites and ballets) to Grieg (Gynt and the Symphonic Dances) to Smetana (Ma Vlast) to Glazunov (The Seasons), discursive and illustrative rather than epic or tragic. As if to confirm this the work ends with a modest gesture from the violins. I detected a little more wear on the original tapes for this symphony than on the other items in this munificent set.

Hadley’s Salome was inspired by seeing Oscar Wilde’s play. The plotline is related to episodes in the story rather like the annotated tone poem scores of Joseph Holbrooke. The use of the orchestra is sophisticated with exotic sinuous flavouring from the woodwind. Parts of it link with the contemporaneous Sibelius tone poem Pohjola’s Daughter and with Liszt’s Faust Symphony. The by turns rapturous, restive and troubled late-romanticism of this score has about it less of Strauss and more of what we now recognise as Bantock and Holbrooke. If some of the tracks have something of the music (e.g. tr.9) for a dumbshow/mime about them, the Dance of the Seven Veils and the Death of Salome have weight and emotional impact.

The very extensive English only notes are by Malcolm Macdonald and they provide us with extensive background – a veritable encyclopaedic entry for each piece. I lament only the absence of a detailed account of the history of the SPAMH project. There is a fascinating story to be told, I am sure.

The playing of the RPO is superlative and the close-up rugged analogue sound does gripping justice to everyone’s commitment. Listen to the dazzling pizzicato at the start of the last movement of MacDowell’s second suite.

Rob Barnett

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Contents

Edward Macdowell (1860-1908)

Suite No. 1 in D minor Op. 42 (1891)

Suite No. 2 Indian Op. 48 (1892)

Horatio Parker (1863-1919)

Vathek – symphonic poem (1903)

Victor Herbert (1859-1924)

Hero and Leander – symphonic poem Op. 33 (1900)

Arthur Farwell (1877-1952)

The Gods of the Mountains – suite Op. 52 (1916)

Henry Hadley (1871-1939)

Symphony No. 2 in F minor Op. 30 (1901)

Salome – symphonic poem (1905-6)