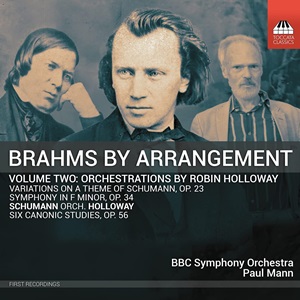

Brahms by Arrangement Volume 2

Orchestrations by Robin Holloway (b. 1943)

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Variations on a Theme of Schumann, Op 23 for piano duet (1861, orch 2016)

Robert Schumann (1810-1856)

Six Canonic Studies, Op 56 (1845, arr for two pianos by Debussy (1891), orch 2011)

Johannes Brahms

Symphony in F minor, Op 34 (1864, orch 2008)

(After the Sonata for Two Pianos, Op 34a)

BBC Symphony Orchestra / Paul Mann

rec. 2022, Studio MV1, BBC Maida Vale Studios, London

Toccata Classics TOCC 0450 [85]

When I saw that this Toccata release was labelled Volume 2, I scratched my head; I couldn’t remember its predecessor. Some searching through MusicWeb revealed that Volume 1 was very warmly received by my colleague, Nick Barnard, as long ago as 2012 (review). That disc contained two chamber works. One was the composer’s own arrangement of the Clarinet Quintet, Op 115 for double viola quintet. The other work was the String Quintet in F minor Op 34 (1862) in a conjectural reconstruction made in 2006 by Anssi Karttunen; the latter work is relevant to this present disc.

The booklet accompanying this latest release includes two extremely interesting essays. One is by the composer Lloyd Moore, who discusses the way in which, over time, music of the past has come to have more and more of an impact on Robin Holloway’s creative output. Moore’s essay is most valuable, but the other one is even more helpful; it’s by Holloway himself, and in it he discusses the three works by Brahms and Schumann which Paul Mann and the BBCSO have recorded.

The background to Op 34, as outlined by Holloway, is especially fascinating. Its original incarnation is as the String Quintet, Op 34 (1862). Brahms then reworked the music into a Sonata for Two Pianos, Op 34a (1863-64). A third version was made for piano and string quartet Op 34b (1864). In Holloway’s view, it’s the two-piano version which is the most successful; he comments that “the ‘en blanc et noir’ medium suits the granitic severity of the music”. His orchestration of the two-piano version of Op 34 represents the fulfilment of a long-held ambition: he first did some work on the introduction to the finale in the 1970s, but it wasn’t until 2008 that, in diary terms, the stars aligned, allowing him the time to work on the score as a whole and in detail.

I think I should quote what seems to me to be a telling remark in Holloway’s essay: “my version is faithful in spirit not letter. There is no attempt to remain within the confines of Brahms’ own practice, nor of the instruments, and their technique, of his day. It is neither what he himself would nor could have done, though it eschews self-expression in the cause of enabling, I hope, this magnificent music to be more completely itself”.

The precise scoring of Holloway’s orchestrated version is not specified. However, I infer from what I hear and from comments in his notes that he uses what I might call a typical Brahms orchestra with the addition of cor anglais and contrabassoon. Perhaps the most celebrated example of an orchestration of a Brahms work is Schoenberg’s orchestration of the G minor Piano Quartet. I admire a lot of what Schoenberg did in that score, but I’m afraid I completely part company with him in his extravagant use of percussion such as the xylophone and glockenspiel. I was mightily relieved to read that Holloway, while not criticising Schoenberg, feels percussion would be “preposterous” in this instance, given the nature of the music in Op 34. As I listened to Holloway’s reimagining of Brahms’ music, I frequently jotted down in my notes instances where the colourings he adopts have a distinctly Brahmsian feel. Especially through his use of the woodwind and through the way lines are given to the strings. It’s important to say, though, that what Holloway has produced is no mere Brahmsian pastiche. Indeed, there were a few occasions when I wondered if Holloway’s use of the trumpets wasn’t in line with what Brahms would have done (at 2:57 in the first movement, for example and later when the same material is reprised just after 7:00). But then I reasoned that Holloway is not giving us a Brahms copy but rather his own take on the music in the spirit of Brahms.

The first movement of Op 34 is a big movement in every sense – here it plays for 16:06 in a work that lasts in total for 44:08. Brahms’ music in this movement is symphonic in character and reach; Holloway’s orchestral scoring confirms the symphonic stature of the movement. The two inner movements – an Andante and a Scherzo – are imaginatively and idiomatically scored. In the Andante, the woodwind instruments and the strings are able to produce long, singing lines in a way that two pianos would not have been able to match in Op 34a. In the Scherzo, the involvement of timpani – though not to excess – helps to underline the driving rhythms. At around 3:00 in this movement I noted punchy writing for horns and brass which, dare I say, is more Holloway than Brahms – but it works. The Poco sostenuto introduction to the finale has good tension thanks to the sustained orchestral lines. Brahms made the music in the main body of the movement, marked Allegro commodo (from 1:44), full of incident anyway, but Holloway’s imaginative and varied orchestration serves to underline that.

