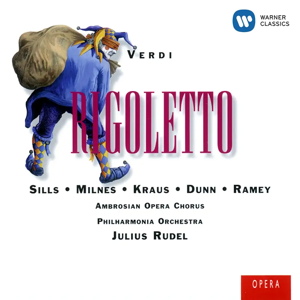

Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901)

Rigoletto (1851)

Rigoletto: Sherrill Milnes (baritone)

Duke: Alfredo Kraus (tenor)

Gilda: Beverly Sills (soprano)

Monterone/Sparafucile: Samuel Ramey (bass)

Maddalena: Mignon Dunn (mezzo)

Ambrosian Opera Chorus, Philharmonia Orchestra/Julius Rudel

rec. 1978, Studio No.1, Abbey Road, London, UK

Warner Classics 9029573588 [2 CDs: 117]

The merits of this forty-six-year-old recording come into sharper focus with the passage of time and the fact that there is such a dearth of really stylish interpreters of Verdi’s music in this current decade. Julius Rudel’s 1978 studio recording has always tended to sit among the shadows of the efforts by Giulini (DG), Bonynge (Decca) and Sinopoli (Philips). The aforementioned sets are all fine recordings with a great deal to commend them to the listener. However, hearing this set after a hiatus of several years leads me to conclude that it has been seriously underappreciated.

Julius Rudel brings a steady hand to the score which is given a dramatically taut reading that retains a sense of power and tension throughout the opera, even in the more relaxed passages such as the Act One love duet. He does not neglect the bel canto sensitivities of Verdi’s riveting score but neither does he emphasize them as much as Giulini and Bonynge do on their respective sets. He sets a good example in a feverishly intense account of the Prelude, which delivers an overwhelming impact at the climax. Both Giulini and Bonynge display this tension but in a milder fashion. Another place this is in evidence is in the lead-up to the storm trio of the Third Act; all three recordings are excellent but Rudel drives the tension just that little bit further.

EMI assembled a cast with three star singers (and one rising star) to tempt the record-buying public of that era. Sherrill Milnes’ jester was already familiar from his assumption of the role in 1971 for Richard Bonynge, where he was already a star singer in his prime, singing one of his best roles. The succeeding seven years finds his portrayal had gained a wealth of dramatic detail to achieve a high-octane performance which is more febrile than his earlier reading for Bonynge. Such passages as the taunting of Monterone (he sounds truly nasty here), or the increasing panic of his cries for Gilda at the conclusion of Act One are details to treasure. His voice is still in fine shape, firmly resonant with the capacity for tonal beauty in his more tender exchanges with his daughter. He and Rudel combine their talents for a version of “Cortigiani, vil razza dannata” which erupts with a volcanic power that is rarely encountered these days.

Alfredo Kraus is to my ears the most boyishly charming Duke on any recording that I have heard. This is quite a feat for a singer who was nearly 51 at the time of the recording sessions. He sings the role with a stylish elegance that few others can muster. “Questa o quella” is a perfect example of the taste and veracity of his performance. Little inflections of parlando effortlessly alternate with his sunny vocalizing. Indeed his Duke is almost too boyishly charming for the darker side of the role. The beauty of the supremely graceful line he commands in “Parmi veder le lagrime” is capable of dissolving granite. His age is evident only in that some of his upper notes emerge with a dryness to his sound that one doesn’t encounter on his earlier recording for Solti (RCA). His was not a powerhouse voice so the Duke brings him to the limits of his volume: it is worth noting that the engineers resist pushing up his microphone levels to artificially increase his vocal presence in some of the ensembles. This was the right decision to make in my opinion. While Luciano Pavarotti’s ebullient, jovial Duke is well-nigh a perfect assumption of the role, I find that Kraus’ winning characterization and vocal elegance steals away my preference for the Spanish singer over the Italian superstar.

Beverly Sills was 49 when she made this, her final complete opera recording. There is no disguising the fact that some of her upper voice was showing the signs of decline. Often her forte notes above G sound as if they are fraying at the edges, although there are times when they emerge with admirable clarity too. Despite that handicap, much of the time her singing is fresh, with her tone conveying a real impression of girlishness; more so than several of her rivals on other sets. Her coloratura is, as always glitteringly accurate, with an admirable sense of weightlessness. She pairs thrillingly with Kraus in the love duet; the two singers sail effortlessly through the difficult final cadenza which has often been cut because it is so challenging for the singers to bring off effectively. It is for me one of the measuring points for any performance of Rigoletto.

Samuel Ramey is a powerful and luxurious-sounding Monterone, in every way the equal of Kurt Moll’s powerhouse reading for Giulini. It becomes impossible to choose between them as to which is the more effective. However, having Ramey also sing Sparafucile on the same set is a questionable decision here. Ramey sings with his customary style and plush-sounding tone, but his vocal person is too alike to his Monterone and he ultimately he comes across as far too noble-sounding a gentleman for the riverbank assassin. Nicolai Ghiaurov, Robert Lloyd and Martti Talvela are all more able to convey the essential roughness of the character.

Mignon Dunn’s Maddalena is a thoroughly professional performance from a singer who was too little recorded in her day. I like the ironic laughter she conveys in her contribution to the quartet. EMI’s original LP set included an appendix aria that Verdi composed for Maddalena for an 1851 Brussels production which used to appear in all French vocal scores and libretti by the publisher Escudier, “Prends pitié de sa jeunesse”. On the album it was sung by Dunn with a piano accompaniment, and there is no clue to whether the aria reached past the rehearsal stage in France or anywhere else. Sadly, it was left out of the CD release, and the recent Warner digital download version. Warner could do a great service by making it available once again.

The recording quality of this set is of a reasonably high standard for its day. I find the perspective of the offstage chorus in the third act to be the perfect combination of distance while retaining enough clarity for the various choral parts to register to the listener. All in all, this recording has more going for it than its reputation credits it. It achieves a powerfully dramatic experience of one of Verdi’s finest works. The noted flaws among the cast do register, but not enough to sabotage the overall experience.

Mike Parr

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.

Other Cast

Marullo: John Rawnsley (tenor)

Borsa: Dennis O’Neill (tenor)

Count Ceprano: Malcolm King (bass)

Countess Ceprano: Sally Burgess (mezzo)

Giovanna: Ann Murray (mezzo)

Page: Jennifer Smith (soprano)

Herald: Alan Watt (baritone)