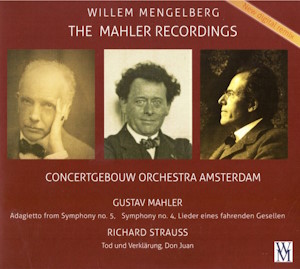

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

Symphony No. 5 in C sharp minor: Adagietto

Symphony No. 4 in G major

Lieder eines fahrended Gesellen

Richard Strauss (1864-1947)

Tod und Verklärung

Don Juan

Jo Vincent (soprano), Hermann Schey (baritone)

Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam/Willem Mengelberg

rec. live, 1926-42, Concertgebouw Amsterdam

The Willem Mengelberg Society WMS2020/21 [2 CDs: 122]

This is the second 2 CD set which has come my way from The Willem Mengelberg Society, The Netherlands, and I refer readers to my review of that for general information about this Society and its activities (review)

Like the previous Beethoven issue, the contents are based round composers, but, unlike that Beethoven one, it includes studio recordings as well as live ones. The idea of having all Mengelberg’s Mahler recordings in one place is a sensible and handy one, and necessitated the inclusion of the studio recording of the Adagietto from the 5th Symphony.

This famous recording of the Adagietto hardly needs any introduction from me; it confirms what is clear from other recordings by pupils and friends of Mahler about the tempo of the movement. At 7.12, (with Bruno Walter’s 8.05 in 1938 and 7.35 in 1947 recordings) as opposed to, for example, the 11.13 of Bernstein’s VPO studio recording, these timings are convincing circumstantial evidence of Mahler’s intentions. I must confess, however, that I am sufficiently a child of my time to prefer the Bernstein approach. Almost as important as the timing, to me, is the use of portamento. The almost complete absence of this in pretty well every modern recording is just as serious a falsification of Mahler’s expectations.

At least as important as an historical document is the performance of the 4th Symphony. Mengelberg was a friend of Mahler and did more than any other conductor before WW2 to keep his music before the public. In May 1920, as part of the celebrations marking the 25th anniversary of his conductorship of the Concertgebouw, Mengelberg conducted a nine-concert Mahler Festival in Amsterdam which included all the symphonies, Das Lied von der Erde, Kindertotenlieder and Das Klagende Lied. Mengelberg had previously invited Mahler to conduct the Concertgebouw ten times between 1903 and 1909, with programmes which included the 1st, 2nd,3rd, 4th, 5th, and 7th Symphonies and Das Klagende Lied, including one occasion on 23 October 1904 when Mahler conducted his 4th Symphony twice in the same concert. It was said by Alma Mahler that Mahler conducted one performance and Mengelberg the other, but I have the programme for this concert (and is also confirmed in Knud Martner’s Mahler’s Concerts listing) showing that Mahler conducted both. What is particularly relevant to the recording issued here is that Mengelberg attended all the rehearsals for this concert, making detailed notes in his score of what the composer did. This was something that Mengelberg was famous for – his conducting scores had so many markings in them that the printed text was almost obliterated (there is a remarkable photograph in the booklet for the WMS Beethoven set of the first page of Mengelberg’s score of Beethoven’s 9th Symphony). This is again, it must be admitted, circumstantial evidence, but I find it impossible not to believe that what Mengelberg does in this performance must be more closely reminiscent of what Mahler himself did that anything else we have. I don’t intend to go into detail about the performance, but simply to say that I find it entirely convincing, and in the places where the rubati seem extreme, this is perhaps more to do with modern expectations than anything that a contemporary of Mahler’s might have found extraordinary. Probably the most famous example is the ritardando in the third bar of the first movement. This is marked “grazioso. Etwas zurückhaltend” (“gracefully. Somewhat held back”), so a slowing-down is clearly indicated, but “somewhat” is one of those weasel words that can mean very different things to different people. Whether it works or not is an entirely personal reaction – as long as you don’t imagine (and demand) that your personal taste is the only possible way it can be. Jo Vincent, though slightly past her considerable best by 1939, makes a lovely job of the solo part in the last movement.

The final Mahler work in this set, Lieder eines fahrended Gesellen, is a much less well-known recording, and less interesting as the conductor’s role is much less important than the singer’s. Mengelberg’s conducting is detailed, but Hermann Schey is unfortunately not a particularly distinguished singer. His way of moving between notes is imprecise, and rather too often he doesn’t quite hit his destination accurately. Nor is his attack all that it should be; he constantly scoops up onto notes for no very obvious interpretative reason, adding to the rather clumsy, ungainly effect. He is at his best in the overtly dramatic first part of the third song “Ich hab’ ein glühend Messer”, but in the second half his legato is not good enough. Schey does not give a bad performance, but neither does he offer anything to raise it above the ordinary.

