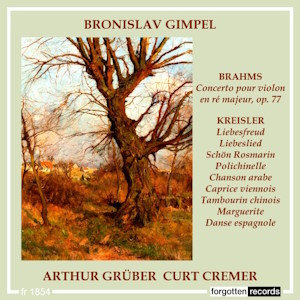

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Violin Concerto in D, Op. 77

Fritz Kreisler (1875-1962)

Pieces for violin

Bronisław Gimpel (violon)

Orchestre Symphonique de Berlin/Arthur Grüber

Orchestre Pro Musica, Stuttgart/Curt Cremer (Kreisler)

rec. 1960 (Brahms); 1958 (Kreisler)

Forgotten Records FR1854 [69]

Bronisław Gimpel (1911-1979) was never signed up by a major label and, as a consequence, his legacy has taken something of a backseat. It was a career that was multi-faceted, embracing the roles of soloist, concertmaster, chamber musician, teacher and conductor. Born in Lemberg, now known as Lviv, a city in western Ukraine, his first teacher was his father. At the age of eight he enrolled at the Lwów Conservatory to study with Moritz Wolfstahl. By eleven he’d progressed sufficiently to begin studies at the Vienna Conservatory under the tutelage of Robert Pollack, who was Isaac Stern’s early teacher. Later, Gimpel spent about a year with Carl Flesch at the Berlin Hochschule für Musik, yet never attained the acclaim of the pedagogue’s most famous pupils, who included Henryk Szeryng, Ida Haendel, Ivry Gitlis and Ginette Neveu. Flesch advised him to get some orchestral experience, and Gimpel spent time working under Herman Scherchen in Königsberg and Otto Klemperer in Los Angeles. He then went on to pursue a solo career. He founded the Warsaw Quintet, and later the New England String Quartet in the States. Between 1967 and 1973 he taught at the University of Connecticut. Other teaching posts included a spell in the 1970s as a professor at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester, UK. He returned to his remaining family in Los Angeles in 1978 and died a year later aged only sixty-eight.

The Brahms Concerto is exceptionally fine. It’s a recording where all the best qualities of Gimpel’s artistry shine through. The conductor Arthur Grüber must take some of the credit too. He sets the tempo in the opening tutti at an agreeable pace. Gimpel responds to Grüber’s sensitive support with phrasing and articulation carefully considered. His technical command is flawless and his intonation dead of centre. He employs Kreisler’s cadenzas throughout. The slow movement is fervent and heartfelt, with the opening oboe solo beguiling and tender. The Hungarian finale isn’t short of fire and gusto either. There’s an ideal balance struck between soloist and orchestra.

The violinist next performs a selection of Kreisler sweetmeats. These are more commonly heard with piano accompaniment, so it’s a novelty to experience them with orchestra. Gimpel is here partnered by the Orchestre Pro Musica, Stuttgart under the direction of Curt Cremer. The performances, consisting of Kreisler originals and arrangements, are taken from a late 1950s Vox LP. Gimpel plays these charmers with zest, warmth and a tempered brushing of schmaltz. Tambourine Chinois is one of the best. The virtuosic sections alternate with a suave, elegant double-stop melody of winning seduction. Marguerite, after a Rachmaninov “Romance” has a hint of wistful regret, whilst Liebeslied has all the Viennese swagger you could ask for. In fact, all of these pieces are played with elegance, style and panache.

Stephen Greenbank

| Availability |  |

Liebesfreud

Liebeslied

Schön Rosmarin

Polichinelle

Chanson arabe

Caprice Viennois

Tambourin Chinois

Marguerite

Danse Espagnole