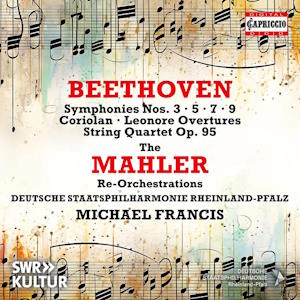

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

The Mahler Re-Orchestrations

Margarita Vilsone (soprano), Evelyne Krahe (mezzo-soprano), Michael Müller-Kasztelan (tenor), Derrick Ballard (baritone)

Czech Philharmonic Choir Brno

Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz/Michael Francis

rec. 2021-23, Ludwigshafen Philharmonie, Ludwigshafen Pfalzbau (9, live), Germany

Capriccio C5484 [3 CDs: 231]

Ah the deep dark rabbit holes of historical authenticity. With just about every major original work now urtexted and critically edited we are now entering the next level of being authentically inauthentic. After all, what is a Mahler edition of a Beethoven Symphony except for a late 19th century vision of an early 19th century work; “new improved Beethoven”? But, as the liner for this set makes perfectly clear, Mahler the conductor was in reverential awe of Beethoven the composer and everything he sought to do when performing the older master’s works was predicated on presenting them in the best possible light – as he perceived it. A significant part of that perception – and one that must surely have coloured his editorial choices (part doubling, voice transpositions and the like) – would have been the sound and technical adeptness of the orchestra(s) Mahler was working with. So, surely to present an ‘authentic’ representation of Mahler’s editions of Beethoven’s symphonies would require the orchestra in question to be playing in the manner of an authentic 1900 orchestra – an imitation of an approximation. Just recently there has been a release of Mahler’s own Symphony No.9 played “authentically” – would it be reasonable to expect the ‘sound’ of that orchestra to be grafted onto the performing edition here to attain the closest approximation to Mahler’s perceived aural soundscape?

Tellingly the very interesting liner note to this new set quotes Wagner expressing an opinion that held true through to Mahler’s extensive “Retruschen” [retouching]; “Sinfonia Eroica remains both a miracle of design and a miracle of orchestration. However, Beethoven requires a style of performance that no orchestra to this day has managed to deliver.” For “style” I suspect Wagner means technical ability and collective skill – something that is simply no longer an issue for professional orchestras – as this new set amply confirms. One other thing worth considering – just about any conductor past or present will tweak a score on some level or another. Certainly I imagine Mahler’s contemporary colleagues would come to orchestral rehearsals similarly armed as he – Sir Henry Wood’s performing sets of parts are covered with his famous blue pencil markings which allowed his hard-working Queens Hall Orchestra to churn out performances on minimal rehearsal because all the parts were pre-marked. Mahler’s enduring status as a composer is ultimately why his practical editing as a conductor is of interest today – but in all likelihood comparable work by say Arthur Nikisch or Hans Richter or Wood would be equally valid as an insight into performing practices of the day. Of course we do have a brilliant conductor who offers just such “retouchings” today – Manfred Honeck’s recordings in Pittsburgh for one are consistently revelatory, challenging and thought provoking while being respectful of the composer’s perceived intentions.

Mahler ‘retouched’ all of the symphonies except No.4 as well as five of the eleven overtures. The generously filled three disc set gives us four of the eight reworked symphonies and three of the overtures suggesting that there is possibly another two disc set to complete the survey. The opening paragraphs might lead readers to think that I have not enjoyed this set. Far from it – I found it to be genuinely fine – superbly played and thrillingly dynamic and indeed revolutionary – just as I suspect Mahler wanted us the listener to experience it. Not surprisingly I did start out listening to these performances trying to spot the tweaks and adjustments Mahler had made but very quickly that felt like a rather pointless and redundant exercise. Mahler was not seeking to place his own musical ego between the listener and Beethoven – again as the liner points out and these recordings triumphantly realise his goal was one of clarity. He sought to guide the listener’s ear to hear more clearly the true genius of Beethoven’s music. What we are given here across all three discs are thrillingly vital, powerfully dynamic and exciting performances by the truly excellent Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz under conductor Michael Francis.

The first disc is Beethoven at his most revolutionary – Symphonies 5 and 3. There are some features here that struck me immediately. Tempi are bright and alert – I have no idea if Mahler’s editing including metronome markings – but these have the lightness and sheer velocity that I would have associated with “historically aware” performances. For some reason I thought Mahler’s Beethoven might be heavier in the manner that we were led to believe the 19th century weighted these scores down. Likewise the orchestra play with an articulation and the strings with a lack of vibrato that the innocent ear would ascribe to modern HIP practices rather than late 19th century. The timpani are played crisply with hard sticks. I was surprised that the exposition repeat in the Eroica is omitted – did Mahler really cross that out? But then there are some passages that I cannot imagine being played as well ‘then’ as they are here. The meltingly beautiful oboe solo in the Eroica’s finale [track 8 around 6:00] is played with heart-breaking poise by the uncredited German player – but with no breaths. I am not sure rotary breathing was a technique available to Mahler’s players but it certainly is ‘better’ as here. The Capriccio recording is very fine too across all three discs – Symphony No.9 was recorded live while the other two discs were made under studio conditions in the ideally supportive but not overly resonant Philharmonie Ludwigshafen. Michael Francis’ conducting is energetic and exciting – I have to say this is how I like my Beethoven to be regardless of any editorial interventions. Once you understand that this is his preferred style nothing is particularly surprising or radical but it is all very effective and extremely well executed. By that measure alone it is not that unusual – Leibowitz’s famous Reader’s Digest cycle with the RPO from the early 1960’s is just as crisp and muscular so perhaps again a case of “everything old is new again”.