In summary, I think that Robin Holloway here sheds fresh, understanding light on Brahms’ music. I liked and admired what I heard and I also liked the sympathetic performance of the music by Paul Mann and the BBCSO. I think the dimensions of Brahms’ music and the enhancement which the orchestration provides fully vindicates Holloway’s decision to bestow the title ‘Symphony’ on what he has done. Whether other conductors and orchestras will take this piece up is an open question. In my view, it’s a strong piece which is at least as deserving of a place in the repertoire as Schoenberg’s orchestration of the Piano Quartet.

In some ways, I like Holloway’s version of the Variations on a Theme of Schumann, Op 23 even more, even if the dimensions of the original work are a bit more modest. These Variations for piano duet are, in Holloway’s view, “unjustly neglected”. He suggests that this may be due to the use of the two-piano medium. I wonder also if the work was slow to make its mark because, Holloway reminds us, Clara Schumann and Brahms “suppressed” the piece – and an earlier set of Schumann Variations for solo piano, Op 9 – with the result that neither was published until the late 1930s. In this connection, I have to admit that whilst I’ve heard the Op 9 Variations (review), I don’t believe I’ve ever encountered the Op 23 set in their original form.

I very much enjoyed hearing Robin Holloway’s take on these Variations. Again, his feeling for the Brahms idiom in terms of scoring is much in evidence – though not slavishly so. The way the Theme itself is announced gently by the strings and then taken up by the woodwinds strikes me as being very Brahmsian. A little later, Variation 3 features, in Holloway’s words. “suave sensuous melodic contours” and it seems to me that he clothes this music in a very Brahms-like dress. Even more idiomatic is the scoring of the next variation, which is marked Misterioso. Holloway suggests that Variation 8 is “almost an extra Hungarian Dance”. I know what he means, but his use of woodwinds and horns put me in mind even more of the Serenades. Variation 9 is marked Maestoso. Holloway describes it as a funeral march. For me, the tempo (which sounds right for the music) is fractionally too swift for that. However, the rhythms are definitely martial. To my ears, the music is turbulent and Holloway’s scoring of it is suggestive of some powerful passages in the symphonies which Brahms had yet to write. This martial demeanour is carried over into the final variation and then into the Epilogue, which follows attacca. Here, Holloway tells us, he has extended Brahms’ music “to bring closer to the surface the latent grief [for Robert Schumann] and bitterness that the original eschews”. I’m not in a position to say where Brahms ‘leaves off’ and Holloway begins in this Epilogue. What I will say, though, is that I found the overall result cohesive and convincing.

Brahms’ Op 23 is a fine piece and I very much admire the new light which Robin Holloway has so skilfully and sympathetically shone upon the music.

The remaining piece on this disc is another which I’ve not encountered in its original form – or perhaps I should say ‘original forms’? Schumann wrote his Six Canonic Studies in 1845 for the pedal piano, an instrument which Robin Holloway says was “short-lived”; he believes it was primarily intended for the playing of organ music in a domestic environment. Nearly fifty years later, in 1891, Debussy arranged the music for two pianos; I’ve never heard either version. Robin Holloway says that he has based his orchestration – for chamber orchestra – on Debussy’s arrangement. He also adds that he has “in some places [added] very brief interpolations and endings in the spirit of both composers”. The only such addition that I was in a position to identify – and only because it was specifically referenced in the documentation – was a short interlude between the fifth and sixth Studies; so seamless is the addition that I wouldn’t have been any the wiser had Toccata not made me aware of it.

I have to say that the very title – ‘Six Canonic Studies’ – had made me wonder, prior to listening, if the music might be a bit dry; such is not the case. The Studies are quite brief – the longest plays here for 4:07 – but they are charming and in Holloway’s sympathetic scoring they are very pleasing to hear. The second Study, for instance, is marked Gently lilting, flowing and, to coin a phrase, the music does just what it says on the tin, helped by transparent scoring and a suitably delicate performance. The fourth Study bears the instruction Con moto amabile: supple and airy. What we hear is indeed ‘supple and airy’, not least because Holloway’s woodwind writing is so felicitous. The last Study is Andante serioso: both music and scoring have a warm glow, which makes this miniature into a lovely end to a set of pieces that were a welcome discovery for me.

I’m full of admiration for the work that Robin Holloway has done on these three scores. It would be presumptuous to say he has shed new light onto the music; I don’t think that was ever his intention. Rather, I’d prefer to say that he has shed additional life onto these scores. His orchestrations seem to me to be consistently tasteful and idiomatic. Paul Mann and the BBCSO play the music very well indeed. Engineer Adaq Khan has recorded the performances with skill and sympathy.

This is a disc which is definitely worth hearing, especially by those who, like me, love the music of Johannes Brahms.

Previous review Stephen Barber (August 2023)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site