For the final two pieces we move to Mahler’s longer-lived contemporary, Richard Strauss. The first of the two tone poems is Tod und Verklärung, a Telefunken studio recording which is one of the less-frequently re-issued of the series. Like Mahler, Strauss was one of the great conductors of his day, and was an admirer of Mengelberg, dedicating Ein Heldenleben to him and the Concertgebouw. To be honest I’ve always found Strauss’s own recordings of his music disappointing. He seems to me to be a conductor entirely without sensuality, and I think that is an essential aspect in a great Strauss conductor. This performance is excellent, being full of inventive and convincing detail. After he had composed the music, Strauss got his friend Alexander Ritter to write a poem which made the programme explicit, and this performance reflects exactly the specifics in that poem. The halting rhythm at the beginning of the piece portrays the faltering heartbeat of the dying man after “mit dem Tod wild verzweifend noch gerungen” (struggling in wild despair with death) and Mengelberg’s phrasing of the oboe theme catches his exhaustion perfectly. The solo violin’s sweetness conveys the man’s memories of childhood – perhaps the portamento is somewhat sentimental, but would that not be an understandable emotion here? Mengelberg’s fluid approach to tempo is ideal for the gradual unease and panic as the man feels the resurgence of death’s attack, perfectly capturing the ebb and flow of his situation. After an “ensetzenvolles Ringen” (horrific struggle) where “keiner trägt den Sieg” (no one wins), he falls back exhausted, his mind again going to childhood memories, including “des Jünglings kek’res Spiel” (the youth’s cheeky play), which Mengelberg’s perky articulation catches exactly. The struggle returns to reach its conclusion, the man making a final rally, telling himself “Mach die Schrank dir zur Staffel! Immer höher nur hinan!” (make the barrier your step! Only climb higher and higher) with horn fanfares very reminiscent of Ein Heldenleben. The alternation of death’s attack in the brass with the man’s struggle against them in the strings is another place where Mengelberg’s fluidity allows him to characterise precisely. But the struggle is lost, and the man’s soul leaves his body in the rising scale on strings and woodwind followed by the quiet strokes of the tamtam, and the Verklärung (Transfiguration) section begins. There are two ways of approaching this: the usual one is what I think of as the Apollonian option, all white marble Greek temples and togas, a parallel to what Hesse called in Steppenwolf “the cold, clear laughter of the Gods” – a place where all is reason and calm, where passionate emotion has been left behind; this is the approach that Strauss himself takes in his recordings of the piece. The other might be called the Dionysian: a place of ecstatic, sensual fulfilment; the apotheosis of emotion rather than its negation. It will hardly come as a surprise, I think, that Mengelberg is firmly in the Dionysian camp. He paces the crescendo, both dynamic and emotional, superbly to the climax. But, of course, the piece does not end at that climax, and the final three repetitions of the Transformation theme in the strings which follow show a conductor’s approach particularly clearly. For the Apollonian conductor, these repetitions become increasingly purer and more ethereal; for the Dionysian they become increasingly sensual and ecstatic. The supreme example of the latter, to my knowledge, is the 1934 Stokowski recording with the Philadelphia Orchestra, where the final repetition has a simply astonishing full-blooded octave portamento – it’s the aural equivalent of Rosetti’s Beata Beatrix or Bernini’s Ecstacy of St. Teresa. Mengelberg doesn’t go quite as far as this (and, indeed, neither does Stokowski in either of his other recordings, from 1942 and 1944), but it is very definitely from the same stable (incidentally, I know which sort of heaven I want to go to when I shuffle off).

For Don Juan we are back with a live concert performance from 1940. I reviewed the recent Pristine re-issue of the 1938 Telefunken recording of this piece in detail (review) so will not repeat myself here, except to say that if anything this live performance is even finer, with greater characterisation and momentum.

I was full of praise for the transfers in the previous WMS Beethoven issue, and feel much the same about these transfers. The Adagietto from 1926 is, I feel, a little over-processed. There is no surface noise whatever, but I feel the sound is a little tubby, and slightly prefer the old Pearl transfer by Mark Obert-Thorn. This has a light rustle of surface noise, but the sound is a little more open and natural. I’ve always thought it was a pity that Mengelberg didn’t postpone recording this piece for a couple of years, when he would have had a more realistic string tone and a wider dynamic range. Both transfers manage the very awkward side join superbly. The 4th Symphony is excellent. Unfortunately I don’t have the Pristine transfer to compare it with, but it is markedly better in every way than the Philips transfer on CD from 1995. There is almost none of the fuzziness on the strings when playing complex or loud passages and all the irritating little ticks and plops from the original glass-based acetates have disappeared. The only Lieder eines fahrended Gesellen transfer I had prior to this one is on an old LP set from Music and Arts, and, unsurprisingly, this CD set is much better in every way. Tod und Verklärung is an excellent transfer. This recording is on the latest volume of Pristine’s Mengelberg Telefunken series, and I hope to be able to compare the two when that arrives – I expect there to be little in it. The live Don Juan is in simply spectacular sound; it could pass for a commercial recording from the mid-1950s.

So this set is just as fine as, and historically even more important than, the previous Beethoven set, with transfers to match or improve on any others.

Paul Steinson

Availability: The Willem Mengelberg Society