The only piece that did not ‘work’ for me at all was the string orchestra transcription of the Op.95 String Quartet in F minor which appears on the second disc of the set. Transcription is really overstating the case – as with his expansion of Schubert’s Death and the Maiden all Mahler does is some judicious doubling of the cello line by the double basses. The main interest lies in his adjusting of dynamics and phrasing. Mahler’s justification with the Beethoven is that the four players of a quartet alone – any quartet – could simply not embrace the ambition of Beethoven’s vision. My strong belief is that the genius of the original is precisely down to the limitations imposed by just those four essentially monophonic lines. The performance here is every bit as fine and well-judged as they are for the symphonies but the result is over-blown and excessive to my ear and not revelatory in the way that the symphonies can be argued to be. But then I do not enjoy Mahler’s Death and the Maiden either for the same reasons. Also on this disc is Symphony No.7. This receives a performance every bit as dynamic and dramatic as those on disc 1 but personally I am not sure that this approach is quite so effective for the work Wagner famously called the “apotheosis of the dance”. Of course the truth is the work contains some of Beethoven’s most extreme dynamic and expressive markings – ones which are clearly retained by Mahler and the Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz here. But perhaps it becomes fractionally unrelenting especially in the outer movements.

Interestingly the liner outlines the criticism that Mahler faced in the contemporary press for ‘daring’ to tamper with the Master’s great works as well as his justifications for so doing. But I wonder how many of the critics had a genuine insight into the pieces as they were originally performed and how many were tied to the performing conventions of their time which is precisely what Mahler sought to challenge. The final disc in this box includes a performance of a work that challenged convention from the moment it was first performed – the Symphony No.9 ‘Choral’. That being the case and also based on the scale and ambition of the original work I did wonder if this would be the work in which Mahler’s large-scale late Romantic sensibilities would be fully unleashed. Actually not at all, although a significant factor here might the change in performing context. As mentioned before, this symphony is recorded ‘live’. The playing remains remarkably fine – alert and precise and the Capriccio engineers have done an excellent job eliminating any audience noise [no final applause either] while preserving a very good balance and general soundstage across the entire orchestra, soloists and choir – although the timpani outbursts in the scherzo are slightly too spotlit. Whether it is a characteristic of the different recording environment or not, this performance is also the one where the lean, quite light and focussed string tone with minimal vibrato is particularly striking. Even allowing for the very fine collective and individual playing this comes across as a fairly ‘ordinary’ Ninth. Perhaps because the performance is live there is a slight sense of executional and interpretative safety rather than the boundary-exploring dynamism of the other studio-recorded symphonies in this set. The liner outlines some of Mahler’s added effects – doubling the horns to 8 and having a backstage orchestra enter with the famous building march theme from around 9:50 [track 5]. Certainly the orchestra sound quite distant here but I am not sure they physically ‘enter’ as Mahler envisaged. Sadly, the four soloists range from unexceptional mezzo to a rather woolly and unfocused baritone, forced and strained tenor and squally soprano. This solo quartet is quite close to being a deal-breaker in this performance. The Czech Philharmonic Choir of Brno are very good with the attack and focus that characterises many of the best Eastern European groups. Interpretatively Michael Francis is eminently sane and centrist – tempi never drag and are certainly never rushed but I was never gripped by this performance in the way that great versions can and likewise never challenged or intrigued as the others symphonies in this set did.

Distributed across the set are three of the overtures Mahler edited. The Leonore No.3 Op.72b which forms the coupling to the Ninth gets a very fine incisive performance that again underlines the slightly curious realisation that many of the stylistic choices enshrined in these Mahler editions are echoed by nearly all modern day interpreters – certainly on modern instruments – of this repertoire. The tricky passage work for the strings is executed with ideally neat nimbleness and clear articulations. Textures are kept transparent and tempi are energised and lively.

The liner booklet makes a good deal about the pushback Mahler received for his ‘tinkering’ with the master and generally the information about the works is helpful and quite detailed. What it lacks is specific information regarding instrumentation and performing changes that Mahler made to each work. Without being slavishly detailed a broad overview along with some key moments would have provided a valuable guide for the interested listener. Overall this is a very impressive set with Mahler’s respectful editions realised with enthusiastic and virtuosic panache by a clearly engaged Deutsche Staatsphilharmonie Rheinland-Pfalz. Certainly the success of the survey makes one hope that Capriccio will be inclined to complete the “Mahler Edition” of these symphonies with the same artists. Beethoven’s genius emerges triumphantly – which is surely exactly what Mahler intended.

Nick Barnard

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

Symphony No.5 in C minor Op.67 (1808)

Symphony No.3 in E flat major Op.55 ‘Eroica’ (1803)

Coriolan Overture in C minor Op.62 (1807)

Symphony No.7 in A major Op.92 (1812)

String Quartet in F minor Op.95 (1810)

Leonore Overture No.2 Op.72 (1805)

Leonore Overture No.3 Op.72b (1806)

Symphony No.9 in D minor Op.125 ‘Choral’ (1824)