Déjà Review: this review was first published in June 2003 and the recording is still available.

Gustav Mahler (1860-1911)

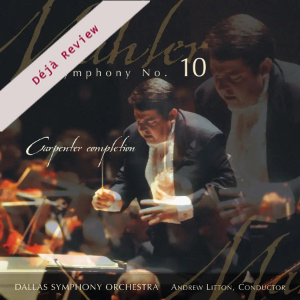

Symphony No.10 (1910-11, orchestrated and completed by Clinton A. Carpenter)

Dallas Symphony Orchestra/Andrew Litton

rec. 2001, McDermott Hall, Dallas, USA

Delos DE3295 [79]

It is possible that there are still a few people who believe the material for the uncompleted Tenth Symphony left by Gustav Mahler at his death should never be heard. If there are I disagree with them, as do most Mahlerians these days. Not to hear this music would be to rob yourself of insight into the crucial final year of a creative life cut short, as well as what can be a searing emotional experience. All that the listener then really needs to hear is a fully orchestrated performing version of the material that delivers, more or less, because this is never an exact science, what was left behind at the point that Mahler died. Deryck Cooke’s well-known and well-recorded version already does this admirably and I have yet to be convinced that anyone really needs to go further than a performance or a recording of the final version of Cooke’s score. There will, of course, be differences between each conductor’s performance of it and that is as it should be. So all that then remains for the record collector to choose is their preferred conductor. Rattle, Chailly, Morris, Levine and Inbal have all given subtly different renderings of Cooke’s score; more than enough to offer insights into this important music in Mahler’s output. No doubt there will be more in the future. Commercial versions from Wigglesworth and Harding would be most welcome going on past performances. For preference I would point you to Simon Rattle’s recording on EMI (review). Though I do hope EMI will see fit to re-issue at bargain price Rattle’s earlier Bournemouth recording.

That isn’t to say I would rule out listening to other people’s editions of the material altogether. I am as curious as the next Mahlerite. Joe Wheeler’s version is certainly worth a listen, especially now it is available on a fine bargain Naxos release conducted by Robert Olson (review).

Rudolf Barshai’s edition of the score also seems to have some interesting things to say if a broadcast of an early performance is anything to go by and a recording of that is expected. However I remain convinced that any variables between experiencing performances of this music really ought to be those that obtain between different conductors’ interpretations and for that the Cooke edition offers the best basis both intellectual and musical. For example that broadcast I heard of Barshai’s edition was more remarkable for his wonderful conducting rather than his own editing of the score, interesting and stimulating though that certainly is.

For decades all that was available to us in performance was the Deryck Cooke version, but in recent years two versions by Remo Mazzetti, that one already mentioned by Rudolf Barshai and also one by Niccola Sammale with Giuseppe Mazzuca have appeared. There may even be another in the works. Add these to the versions by Joe Wheeler and by Clinton Carpenter that always existed alongside Cooke’s but remained unperformed until recently and you see that the field is suddenly rather crowded. However, for any future editions let us be careful that we do not enter the shadow of the law of diminishing returns. I have heard all of these extant versions and, with one exception, I think that to the general listener there is not all that much difference between what Cooke gave us so memorably and all the others; nothing I could hear to make me want to replace Cooke’s version with any of them at the moment. There is certainly not enough to get in the way of telling me the direction in which the Tenth Symphony was heading when Mahler died and that must remain the benchmark. So the question has to be asked as to whether we really do need all these different versions of the score when there is more than enough in the Cooke version for conductors to get their teeth into.

I have a nagging feeling that many Mahlerites feel cheated by the fact that Mahler died young. In the dark watches of the night I confess to feeling it just a little myself. He was fifty, so his death must have robbed us of two or three more symphonies and other works. Could this be why some Mahlerites seize on anything Mahlerian that has any whiff about it of the “new” or the “not heard before”? Is this what is behind the absolutely baffling devotion some people have to the hideous chamber arrangements of the Fourth Symphony and Das Lied Von der Erde, for example, that are now gaining currency and which Mahler had absolutely nothing to do with? Likewise with new performing editions of the Tenth Symphony. When a new one appears it is almost as if, for some, an entirely new symphony has been discovered whereas all that has in fact been produced is a different take on what we have had all the time – a shift in perspective, no more than that. Just because someone is able to produce a performing version of the Tenth Symphony material does not necessarily mean that they should. If you only ever listen to the Deryck Cooke version of this work I do assure you that you are as close to Mahler’s Tenth as you are ever likely to be this side of heaven and you could leave it there with impunity for the rest of your days.

I mentioned earlier that, though versions of the Tenth material other than Deryck Cooke’s offer little fundamental difference from it for the purposes of knowing what Mahler was doing at the time he died, there was for me one exception. That exception is the score used on this recording. By beginning work in 1946 on the Tenth Symphony material Clinton Carpenter was the first in the field, many years ahead of Deryck Cooke. However it would be 1966 before Carpenter completed his score’s final edition, 1983 before it received a first performance and 1995 before it received a recording making it, in performance terms, later than Cooke’s. That recording was disappointing. Conducted in a perfunctory, cavalier fashion by Harold Faberman, the tone-starved, lacklustre orchestra seemed barely interested in the work so it was next to useless in illustrating what Carpenter had done with the music. This new Dallas version from Andrew Litton now proves that conclusively. But it also enables me to lay my cards on the table and say that I am now sure of what I had long suspected but felt able only to hint at in my Mahler recording survey; that Carpenter’s is not an edition of the Tenth Symphony I could ever live with or feel I could recommend to anyone else to live with either.

