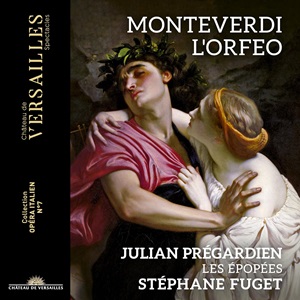

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

L’Orfeo – Favola in musica

Opera in a Prologue and Five Acts. Libretto by Alessandro Striggio (1607)

Cast listed after review

Les Épopées/Stéphane Fuget (harpsichord, organ, direction)

rec. 2022-23, Château de Versailles, France

Booklet with notes, texts and translations in Italian, French, English and German.

Château de Versailles Spectacles CVS103 [2 CDs: 117]

In 1607, Claudio Monteverdi premiered his L’Orfeo at the court theatre of the Duke of Gonzaga in Mantua. The year 1600 had first seen this type of creation: Jacopo Peri’s L’Euridice was a staged presentation of myth believed to resurrect the manner of classical Greek tragedy in performance, with instrumental music and singing throughout. The singing style, the more melodic seconda pratica, deployed the flexible recitar cantando developed in Florence, a monodic style to succeed the older established polyphonic style of Renaissance madrigals. One hears this type of poetic alliance of text and notes everywhere in L’Orfeo, with the shared pathos and eloquence between recitative and aria, where the text becomes strophic. That would become much more ossified in the 18th century, with its regular alternations of secco [dry] recitative and full aria. Here was a new work in a new style and opera’s first masterpiece, in some ways hardly surpassed since.

In this new recording, the founder and musical director of Les Épopées, Stéphane Fuget, had choices to consider, as he explained in an interview with Robert Hugill. Any group of performers needs to make decisions, even given the quite full surviving printed material. The score lists the instruments, but the music is not fully written out; there are gaps, which requires performers to be creative. Three trumpets are listed but appear only in the opening toccata: the sound seems to launch the 17th century in music. Here they also repeat in a near/far echo, to a fine effect, of the violin phrases that accompany Orfeo’s appeal to visit the underworld. Several such choices of instrumental colour and vocal decoration will delight the ear, even (perhaps especially) if you know the work well in a recording which takes different musical options. Fuget also notes that the instrumental writing is usually in five parts, and that allows a type of broken consort with different combinations at different points.

For Orpheus, Fuget sought a singer whose style of delivery ranged from fragility to pain and rage. It seems he knew well Julian Prégardien, a singer who would be willing to try new ways. Prégardien delivers a remarkable account of this demanding title role. It is generally very well sung but at times projects the drama even at the expense of vocal propriety. Thus Rosa del ciel, his delayed entry in Act 1 (CD1, track 8), is a poised expression of sublime happiness on the day of his wedding to his beloved Euridice. His voice also manages to convey something of the stress of such strong emotion, almost as if he is even now conscious of what the loss of Euridice would mean.

Orfeo opens Act 2 with a lively address to the hills and woods, which Prégardien sings with rhythmic liveliness. He then hears of his disastrous loss, when his distress registers at the lines “You are gone from me, never to return, and I remain? No!” That “No” is not sung but shouted, almost barked, vocal decorum abandoned for dramatic realism. For, Orfeo has made a plan to visit the underworld and bring Euridice back. But to get there, he needs a lift from the ferryman Charon (Caronte) across the River Styx to Hades. In a long scene, he seeks to persuade Caronte. Possente spirto [powerful spirit] is the centrepiece of the drama. When the ferryman refuses Orfeo’s beautifully sung plea for passage, the dramatic manner again brushes aside vocal propriety (CD2, track 8). Caronte is reluctant to help but falls asleep at such fine singing, as well he might.

The other singers are on a par with Prégardien in favouring a theatrical manner at times. The spectacle was recorded live over several Versailles performances, to judge from the dates widespread for a work playing for 110 minutes. Doubtless the presence of an audience, and the views of director Fuget himself, ensured vocal and theatrical uniformity. The main female role is not Euridice, although Juliette Mey, who also sings La Musica, is excellent as both. Rather, it is Isabelle Druet as the Messagiera, who reports Euridice’s passing most poignantly, and sings Speranza [hope] with grace and authority. The casting is very even, with no weak link.

The diction is clear, too, as it must be, given that Striggio’s text is as important to the work’s conception as the music – perhaps more so, for it was reproduced in booklets handed out to the first audiences. The choral sound is also large and dramatic for just 17 singers, all listed in the booklet. The instrumental music is a delight throughout. This is Stéphane Fuget’s area of expertise, after all, and Les Épopées sound very expert indeed. The sound of their authentic instruments might take you right back to Mantua in 1607. There is a valuable booklet with notes on the background to the work’s origins and conception. The sound, immediate yet atmospheric, captures the tang of those early instruments.

Those who want a more purist vocal approach may consider La Venexiana’s recording (review), but this account should certainly be heard if one wishes for a second version, likely quite different from their current favourite.

Roy Westbrook

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Cast

Julian Prégardien: Orfeo

Juliette Mey: Euridice, Musica

Claire Lefilliâtre: Proserpina, Ninfa

Isabelle Druet: Messagiera, Speranza

Luigi De Donato: Plutone Caronte, Pastore, Spirito

Cyril Auvity: Apollo, Pastor, Spirito

Paul Figuier: Pastor

Vlad Crosman: Pastor, Spirito, Eco

Samuel Guibal: Spirito