Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2005 and the recording is still available.

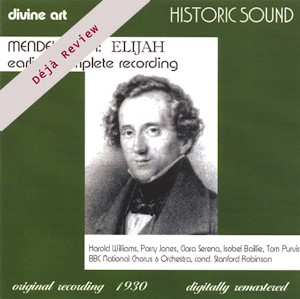

Felix Mendelssohn (1809-1847)

Elijah Op.70 (1846)

Isobel Baillie (soprano)

Harold Williams (baritone)

Clara Serena (contralto)

Parry Jones (tenor)

Tom Purvis (tenor)

Berkeley Mason (organ)

The Wireless Singers

BBC National Chorus & Orchestra/Stanford Robinson

rec. 1930, Central Hall, Westminster, London

Divine Art DDH27802 [2 CDs: 93]

Full marks to The Divine Art for digging out and dusting down this 1930 Elijah. There are cuts, it’s true, the majority in the second part but the words “substantially intact” certainly cover it and the exigencies were doubtless necessary at the time. The recording, made on 10″ discs not 12″, stayed in the catalogues for the better part of two decades until it was pensioned off in favour of the new Columbia album directed by Malcolm Sargent. Indeed whilst that recording has garnered great praise over the years and reissues – rightly so – this earlier set, conducted by the young Stanford Robinson, has been pretty well entirely obscured. Obscured and also confused, because the two principals, Harold Williams and Isobel Baillie reprised their roles seventeen years later for Sargent. Many may be unaware of their earlier contributions to the 1930 recording.

It’s a feature of Elijahs that the best were invariably Australian. Elgar always maintained that Horace Stevens was the greatest he’d ever heard but Harold Williams must have run Stevens close. In the early post-War recording he is in even greater form, utterly commanding, fiery and sympathetic, an assumption both noble and deeply human. But his earlier recording finds him only slightly less exalted. His recitatives are commanding and perfectly judged, Lord God of Abraham taken with great understanding and vocal colour and It Is Enough finds him contrasting a hollow expressivity with a central section of hardened determination where the resignation and dynamism are held in perfect equipoise.

Isobel Baillie is heard in youthful voice but then, when wasn’t her voice youthful and fresh? It’s a relative matter with Baillie and I can’t decide which of her performances, the 1930 or the 1947 I prefer; fortunately we have both. Her crystalline, dead-centre-of-the-note purity, with limited vibrato but compelling musicianship is audible throughout. She’s superb in duets, whether with Williams or the other Australian cast member – half the great singers in England before the War were Australian – Clara Serena. Baillie’s standouts are Hear ye, Israel and the perfectly posed blending of voices with her other principals. Serena, an alto, has a voice that is capable of some plangency but also relative lightness. It’s certainly not at all marmoreal and is a decided asset here – try her Part One aria For He shall give him Angels.

Parry Jones is the tenor, Obadiah, and he makes a real impression. He wasn’t a lyric tenor in the Nash mould or a heldentenor à la Widdop but he had something of Tudor Davies’ passion whilst exercising greater control over material. His If With All Your Hearts is done with real vibrancy and incision but also great musicality. The little known Tom Purvis also impresses in his short contributions. The orchestra is anonymous but doesn’t sound like a generic pick-up band at all. In fact for London in 1930 it’s pretty good, and the fiddles, whilst not sounding numerous, are well drilled and in the main abjure portamenti. The Wireless Singers were one of the leading choirs in the country; a select group they belie the English Oratorio Tradition of massed Henry Wood thousands and sing with considerable nuance and commendable control. Robinson shows, even in this somewhat abbreviated fashion, just what a dependable and adept conductor he was. If some speeds seem on the frisky side that may be a feature of the 10″ side lengths – but it’s also no bad thing to hear Elijah chug along this fluently.

Engineer Andrew Rose outlines some of the difficulties he encountered in the transfer and the solutions he adopted to minimise them. I don’t have the original 78 set nor do I have any subsequent re-issue (if there has been one) of parts of them on LP; an EMI LP included part of Parry Jones’ contribution in a tribute album. What I do hear is a degree of shellac crackle on some sides but uncompromised upper frequencies; an open sound that preserves treble but which extracts some of the real dynamism embedded in the 1930 grooves and moreover captures the spectrum. It makes listening enjoyable and shows what Columbia engineers of that period could do. So, with biographical details and texts and a sure sense of style, I’d recommend this retrieval with pleasure. Add it to the Sargent and you’ll have a fruitful and complementary look at a special lineage in Elijah singing and playing. And above all else, above even Baillie, you’ll have a double dose of Williams, a magnificent colossus of an Elijah.

Jonathan Woolf

To gain a 10% discount, use the link below & the code musicweb10