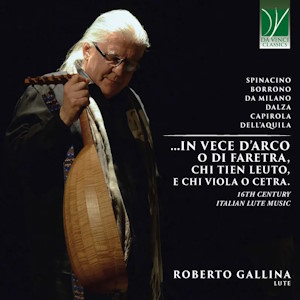

…In Vece D’Arco O Di Faretra, Chi Tien Leuto, E Chi Viola O Cetra

16th Century Italian Lute Music

Roberto Gallina (lute)

rec. 2020/23, Chiesa di San Domenico, Cagli, Italy

Reviewed as a 16/44 download

Da Vinci Classics C00894 [59]

For many centuries the lute was one of the most revered instruments. Its dominant position deteriorated during the 17th century, but even in the classical era some lutenists were highly regarded. In the Renaissance the lute was played everywhere. Royal and aristocratic courts could not do without one or several lutenists. They played music for lute solo, but also accompanied singers and instrumentalists. The present disc offers a survey of what was written in Italy in the first half of the 16th century.

Several genres are represented. Obviously, dances were an important part of the repertoire of lutenists. They constituted the more ‘popular’ part of the repertoire, probably with the exception of the pavana. Several composers ordered different dances to a kind of suites, such as Joan Ambrosio Dalza with a sequence of Pavana, saltarello and piva. The latter was one of the fastest dances at the time; it may originally have been a peasants’ dance.

Entirely different are the fantasias and ricercares. The former is the most free form of music and had its roots in the widespread practice of improvisation. Basically it has no fixed form and can give rein to the player’s imagination. It is in such pieces that a player could show what he was made of. The ricercare was mostly not fundamentally different from the fantasia. It is telling that in the work-list of one of the greatest lutenists of the time, Francesco da Milano, in New Grove, we read that he has left “91 ricercares or fantasias”. And in the track-list of the present disc we find a piece by Marco dell’Aquila, called Ricercar (Fantasia). Several pieces bear the title of La Spagna. This refers to a bassadanza tune, which has its origin in 15th century Italy. In later times it was often used as a cantus firmus, in particular in instrumental music.

Despite the fact that many pieces are of the same genre, they sound very different, which shows what a skilled composer can do with a particular form. All the composers represented in this recital were top of the bill in their time, but often we do know little about them. The most famous was the above-mentioned Francesco da Milano, who was nicknamed ‘the divine one’, and seemingly was able to spellbind his audience. Francesco Spinacino was another celebrity; he published two books of lute pieces which were the very first printed books dedicated to the lute. Dalza, already mentioned, focused on dances; whereas other lutenists often intabulated vocal works, he rather composed original pieces.

Dalza was from Milan, and so was Pietro Paolo Borrono. His oeuvre includes fantasias and dance suites; the programme offers one of the former genre and a pavane. Vincenzo Capirola was a nobleman from Brescia; he may have visited the court of Henry VIII in 1515. His works are collected in the so-called Capirola Lutebook; they vary from easy stuff to pieces that require an advanced technique. Very little is known about Marco dell’ (or dall’) Aquila; we don’t know where he was born or exactly when. His extant oeuvre is very small and includes fourteen fantasia-ricercares, two of which are included here.

Roberto Gallina has made a very personal choice from the large repertoire of Italian renaissance lute music. The recording took place at different times and with different technologies. This resulted in differences in sound. Those are clearly discernible, but it didn’t bother me. The recording is pretty direct, which gives the impression that one is just witnessing a player performing at his own pleasure. That is basically the case, as the first recording took place during the COVID pandemic. Gallina is a fine player, who shows his understanding of the repertoire in the differentiated way of playing. The dances are performed with rhythmic precision, and in the free pieces the improvisatory origins are kept alive.

This is a fine survey of Italian Renaissance lute music, which – especially because of the variety of genres – may also serve as a useful introduction to this important stage in music history.

Johan van Veen

www.musica-dei-donum.org

twitter.com/johanvanveen

Availability: Da Vinci Publishing

Contents

Francesco Spinacino (fl 1507)

Ricercare

Pietro Paolo Borrono (1490-1563)

Fantasia

Francesco da Milano (1497-1543)

Ricercar

La Terza

Joan Ambrosio Dalza (?-1508)

Pavana alla Venezia

Vincenzo Capirola (1473-?1548)

Ricercare X

Francesco da Milano

Fantasia

Vincenzo Capirola

La Spagna II

Francesco da Milano

Fantasia

Francesco Spinacino

Ricercare

Joan Ambrosio Dalza

Pavana, Saltarello e Piva alla Ferrarese

Francesco da Milano

Fantasia ‘La Compagna’

Ricercar

Vincenzo Capirola

Spagna I che mai impari

Francesco da Milano

Su Elizabeth Zacharie

Francesco Spinacino

Ricercare

Marco dell’Aquila (1480-1544)

Ricercar (Fantasia)

Francesco da Milano

Fantasia

Pietro Paolo Borrono

Pavana chiamata ‘La Milanesa’

Francesco da Milano

Fantasia

Marco dell’Aquila

Ricercare

Francesco da Milano

Fantasia VI