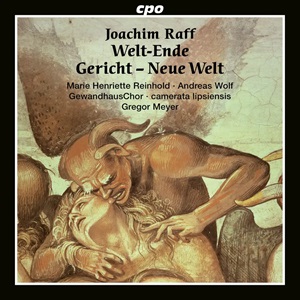

Joachim Raff (1822-82)

Oratorio: Welt-Ende – Gericht – Neue Welt, Op 212 (1882)

Marie Henriette Reinhold, contralto

Andreas Wolf, baritone

Gewandhaus Choir

camerata lipsiensis / Gregor Meyer

rec. 2022, Leipzig Gewandhaus Great Hall

cpo 555 562-2 [2 CDs: 107]

I cannot surely be the only person who ever looks at the back of vocal scores of oratorios and wonders at the extensive listings of totally unknown works by totally unknown composers. They are catalogued at such length by hopeful publishers, evidently seeking to capitalise on the seemingly insatiable appetite of large Victorian choral societies for suitably religious and secular works for inclusion in their concerts. With the gradual decline of these gargantuan bodies of singers during the twentieth century, many of these works, which once engaged the enthusiasm and skills of so many people, almost seemed to vanish into the realm of the dinosaurs. But without even the excuse of cosmic cataclysm to explain their extinction. Only a handful of these oratorios survived the cull. At one time even major works by such established composers as Elgar, Dvořák, Gounod or Sullivan, which had won such accolades at their first performances, seemed to have been consumed wholesale by the mists of time. The recording industry has a thankfully insatiable appetite for novelty and discovery and a very good thing too. It has served to keep such offerings as King Olaf, Saint Ludmila, Mors et Vita or The Golden Legend available for modern audiences to hear and enjoy. These works may have their dull passages (especially when the earnest composer’s appetite for fugal development takes hold), but at their best they can contain sections of scorching genius which thoroughly deserve exhumation. Enthusiastic performances can breathe new life into works which may once have been thought thoroughly beyond the pale. They certainly deserve the occasional outing at least as much as smaller choral works from the same period such as Stainer’s Crucifixion or Maunder’s Olivet to Calvary, both of which (with their less extravagant demands on soloists and chorus) continue to feature in church concerts to this day.

But Raff’s cumbersomely entitled oratorio Welt-Ende – Gericht – Neue Welt (World’s End – Judgement – New World) hardly even entered the periphery of the Victorian oratorio repertory before it fell into oblivion. It was first performed shortly before the composer’s death, and although Sullivan sponsored a performance in Leeds it shortly thereafter suffered the same eclipse as the composer’s once-popular symphonies and ceased to be performed anywhere at all. This recording results from a performance given in 2022 in Raff’s old stamping ground of Leipzig, where nearly all of his triumphant premières during his lifetime had taken place. Even there, it had never been given in concert. It is a good performance, clearly well-rehearsed, even if occasionally lacking in the full measure of fire and engagement which may have gripped the listener more. But the work certainly has its moments of imagination. The depiction of the four horsemen of the Acopalypse is consigned to the orchestra alone in a series of ‘interludes’; the uninspired linking recitative between the movements is pedestrian in the extreme, but the instrumental writing is something else again. Presumably taking his cue from such works as Schubert’s Ninth Symphony, Raff allows himself in each section to experiment almost monothematically with a repeated ostinato phrase, which rises and falls sequentially. It never allows itself to deviate from its driven and headlong progression – in a manner that almost anticipates by a century or more the procedures of modern minimalism. The results might be described as simply repetitive, were they not so fascinatingly devoid of the usual developmental procedures of nineteenth century romanticism; and each of the movements culminates in the same chorale-like brass postlude, which brings a sense of impending doom to the music. The climax of the work comes at the end of the first half, with a stupendous chorus where the rulers of the world call upon the mountains to hide them from the wrath of God; the timpani at the end threaten to break out into soloistic thunder in a manner that recalls Berlioz and anticipates Strauss. Unfortunately, however, Raff is unable to sustain this level of inspiration for the second half, where his depiction of the New Jerusalem is tritely Victorian in the most sentimental manner. Only another orchestral interlude depicting the dead rising to confront Judgement brings another moment of high drama.

The bulk of the musical development is consigned to the chorus, with the roles for the soloists confined to a trio of rather conventional arias, which unfortunately do not even possess melodic charm to counterbalance their sentimental platitudes. But they are well sung. Marie Henriette Reinhold copes well with her predominantly lyrical lines, and Andreas Wolf is particularly impressive in some of his declamatory recitatives setting the narration of Saint John. One suspects that future performances of this oratorio may well find some reason to prune back some of the more repetitive passages of choral writing. But Raff was clearly a master of fugal form and manages to get some good mileage out of the basic procedures. The chorus is not perhaps on the massive scale that would have been expected at its first performances, but their singing is crisp and accurate and the orchestral playing (by a group who appear to have forsworn the use of capital letters) rises to the occasion when Raff gives them their head.

The 40-page booklet by cpo (another body seemingly allergic to capital letters) is as usual a mine of information, and unlike some of the more abstruse essays sometimes furnished by this company the results (in English and German) are both readable and germane. Full texts and translations into English are provided. The cover, a detail from a painting by Luca Signorelli entitled The end of mankind, is a particularly hideous example of religious Renaissance art. The work itself is clearly not a forgotten masterpiece, but it is fascinating and enjoyable in many places and certainly deserves its occasional moments in the sun. We must be grateful to all those involved in the production.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site