Charles Ives (1874-1954)

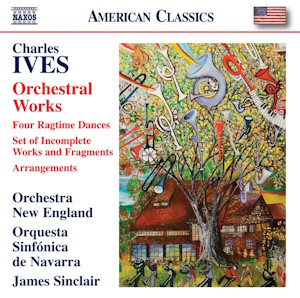

Orchestral Works

Orchestra New England, Orquesta Sinfónica de Navarra/James Sinclair

rec. 2023/24, Auditorio Barañáin, Pamplona, Navarra, Spain; Colony Hall, Choate Rosemary Hall, Wallingford, USA

Reviewed as a 24/88 download

Naxos 8.559954 [76]

Taking a quotation from the Charles Ives Society website, “the paradox of Ives’s music, echoes his paradoxical personality. He could be realistic, comic, transcendent, simple, complex, American, and European, all at the same time. If some of his music seems crowded nearly to bursting, it is a vibrant and entirely realistic portrayal of his conception of life, his sense of democracy in action, and of his own all-embracing consciousness. As Ives once said, “Music is life.” Listening to this excellent CD, that description seems to fit perfectly.

Part of the Naxos series of the complete orchestral works of Charles Ives, this album collects the miscellanea of his numerous shorter pieces. Ives was a master of miniatures, marches, short sets, experiments and many songs some merely a minute-and-a-half in duration. The music presented here is a blend of remarkable variety. We can hear ragtime pieces, several engaging dreamy tunes, other experimental ones, a startling original chromatic piece, marches, atonal fugues, arrangements of classical repertoire, plus a set of incomplete works and fragments stitched together. Underpinning them all is a liberal use of well-known American tunes. The CD demonstrates the significant skill Ives had as a composer

Charles Ives embraced ragtime even before it became a craze in the late 1890s. Ragtime is, of course, short for ragged time; where the instruments are not necessarily playing the same time signature. At the turn of the century he produced about a dozen rag sketches. By 1902 and 1904 he pared these down to a favourite few. While the ragtime idiom was frowned upon by Ives’ peers as the stuff of a red-light district, his Four Ragtime Dances are each based on three hymn tunes: in the main sections of each i.e. The “Verse”, Bringing in the Sheaves and O Happy Day; in the closing section i.e. The “Refrain”, I Hear Thy Welcome Voice. O Happy Day is probably best known with its decidedly non-religious lyrics. The sacred and profane joys become one.

Rag No.1 involves a piano melody interspersed with louder brass and percussion, in a stop/start tune – strings are used in the refrain to calm it all down. Rag No. 2 follows a similar pattern but perhaps is not as frantic as the first; there is a lovely melody in the refrain. No. 3 includes a bell and again there is a play-off between piano and the louder, bolder instruments until the closing refrain. At the close of rag No. 4 one hears the piling up of two dominant chords (E and F) followed by a cadence in B flat. The piano drops in a delayed A chord which then disappears into the sustaining B flat chord in the strings.

The Fugue in Four Keys on The Shining Shore is an example of the kind of experimentation that annoyed Ives’s music professor at Yale in the late 1890s. His teacher was Horatio Parker, a German-trained American who was distant, demanding, and conservative. Nevertheless Ives’s Fugue in Four Keys creates a rather beautiful harmonic haze for his setting of the hymn tune The Shining Shore including a bit of the Azmon hymn tune as well. The result is wistful, nostalgic piece featuring a repeated brass refrain which works well.

Ives created several versions of the music in the short piece the Pond. The version on this CD uses flute, flugelhorn, harps, piano, and strings. It has a lovely dreamy feeling and is over far too soon. Ives later reduced this music for the song Remembrance as a memorial for the 1894 loss of his father, George Edward Ives. Shortly after he began at Yale University, came the greatest blow of Charles Ives’s life: his father died suddenly of a stroke. George was most instrumental in developing Charles’ love and bent for music. He never came to terms with it; he spoke of his father often until to the end of his life, and seemed to feel that he was writing George Ives’ music. Despite lingering depression over his loss, Ives had a spectacularly successful career at Yale in every way but academically. His average in musical courses was a respectable B, in everything else D+. He spent his four years enjoying himself in various clubs, playing intramural sports, frequenting vaudeville theatres and sitting in for the pianists, playing ragtime and his own pieces at parties, as well as composing light pieces for band, glee clubs and church services, assigned works for his classes, and experiments.

