Déjà Review: this review was first published in July 2009 and the recording is still available.

Johann Sebastian Bach (1685-1750)

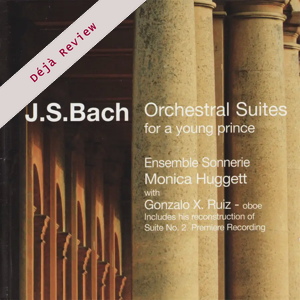

Orchestral Suites for a young prince

Ouverture No. 1 in C (BWV 1066)

Ouverture No. 2 in A minor (after Overture in B minor, BWV 1067; reconstruction: Gonzalo X. Ruiz)

Ouverture No. 3 in D (after BWV 1068)

Ouverture No. 4 in D (BWV 1069)

Ensemble Sonnerie/Monica Huggett

rec. 2007, Saint Silas Church, Kentish Town, London, UK

Avie AV2171 [74]

The four Ouvertures or orchestral suites by Bach belong to the most popular music of the 18th century. They have been recorded numerous times and one wonders whether it is necessary to add another disc to the large catalogue. The answer is: yes. What we have here is a performance of what is thought to be the original versions of the four Overtures. This means: no flute in the second suite and no trumpets and drums in the third and fourth.

The form of the overture-suite, as it is labelled by musicologists, has its origin in French 17th-century opera. It began with an overture in A-B-A form: a slow section in dotted rhythm is followed by a fast contrapuntal section after which the slow first section is repeated. French operas always contained a number of dances, and the performance of a sequence of instrumental pieces from an opera became quite popular. Thus the orchestral overture-suite was born. It was enthusiastically copied by German composers of the late 17th century who had a strong preference for the French style. In the early decades of the 18th century it became a common form in Germany, but it moved away from its specific French colour. As Reinhard Goebel, director of the former ensemble Musica antiqua Köln once said, most French wouldn’t probably have recognized such overture-suites as French.

There are different views among musicologists about when and where Bach composed his Overtures. Robin Stowell, in the Oxford Composer Companions’ volume on Bach, states: “Our principal sources are copies of the Leipzig period, some written or corrected by Bach himself, and recent research suggests that the works themselves, with the possible exception of no. 1, originated during the Leipzig years”. But not everyone agrees: Monica Huggett believes these works belong stylistically to Bach’s pre-Leipzig years. This explains the title of this disc: Ms Huggett and the oboist Gonzalo X. Ruiz both think these four Overtures were written in Köthen for the young Prince Leopold. Several Bach experts also believe the scorings of the Overtures 2 to 4 are reworkings of the original versions. Ruiz thinks only the first has come down to us in its original form. The second Overture should originally have been written for oboe – instead of flute – and strings, the third for strings only and the fourth for three oboes and strings.

In particular the second suite has been the subject of debate, and several experts have proposed alternatives for the flute part which is considered not very suitable for the transverse flute. Joshua Rifkin, for instance, suggested the flute part should be played on the violin, but Ruiz argues that this wouldn’t solve all problems. He presents the oboe as the most likely option. It is interesting to hear the Overture in this scoring. It changes the character of the piece considerably. It is far less galant than with the transverse flute which was becoming a fashionable instrument in the 1730s. In particular the last movement is quite different, as Ruiz writes: “The trumpet-like strains of the Battinerie (misspelled and therefore misinterpreted as Badinerie since Bach’s time) acquire a suitable martial mood, more battle than chit chat”.

The orchestra of Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Köthen consisted of strings, oboes, bassoon and harpsichord, and this is reflected by the scoring of the Overture No 1 as well as what is claimed to be the original scorings of the other three Overtures. The two last Overtures – and in particular the third – contain some differences in texture as well. Therefore these ‘original versions’ are more than just the well-known suites stripped of trumpets and drums. I tend to agree with Ruiz when he states that “[the] resulting loss of grandeur is more than compensated by the lighter more dancing character these works acquire in their original orchestrations”.

What about the actual results of this musicological research? When I started to listen to this disc I was slightly disappointed. I felt that the overture of the first suite was a bit flat and lacklustre, and that continued in the first dance movements. I had liked stronger dynamic accents, and I also felt that some tempi were a bit slow. It was with the bourrée I and II that I started to feel involved: the accents were a bit stronger and the playing was more energetic. But it could well be that these are my very personal experiences and that others feel quite differently.

The second suite is the most interesting: it is the first time I heard this work with an oboe instead of a transverse flute. Being not a musicologist I can’t assess the scientific arguments in favour of this scoring, but it seems unlikely they will put the debate to rest. I can only judge this version by listening to the performance on this disc. I must say that Gonzalo Ruiz’ own performance has won me over: his musical plea is eloquent and quite convincing, and the ‘battinerie’ is given a splendid performance.

The remaining two suites have been played and recorded in their original versions before, so they are less surprising. But I very much enjoyed the performances, which are truly engaging and energetic. The dance rhythms are well exposed, partly due to clear dynamic accents and an excellent articulation. The overture of the third suite is one of the highlights, as well as the Réjouissance which closes the fourth suite and brings this disc to an end.

There are a couple of question marks in regard to the treatment of the repeats, though. I don’t quite understand why in the dance movements of the first suite the repeats are always played with strings only, without the oboes. And why is this practice only applied in this suite, and not in the Overture No 4? Many movements have an A-B-A’ structure. There are two different ways of dealing with the repeats here. Most interpreters repeat every episode in the A and B sections, but perform the episodes in the A’ section just once. Others opt for a repeat of every episode: so in the A’ section all episodes are also played twice. Monica Huggett follows a third route in the A’ section: the first episode is repeated, the second is played once. I don’t see the logic of this; unfortunately the booklet doesn’t give a clue as to what the reasons are.

Despite these remarks I greatly appreciate these performances. This disc is indispensable for Bach aficionados, but more average music-lovers will certainly enjoy it as well because of the quality of the playing of Sonnerie and Gonzalo Ruiz.

Johan van Veen

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.