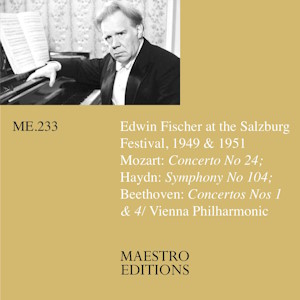

Edwin Fischer (piano)

The 1949 and 1951 Salzburg Concerts

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791)

Piano Concerto No. 24 in C minor, K491 (1786)

Joseph Haydn (1732-1809)

Symphony No. 104 in D major ‘London’, Hob.I:104 (1795)

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 (1795-1800)

Piano Concerto No. 4 in G major Op.58 (1806)

Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra/Edwin Fischer (piano)

rec. 30 July 1951 & 1 August 1949 (Beethoven Concerto 4), Mozarteum, Salzburg

Maestro Editions ME233 [2 CDs: 123]

These performances, given by Edwin Fischer and the Vienna Philharmonic at the Salzburg Festivals of 1949 and 1951, are making their first appearances in this twofer release. The tapes were in the possession of Paul Badura-Skoda and were lent to Roger Smithson for digitisation and restoration. They offer some real aural challenges but expert remastering has mitigated many of those obstacles and allow one to listen to them in relative ease. There are three concertos and one symphony and Fischer directs from the keyboard and in the Haydn Symphony, from the rostrum.

The performance on 30 July 1951 at the Mozarteum, Salzburg, contained Mozart’s Concerto No.24, Beethoven’s Concerto No.1 and Haydn’s Symphony 104. Fischer had recorded the Mozart pre-war in London with Lawrence Collingwood conducting Beecham’s LPO but there is also a surviving example live, post-war in 1954 with the Royal Danish, where Fischer also directs. This Salzburg performance finds Fischer on leonine form generating a real sense of electricity at the keyboard, not least in his sculpting of the bass. He’s not finger perfect and misses a few notes in his own cadenza and the first clarinet, as the notes relate, misses an entry and Fischer, with lightning reflexes, fills in for him. The winds are characterful in the central movement and Fischer phrases with his characteristic beauty, although here, and in the finale, he continues to split and drop the occasional note. It’s in the finale that his animated vigour and gruff vitality pay the richest dividends, and it’s a more visceral, vital Fischer than the one found in the studio in 1937, even though his cadenza is decidedly jocular. Fischer’s cadenzas were very much a matter of taste.

Fischer recorded the Haydn Symphony with his own Chamber Orchestra on 78s and greater mobility and lighter orchestral mass are certainly a real point of departure from this Vienna Philharmonic performance – as well as the fact that this is a live performance, of course. In terms of timings, however, there’s surprisingly little in it. In Berlin in 1938 Fischer took just over 23 minutes and in Salzburg in 1951 he takes merely nearly 90 seconds longer. The scale of the basses and the very audible percussion – which can boom in the acoustic – are the major differences.

Beethoven’s First Concerto is a lacuna in Fischer’s commercial discography, though there are other live survivors. There is some noise on the tape but it sounds better than expected in this restoration. Fischer brings real communicative élan to it and he makes it sound like the big work it is. There’s nothing small-scaled about his playing, nor the orchestra’s, and his cadenza is witty and alive. The final work is the Fourth Concerto from the 1949 festival, which was recorded on 12” transcription discs, one or two sides of which, it’s reported in the notes, remain noisy. What we hear is a tape copy of those discs and this is the only known survivor of Fischer’s appearances at the festival that year. Certainly, the sound is rough in comparison with Fischer’s 1954 studio recording with the Philharmonia but once more there are compensations in the intensity of a live recording, however imperfect. Fischer uses his own cadenza in the opening movement. Unfortunately, the transcription disc containing the opening of the slow movement is one of the noisiest and the chuffing is distracting, at least until 3:18 where things improve somewhat. The orchestra sounds muffled and dull, especially in the finale, where the pianist uses Eugen d’Albert’s cadenza. It’s not always an easy listen but it’s by no means impossible.

Of course, listening to these two discs one doesn’t have the opportunity for a before-and-after comparison so one won’t be able to appreciate the hard work done in restoration that allows these live performances to be heard at all. Andrew Hallifax’s transfers have clearly extracted the best possible sound from the tapes and have mitigated the many problems associated with the originals. His one-page restorer’s note is in the booklet as is Roger Smithson’s note about the origins and provenance of the surviving tapes. There’s a fine but unsigned five-page note on Fischer and his performances (is it by Smithson?) and the relevant programme from the 1951 festival is reprinted.

You can never have too many restorations of Edwin Fischer’s humane art on disc and this undertaking, itself touched with a degree of heroism, provides a real insight, however occasionally fragile, into his great musicianship.

Jonathan Woolf

Availability: Maestro Editions