The problem is that it goes much further than the Cooke version in trying to “second guess” what Mahler might have done from then on rather than present what we have been left with in, more or less, acceptable performing trim which is what Cooke does with creative restraint. To put it bluntly, for me there is far too much Carpenter in here and, as you will see, I think he gets in the way, which can’t be right. Indeed it concerns me that there may be buyers of this CD, maybe new to Mahler, who on reading the label and seeing the word “completion” might feel that this is indeed how Mahler’s Tenth would, or might, have sounded had he lived to finish it himself. Clinton Carpenter is certainly a clever man, one of great integrity too, but I firmly believe that he not only presumes too much, in many aspects he is just plain wrong at the conclusions he reaches, in many cases to the serious detriment of the music. Unlike Cooke, by “crossing the line” into presumptive speculation through his publicly stated intentions, Carpenter does compel us to ask the crucial question as to whether this is indeed how the Tenth would have sounded had Mahler lived – a question we never really have to ask with Cooke. In fact a question that should never have to be asked at all. The answer to the question I arrive at is an emphatic no, and I believe I would be failing in my duty if I didn’t say this here.

Does any more need to be said about this new recording? Yes, I think it does. Andrew Litton has a track record as a good if, of late, a rather too fastidious conductor of Mahler’s music and he does perform this particular score with imagination, attention to detail, insight, and faith bordering on the zealous; far more than it deserves in fact. He clearly understands the significance of the Tenth in Mahler’s output. That much still comes through, even with this score getting in his and our way. His orchestra plays well and they are handsomely recorded. So what a pity these considerable efforts and talents were not put to better use on the Deryck Cooke score instead of being lavished and wasted on this one. I really do wonder why Litton is so enamoured of the Carpenter version. Someone with his obvious insights and affinities to Mahler’s music ought surely to have seen that Cooke’s score is a far superior, far more appropriate piece of work. His explanations contained in the liner notes seem to me somewhat diffuse and don’t really convince me, but I will not delve too deeply into those and deal with the recording as I hear it.

In the first movement Litton’s usual admirable care for detail means that he can luxuriate in the richness of textures that Carpenter offers him. But I think the two men combine to deliver a far too comfortable view of this music. There is great weight from the brass and percussion at certain nodal and crisis points that I think cushions the nerve-ends of music that really needs to be exposed in a starker and simpler relief in order to tell on our senses. Mahler was heading into a simpler style at this time. Right through the movement, and the whole symphony in this edition, there is always so much going on in a way that for me is fundamentally un-Mahlerian in one very crucial aspect. Mahler was a master of clarity of thought. Even in his most thickly scored passages the listener’s ear never has trouble following his fundamental line of thought. Whereas here, in Carpenter’s edition, over-scoring frequently prevents this for vast tracts of the music. The ear and the mind just lose track. Take the crisis that culminates in the long high trumpet note two-thirds of the way through the movement. The initial outburst here is just too deep and rich to penetrate our emotions. It is not searing enough, and the cymbal crash is surely too easy an option as well. However, it’s in the second movement that Carpenter’s over-scoring really kicks in disastrously and a generous reverberation in the recording doesn’t help matters much either. Mahler’s poisonous ländler now becomes blunted badly by the mannered and cluttered busyness of the orchestration and through we listeners trying to keep track of it all. Mahler himself would surely not have been so inept and gauche as this music makes him seem. He would have known what to leave out. Passage after passage is scored to the point of saturation and Litton delivers every jot and tittle of it with terrier-like tenacity. The same thing happens with the fourth movement that here becomes not much more than an orchestral showpiece. There is so much more going on at deeper and deeper levels that are obscured by Carpenter’s orchestral peccadillos. In Deryck Cooke’s version you may find this movement the least convincing of all. Maybe that is because Mahler himself hadn’t worked out how to deliver successfully that which he can only hint at in what he left behind. Therefore Cooke’s solution, relatively unsatisfying though it may be, is surely the more appropriate in the circumstances. The unfinished tower is better than one with a false roof and spire added by another architect from another generation. Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent, as another Viennese genius once wrote.

This problem of the over-loading of details in the orchestration carries on through the last movement in the same way. I also don’t like the treatment of the great lyrical melody. Litton’s conducting of Carpenter’s scoring comes over as saccharine and sickly. When it comes to the famous drum strokes at the start of this movement I have never been a supporter of those conductors who get their players to hit their instrument with all their strength. However even I think Carpenter’s decision to score the bass drum strokes as soft taps is wrong and this decision becomes truly disastrous in this recording at the return of the strokes further into the movement where they are virtually inaudible. These strokes are some of the most searing moments in all Mahler’s music and yet here they pass us by almost unheard.

To put it all at its starkest I am sorry to have to say that Mahler was simply not as bad a composer as Carpenter seems determined to paint him in this score. He seems to want us to view Mahler at this late stage in his life as a kind of “kid in a candy shop” determined to stuff himself full to bilious of every home-made confection he can see in front of him and to hell with the consequences. Mahler was never like that and to depict him thus does him disservice. Indeed I think this whole score does Mahler disservice. I think that in the words of composer and Mahler expert David Matthews it “distorts Mahler’s voice”. I certainly don’t think it adds anything to our knowledge of Mahler’s music that isn’t already dealt with by the Cooke version and if you do need an alternative to that in your CD collection there is the Wheeler score as conducted by Robert Olson on Naxos.

I don’t know what the Mahler Tenth would have sounded like had Mahler lived and I will never know. But I am sure it would not have sounded like this. But these are the opinions of just one person, one Mahlerite with some experience. I hope that another review of this recording can appear here on Music Web to give another opinion. It may even conflict with mine, but I will hold to my opinion nonetheless.

If you must have this curio in your collection then this is clearly the recording for you as it is the only recording available. I hope it stays that way.

Tony Duggan

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free