The Rainbow comes in a number of colours (orchestrations, if you will). The version on the album uses flute, English horn, harp, organ, and strings. It’s a lovely gentle melody.

An Old Song Deranged is Ives’ lovely arrangement (with a self-mocking title) of his c. 1899–1901 song Songs my mother taught me which sets, in English translation, a poem by the Czech poet Adolf Heyduk “Songs my mother taught me in the days long vanished; / seldom from her eyelids were the teardrops banished. / Now I teach my children each melodious measure; / often tears are flowing from my memory’s treasure. / Songs my mother taught me in days long vanished; / seldom from her eyelids were the teardrops banished.”) The piano notes are reminiscent of tear drops falling, a beautiful piece very cleverly created.

Charles Ives was born in the small manufacturing town of Danbury, Connecticut, on October 20, 1874, two years before Brahms finished his First Symphony. During the Civil War his father George Ives had been the Union’s youngest bandmaster. When the war ended George had returned to Danbury to take up the unusual trade, in that business-oriented town, of musician. Ives may have composed a piece for the Danbury Fair in 1902 “for Tent Band … between Races … Labour Day 1902”. The manuscripts on which this Skit for Danbury Fair is based seem to date from around 1909. The music has a close relationship with Ragtime Dance No. 1 and No. 2. The ragtime influence can be heard right from the start of this lively piece.

The Gong on the Hook and Ladder or Firemen’s Parade Down Main Street was composed c. 1911 for a quintet of piano and strings (with optional fire bell). In 1934 Ives arranged it for small orchestra, apparently for grouping as a Set of Three Pieces along with Hallowe’en and The Pond. This grouping served as an entr’acte in a dance performance by Martha Graham and group that year. The piece is an experiment in the regularity of the ringing fire bell and the varying speed of the fire wagon, played by low strings, on the Main Street of Danbury, Connecticut; where the parade route went downhill, uphill, and down again. The winds and brass play in 7/8 above the basic fire bell duration and make references to three songs popular in Ives’ youth i.e. Few Days, Marching Through Georgia, and Oh, My Darling Clementine, often in canon, that is to say, one thing follows another as in a parade. It all rises to a climax, then briefly returns to the opening music. It feels to me that this “experiment” works rather well producing a charming, humorous piece.

Chromâtimelôdtune is a portmanteau of chromatic, time, melody, and tune with diacritics thrown in by Ives to mock European influences, it is one of Ives’ most startling creations. This is a chromatic piece based on an angular 12-tone melody and two 6-pitch sets of chordal constructs arpeggiated in the piano or stacked in the strings. At the same time it is witty and builds to a climax on a C major chord. The beat and underlying tune keeps the whole thing together.

The Tone Roads are experiments in atonal fuguing. Ives penned a memo: “Over the rough & Rocky roads our ole Forefathers strode on their way to the steepled Village Church or to the farmers Harvest Home Fair. So to the Town Meetings, where they got up and said whatever they thought regardless of consequences!”. The musical lines represent roads converging on Town Hall. As Ives wrote elsewhere: “If horses and wagons can go sometimes on different roads hill road, muddy road, rocky, straight, crooked, hilly hard road at the same time, and get to Main Street eventually – why can’t different instruments do different staffs?” The musical analogue to this latter thought is especially heard in Tone Roads No. 3. A putative Tone Roads No. 2 is now lost or was only projected. Both these pieces are well worth listening to and are another example of Ives’ inventiveness and skill as a composer.

