Déjà Review: this review was first published in September 2002 and the recordings are still available.

Benjamin Frankel (1906-1973)

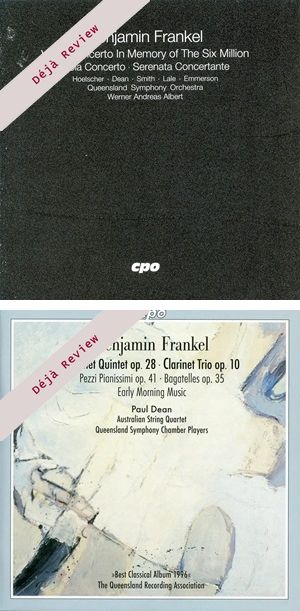

Concertos

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op 24 In Memory of the Six Million (1951)

Viola Concerto, Op 45 (1967)

Serenata Concertante for Piano Trio and Orchestra, Op 37 (1960)

Queensland Symphony Orchestra/Werner Andreas Albert

rec. 1996, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Brisbane, Australia

cpo 999 422-2 [66]

Benjamin Frankel

Chamber Music with Clarinet

Quintet for Clarinet and String Quartet, Op 28 (1956)

Trio for Clarinet, Cello and Piano, Op 10 (1940)

Pezzi Pianissimi for Clarinet, Cello and Piano, Op 41 (1964)

Bagatelles for Eleven Instruments (Cinque Pezzi Notturni), Op 35 (1959)

Early Morning Music (1948)

Queensland Symphony Chamber Players

rec. 1995, Australian Broadcasting Corporation, Brisbane, Australia

cpo 999 384-2 [58]

Benjamin Frankel has at last been artistically and critically rehabilitated, virtually single-handedly, by the sterling work of German record label Classic Produktion Osnabrück (cpo) and the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Apart from the publicity generated by Ken Russell’s not so recent Classic Widows feature (the soundtrack on Chandos is highly recommended), Frankel’s posthumous reputation, until cpo took up his cause, had seemed to lie almost exclusively with his, admittedly classic, film scores (Battle of the Bulge etc.). Now, with a significant body of work available on CD, he takes his place within what I would regard as the long overdue acceptance/appraisal of a “third stream” of 20th century British classical music. He stands alongside, for example, Humphrey Searle (also being recorded by cpo), Bernard Stevens, and, more recently, Alun Hoddinott.

It seems reasonable, without resorting to cliché and gross generalisation, to suggest that there was a substantial group of composers who shared little in common with the received nostalgic tradition embodied by Elgar or the mature Walton and perhaps Bliss. Nor with the folk/pastoral idylls encountered in Vaughan Williams, Finzi and Moeran. The music of many of these second Viennese school inspired figures has remained, until very recently, obscure, neglected and poorly regarded. Searle’s works were once (unjustifiably and certainly unhelpfully) described as being “like listening to the music from Star Wars played backwards through a washing machine”. The critical tide has changed in recent years though and the most recent Penguin Guide praises Hoddinott for using serial techniques as “a spur rather than a crutch” and for his “allegiance to tonal centres”. Both these comments are equally applicable to Frankel and are not a bad starting point for an appreciation of his muse.

Readers who have been directed to Frankel by Rob Barnett’s recent surveys for Musicweb of the complete symphonies and string quartets may be gratified to know that there is indeed more of his music available from the same high quality source. Both the discs reviewed here have been around for a while but are both stunning testaments, in their different ways, to the neglected genius of Benjamin Frankel.

The solid black booklet cover and the subtitle of the Violin Concerto may not bode well on the face of it, but this disc is absolutely not one concerned with unmitigated sorrowing. In fact, Frankel does the “memory of the six million” proud by producing a work of defiant, scurrying but lyrical energy. Only in the slow movement, would anyone guess the possible subject that inspired this piece. Despite the fact that this is pre-”fully serialised” Frankel, the most obvious reference piece is Berg’s marvellous concerto. Frankel’s is, surprisingly, less elegiac but no less moving or eloquent and comparison with the Berg or indeed the much more popular equivalent pieces of Britten or Walton does him no disservice.

The Viola Concerto, in itself a member of a relatively rare breed, is later and from Frankel’s overtly serial period but, true to form, he confounds expectation by introducing it with a long, complex but non-serial movement. The whole piece is, if anything, more lyrical (an overused but defining term for Frankel’s music!) and, surprisingly, more emotional than the Violin Concerto and is a wonderful, and often beautiful advert for an often overlooked instrument, the composer and without question the performer.

The disc is completed with a lighter concertante work (but ironically also the most “serial” on the disc). It touches on Frankel’s jazz band past, playing with, for instance, Henry Hall (of Teddy Bears Picnic and VW Partita fame!), and ends the proceedings on a definite upbeat, although the CD as a whole is hardly the morbid wallow the uninitiated might have expected. These ears found it a much easier proposition than, say, the late, also “serial” works of such popular figures as Copland or Stravinsky.

The disc of clarinet based chamber ensembles offers music of great distinction. The Quintet, written for Thea King and previously recorded on a mixed composer Hyperion disc, has been described as a masterpiece. I would not tend to disagree with that assertion although, despite its undoubted lyricism (there I go again!) and deft construction, it would be disingenuous to imply that it is in some way “easy listening”. Nor even as immediately accessible as, say, the equivalent pieces of Brahms, Howells or Bliss. The earlier Trio is also vintage Frankel, pre-serial, of course, here, but profoundly melodic (like everything on this disc and fully supportive of his view that “Melody is the ineluctable stuff out of which music is constructed”). The two short sequences of pezzi that follow reveal some memorable tunes and are beautifully put together, whereas the Early Morning Music is a humorous, “pop” inflected, and very enjoyable throwaway end to a great disc.

All the cpo Frankel discs are beautifully played and recorded, cover art is well-chosen and the booklet notes, by the very knowledgeable Buxton Orr (himself a composer who died several years ago) and E D Kennaway, are exhaustive and most clearly a real labour of love. What are you waiting for? Go and sample as a matter of urgency. A composer for whom exposure to Delius and Bartók represented a turning point is clearly someone out of the ordinary. Why then be surprised at a tonal serialist for whom melody was the thing?

Neil Horner

Concertos:

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Chamber Music:

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site

Performers

Concertos:

Ulf Hoelscher (violin – concerto)

Alan Smith (violin – serenata)

Brett Dean (viola)

Stephen Emmerson (piano)

David Lale (cello)

Chamber Music:

Paul Dean (clarinet)

Australian String Quartet

Markus Stocker (cello)

Kevin Power (piano)

Duncan Tolmie (oboe)

Leesa Dean (bassoon)