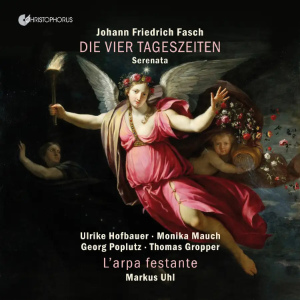

Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688-1758)

Die Vier Tageszeiten

Ulrike Hofbauer (soprano); Monika Mauch (contralto); Georg Poplutz (tenor); Thomas Gropper (bass)

L’arpa festante/Markus Uhl

rec. 2023, Martinskirche, Müllheim, Germany

Texts included; no translations

Reviewed as a 24/96 download

Christophorus CHR77480 [65]

For a long time Johann Sebastian Bach was the dominant German composer from the first half of the 18th century, as far as performance practice is concerned. It is only since the end of the last century that Telemann’s oeuvre has been given serious attention. Today Christoph Graupner makes the headlines; in recent years, quite a number of discs with his cantatas have been released. In comparison, their contemporary Johann Friedrich Fasch still awaits rediscovery.

In his own time, Fasch was a man of fame, whose works were known far beyond the regions where he worked. One of the most important of these was Leipzig, where he became a member of the Thomasschule at the age of thirteen. He came under the influence of Georg Philipp Telemann, who arrived in Leipzig at the same time. Fasch, who had taught himself to play the keyboard and the violin, started to compose like Telemann, which he did with so much success that some of his works were performed by the Collegium Musicum. In Leipzig he also got to know music from elsewhere in Europe – in particular, the concertos of Vivaldi.

In 1708, he started studying law at Leipzig University, and founded a second Collegium Musicum, in which musicians took part who later ranked among the most famous in Germany. These included Pisendel, Heinichen and Stölzel. From 1712 onwards, he travelled through Germany and worked in Gera, Greiz and Prague respectively, until he became Kapellmeister at the court of Anhalt-Zerbst in 1722. He refused the invitation to become Thomaskantor in Leipzig as successor to Johann Kuhnau. He stayed in Zerbst until his death in 1758.

As Kapellmeister he composed a large number of sacred works, among them nine cantata cycles, all of which have been lost. According to the work-list in New Grove, only 66 individual cantatas have survived, as well as some masses and mass movements. There is also a Passion on the well-known text by Brockes. The main part of his oeuvre which has come down to us consists of concertos (64) and overtures (87). Although a player of the keyboard and the violin by profession, one of the features of his orchestral music is the prominence of wind instruments, in particular the oboe and the bassoon.

The disc under review is devoted to a serenata, a popular genre in the 18th century. Serenatas were written to pay homage to a particular person, often a royal or aristocratic ruler, at a special occasion, such as the birth of a heir, a wedding or a birthday. The latter is the case with the serenata Freudenbezeugung der Vier Tageszeiten – The Joyful Testimony of the Four Times of Day. It dates from 1723 and was performed on 9 August, the birthday of Prince Johann August (1677-1742) of Anhalt-Zerbst.

Serenatas can be different in complexion: they were usually performed in a concertante form, but could be staged. Whether that was the case with this particular serenata is not known. The libretto was written by Fasch himself. The scoring is for four voices (soli and tutti) and an orchestra of three trumpets, timpani, two recorders, two oboes, strings and basso continuo. The four solo voices are connected to allegorical figures. Cynthia (soprano) represents the night, Aurora (alto) the morning, Phoebus (tenor) the noon and Hesperus (bass) the night. They sing the praises of the ruler from different perspectives.

In the Prologue, Phoebus sets the tone: “The smoke from your sacrificial embers has even exceeded the stars. Then comes the requested good for Anhalt’s state and princely guard in the form of blessings, well-being and pleasure.” The smoke is graphically depicted in the string parts, and in the ascending figures in the vocal part. The ensuing recitative attests to the fact that at the time there was no watershed between the sacred and the secular. “That people on earth become great and powerful above others does not happen by chance, not through themselves, no, it comes from heaven, which allows people to move when they bow down before it and lie down humbly.” Next is a chorus, which is in fact an aria à 4, as the four voices mainly sing their own text, first individually and then together. Like all arias, the chorus is written in da capo form.

The four characters then present themselves, in the order of noon, evening, night and morning. Next, each of them has a recitative and an aria of his own. In three of the arias wind instruments have obbligato parts: Aurora has two oboes, Phoebus a trumpet, and Cynthia two recorders. The most spectacular aria is that of Phoebus, who gets involved in virtuosic coloratura with the trumpet. Notable in the aria of Hesperus are bars in which the strings play pizzicato, depicting the text: “Strike you, hours, and divide the times, but also give glory and thanks.” It is not surprising that two soft recorders participate in Cynthia’s aria: “Sleep, ruler of this land, for heaven watches over you.”

In the last recitative Phoebus asks the ruler: “Then direct a glance of grace from your throne down upon our weakness”, and to remember that the citizens wish him well with the words of the closing chorus: “Long live Prince Johann August, let everything that separates him from his well-being flee.”

Several composers have written music about the times of the day. The best-known of them is Haydn, who composed three symphonies in the early 1760s. Not long before, in 1759, Telemann composed a cantata with the title Die Tageszeiten. That is an entirely different work, which is divided into four sections, each performed by a singer representing one of the stages of the day. The text is mainly about nature, and that puts it in the same category as the German arias on texts by Brockes, which were set by Handel. In Fasch’s work the sections of the day are represented by allegorical figures whose main aim is to praise the ruler. In character, serenatas were often quite similar to operas, for instance in the way the arias are written. That is also the case here. The arias in Fasch’s serenata would not be out of place in an opera by Telemann, for instance. Fasch was clearly a master in writing for the voice; one has to regret that his four operas have all been lost. At the same time, one can admire here his writing for instruments; the brilliant trumpet part mentioned above is just one example. He effectively uses orchestral colours to depict an aria’s content.

This serenata has been performed in the past, but this is the first commercial recording. It could not have received a better performance that it gets here. The four soloists do a great job: the singing is excellent, technically and stylistically. They do just everything right. The playing of the orchestra is energetic and colourful, but also – when needed – very subtle and full of expression.

This is a disc to treasure, and a worthy monument for a composer who still does not receive the attention he deserves. This recording should help to set things right.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free