Many of Ives’ enticing pieces are incomplete, and the fragments are suggestive of something larger to come. Kenneth Singleton and the conductor of the CD, James Sinclair gathered together their favourites and cobbled them into a single string called Set of Incomplete Works and Fragments. The assembled bits are, in order: March No. 4 in F and C (S. 32), Trio in C (S. 493), Clement is sick?!—no dinner (S. 497)*, Bi-tonal duet (S. 459)*, Polonaise (S. 78, here for two cornets), The baseball Take-Off No. 7: Mike Donlin−Johnny Evers (S. 47), March No. 3 in F and C [Part 1] (S. 30), Earth Sound (S. 601)*, Snow Drifts (S. 578)*, Mountain Calls (S. 631)*, In the Sweet Bye & Bye (S. 461)*, Sunrise over East Rock, My Bonnie Lies Over the Ocean (S. 447)*, The baseball Take-Off No. 8: Willy Keeler at Bat (S. 48), and March No. 3 in F and C [Part 2] (S. 30). *fragments orchestrated by James Sinclair. It’s a highly entertaining and enjoyable piece with several marches featured amongst many charming ditties and hints at familiar American tunes.

The CD features three wonderful marches. The two marches for theatre orchestra are based on popular tunes of the time: March No. 2 with the song Son of a Gambolier, and March No. 3 with My Old Kentucky Home. The third is March: The Circus Band, which picturesquely switches from a circus tent galop to a standard 6/8 street march; it exists only partially in a single surviving page of manuscript score. However, the resultant music on this CD certainly rivals a Sousa march of the same period.

While a student in Yale Professor Horatio Parker’s 1896–97 orchestration class, Ives produced at least a half-dozen arrangements of classical repertoire. They are effective and, at times, imaginative and creative. Only three of these are complete enough to perform today. The Schubert Impromptu in C minor required the restoration of mm. 175–198 of its 204 measures, due to missing score pages. Of note are Ives’ replacement in Schumann’s Valse of the accompaniment in mm. 9–24, in which he places a new running line in the violas and cellos. In Schubert’s Impromptu in C minor he adds motivic echoes in mm. 38–39 and replaces Schubert’s arpeggiated accompaniment in mm. 125–134 with an energetic running line which is reminiscent of Ives’s first variation in his organ work Variations on “America”.

I must offer my thanks to John Sinclair for the extensive notes in the CD booklet and the information belonging to the Charles Ives Society on their website. Both have been instrumental in enabling me to write this review.

My overall impression is that it’s a great CD really showcasing Ives’ grasp of traditional popular, and maybe not so popular, genres and his lifelong propensity for weaving familiar tunes into his work. This is a thoroughly enjoyable album.

Ken Talbot

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Charles Ives (1874 – 1954)

Four Ragtime Dances (1902–04, rev. 1916)

Fugue in Four Keys on “The Shining Shore” (c. 1903)

The Pond (c. 1906, rev. c. 1912–13)

The Rainbow (1914) (version 1)

An Old Song Deranged (c. 1903)

Skit for Danbury Fair(c. 1909) (incomplete)

The Gong on the Hook and Ladder or Firemen’s Parade on Main Street

(c. 1911) (version for ensemble 1934)

Chromâtimelôdtune (c. 1923)

Tone Roads No. 1(c. 1913–14)

Tone Roads No. 3 (c. 1911/1913–14)

Set of Incomplete Works and Fragments (sequenced and edited by Kenneth Singleton

and James Sinclair, 1974)

March No. 2, with “Son of a Gambolier” (c. 1892)

March No. 3, with “My Old Kentucky Home” (c. 1893)

March: The Circus Band (c. 1898–99/1932–33)

Franz Schubert (1797–1828)

Marche militaire in D major, Op. 51, D. 733, No. 1(1818) (arr. C. Ives, 1896–97)

Four Impromptus, Op. 90, D. 899 – No. 1 in C minor(1827) (arr. C. Ives)

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Carnaval, Op. 9 – No. 4. Valse noble (1834–35) (arr. C. Ives)