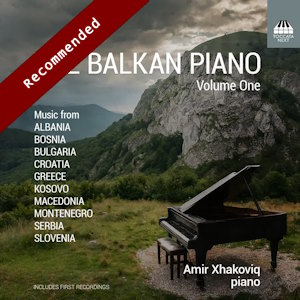

The Balkan Piano Volume One

Amir Xhakoviq (piano)

rec. 2024, Concert Hall, Svetosavski Dom, Niš, Serbia

Toccata Next TOCN0034 [59]

Toccata Classics does it again. The composers here, with ties to ten Balkan countries, are mostly unknown in the West. For many years, we have ignored the region. There was little interest in exploring music from behind the iron curtain. The narrative, if any, usually was that the music from those countries was almost impossible to obtain in manuscript form or on disc. (I had no difficulty buying discs from various of them.) Another reason was presumably that the state discriminated against the composers who struggled to get their work heard even at home; in some cases, that was regrettably true. It is wonderful to hear such music now, and what is on this disc is much more than purely interesting.

Pianist Amir Xhakoviq designed the programme, and penned the most informative booklet notes, acknowledge here with thanks.

To launch it, there is a firecracker of a piece, a real adrenalin rush. Croatian Sanja Drakuli’s Drive fairly leaps out of the speakers. It grabs you by the ears and speeds along in an exciting version of John Adams’s Short ride in a fast machine. Calm is restored momentarily before we are rushed off again, negotiating more musical hairpin bends to delight the senses, and then we arrive to an abrupt stop and can catch our breath.

Switzerland-born Bulgarian Pancho Vladigerov may be the composer here of whom some people are already aware of. He wrote the marvellously rhapsodic Improvisation, the fourth of his Épisodes, during the second World War, but the atmosphere has no hints of war. The short work weaves traditional Bulgarian rhythmic modes and styles in a gently expressed oasis of calm amidst the turmoil.

Moving south-west to Macedonia, we meet Tomislav Zografski and his Suite for Piano, a homage to the Baroque and Classical periods, encapsulated in five movements and five minutes. It sets off with an impressive echo of Scarlatti’s time but soon bridges the gap to modern times. The idea is to look back from now to the past and back to the present. An improvisatory section incorporates the past through a 20th-century prism before reverting to the gentle interlude. The opening style concludes the suite. On to Kosovo. Rafet Rudi’s atmospheric Këmbanator arbëreshe [arbëreshe bells] is the opening part of Arbëresh Fresco that describes the tradition of church singing developed in the 400 years of Ottoman occupation. These traditions emerged among the Albanian communities that fled to Southern Italy and Sicily, and survive until today. They are known as the Arbëreshë, the speakers of Arbërisht, an ancient variant of Albanian. Rafet Rudi accomplishes the bell-like sound, persuasive and effective. The notes say that the next stop in this Balkan musical tour is Croatia / Serbia / Bosnia and Hercergovina / Montenegro. Vojin Komadina obviously draws his roots from all those places. Two Minuets, a delightful reworking of old French dances, come from a collection entitled To Youth. These short pieces are indeed full of youthful vigour. Slovenian composer Dušan Bavdek’s work Awakening also finds its inspiration in youth. It is inspired by the poem of the same name by modernist Slovenian poet Oton Župančič from his book Young Paths. We arrive in Albania, the birthplace of pianist Amir Xhakoviq and composer Aleksandër Peçi. Barokjare draws inspiration from the improvised singing, jare, which originates in the area of Albania’s fifth largest city Skodër. Peçi has successfully fused the jare style with Baroque influence in a very original melding of these very distinct styles into a innovative whole. It is not far from Albania to Montenegro, where composer Aleksandar Perunović was born. Musically the journey is much longer. Metaglasswork, a commission by French pianist Nicolas Horvath, was to use it as part of the vast project in which he played the complete piano music of Philip Glass and almost a hundred commissions from the world over. In this piece, the composer takes Glass’s Music Box from the movie Candyman. As if it were a piece of real glass, he smashes it into fragments and then reconstructs it. In the process, he uses dissonance and occasionally quite threatening sounds to create a mosaic that makes more sense with each repeated hearing. It brought to my mind what Vaughan Williams said of his 4th symphony: “I can’t say that I like it, but it’s what I meant”. There is clearly no reason to suspect that Perunović feels the same.

Scriabin’s influences pervade Serbian composer Milan Mihajlović’s Three Preludes. They quickly achieved huge success, and were performed right across Europe and as far afield as Mexico. They became a mandatory composition for participants at the International Music Youth Competition. All three create an almost otherworldly atmosphere that certainly chimes with Scriabin’s musical vision. The second prelude uses the tetrachord which “helped pave the way for twentieth century atonality”, according to the booklet notes. It made me intent on revisiting Scriabin’s work to find those influences.

The last piece in this conspectus of Balkan piano music lands us in Greece with Jettatura, a piece by New Zealander John Psathas, the son of Greek immigrants. Incidents that happened to him on almost every visit to Greece, none of them pleasant, were the influence behind this piece. The events made people say that he was affected by the evil eye, especially following a particularly nasty incident that affected his wife and son. That led his sister to consult the local expert on such matters and, following a consultation by phone, it was concluded that poor Psathas was well and truly bewitched.

In Italian, “jettatura” means a curse of the evil eye. There is a talisman in Greece that wards off such evil, a glass blue eye. The piece, Psathas says, “is my talisman, my good eye”. This fascinating work compels repeated listenings with a fragile beauty of cascading notes like a tumbling waterfall. I fervently hope that it works for this brilliantly innovative composer.

I am in awe of the wealth of talent on display in the programme, and the variety that emerges from this fascinating area of Europe that experienced devastating trauma in the last 25 years. If music can prove a salve and a unifying force, and I absolutely believe it can, then this demonstration of collective talent should help put aside the awful events that consumed so many parts of the Balkan peninsula. This disc is Volume One. I literally cannot wait to be introduced to more compositional talent from this region.

These fabulous works have a champion eminently worthy of presenting them in their best possible light. The Albanian pianist Amir Xhakoviq is a truly prodigious talent, and for several pieces on the disc nothing less would have done.

Steve Arloff

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Sanja Drakulić (b.1963) Croatia Drive

Pancho Vladigerov (1899-1978) Bulgaria Épisodes, Op.36, No.4 Improvisation* (1941)

Tomislav Zografski (1934-2000) Macedonia Suite for Piano in A major, Op.27* (1960)

Rafet Rudi (b.1949) Kosovo Preludium – Les cloches Arbëresh (1993)

Vojin Komadina (1933-1997) Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia and Hercegovina, Montenegro Two Minuets (1985)

Dušan Bavdek (b.1971) Slovenia Awakening (2010)

Aleksandër Peçi (b.1951) Albania Barokjare (2013)

Aleksandar Perunović (b.1978) Montenegro Metaglasswork (2014)

Milan Mihajlović (b.1945) Serbia Three Preludes* (1986-1989)

John Psathas (b.1966) Greece, New Zealand Jettatura* (1999)

Except *, these are first recordings.