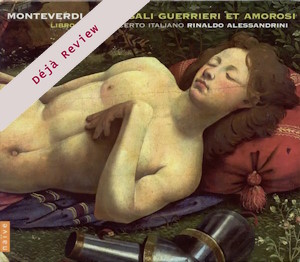

Déjà Review: this review was first published in May 2007 and the recording is still available.

Claudio Monteverdi (1567-1643)

Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi: libro ottavo (1638)

Concerto Italiano/Rinasso Alessandrini

rec. 1997-2005, Centro Giovanni XXIII, Frascati; Salone della Musica, Villa Medici, Ora Giulini, Briosco; Palazzo Farnese, Rome, Italy.

Naïve OP30435 [3 CDs: 180]

Monteverdi’s eighth book of madrigals was published in Venice in 1638, under the title of Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi (Madrigals of Love and War), some nineteen years after the publication of his seventh book of madrigals (also in Venice). Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi actually incorporates some work (such as the ‘Ballo delle ingrate’) actually predated, by some distance, even that seventh book; some of the works included belonged to the 1620s; some was written nearer to the date of publication. Taken as a whole, this was certainly the most substantial and complex collection published by Monteverdi and, since it contains some of his very best work, it follows that this 1638 volume is one of the high points of European vocal music.

There is masterpiece after masterpiece in this great collection and through the skilful use of varied resources which characterises Monteverdi’s work here, the sheer precision and sensitive strength of Monteverdi’s writing, the human passions (War and Love are, essentially, a pair of complementary opposites – antithetical states of the human soul and of human activity, which turn out, as experienced, to have more than a little in common) find glorious and moving expression with remarkable power. The nature of Monteverdi’s ambitions – and some sense of how radical they were – is made very clear in the Preface which he contributed to the volume. In it Monteverdi relates his musical practice to his belief that the human mind “has three principal passions or affections: that is, anger, temperance and supplication (or humility)”, observing that “the intrinsic nature of our voices falls into high, low and medium registers” and affirming that musical theory describes three corresponding styles by the terms “concitato [agitated], … temperato [temperate] and molle [soft/languid]. All three are to be heard in the Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi. AsMonteverdi himself points out, he had few working models of the ‘agitated’ style and this was his greatest innovation – not least as it was employed in some parts of ‘Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda’. Overall we might say that the defining feature of Monteverdi’s work here was to find ways of putting all the resources of music, instrumental and vocal, at the service of text, of meaning and mood as enshrined in the verbal text, without ever robbing music of its own nature or dignity. The results might, in a sense, be thought of as bringing about the end of the madrigal by stretching and fulfilling its conventions and possibilities so absolutely that serious composers could no longer return to the ‘conventions’ of the form as they had previously been established. As Rinaldo Alessandrini puts in his booklet notes – “In the eighth book, Monteverdi demolishes the form of the classical madrigal, setting himself the task of reinventing it each time according to the demands and potential of a poetic text”. And how well he does it!

What we have on this three CD set is a thoroughly rewarding interpretation of Madrigali guerrieri et amorosi under the direction of Alessandrini, working with his Concerto Italiano – or, to be more precise, with two (three?) slightly different incarnations of the Concerto Italiano. The first two CDs were recorded in the 1990s and have been issued previously. The third CD is, I believe issued here for the first time, and was recorded less than eighteen months ago.

The two most explicitly dramatic, or at least quasi-dramatic pieces – and the longest – are both presented on Disc 1. Both ‘Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda’and the ‘Ballo delle ingrate’ were printed with what are effectively stage directions. The score of the ‘Ballo’ is prefaced by the following instructions:

“A set must be constructed showing the mouth of Hades with four openings on either side, belching forth fire, and from which the Ingrate Souls emerge two by two with mournful gestures to the sound of the entrance music which marks the start of the ballet, and which may be repeated until all have reached their respective positions in the centre of the stage ready for the ballet to begin. Pluto stands in the centre, leading them with slow, solemn steps. The entrata over, he stands aside for a time; the dance begins, but is interrupted by Pluto, who addresses the Princess and the other Ladies present as indicated. The Ingrate Souls should wear ash-grey costumes adorned with artificial teardrops. The ballet over, they return to Hades in the same way as they entered, and to the same mournful music; one of them remains behind on stage to sing the lament as written before she too returns to Hades”.

With a text by the significant poet Ottavio Rinuccini, words, music, movement, costume, scenery – and, no doubt, other elements too – have taken us well beyond the concept of the ‘madrigal’ as normally understood. The two pieces on this first disc get particularly impressive performances. They – perhaps especially the ‘Combattimento’ – are especially well suited to Alessandrini’s approach, with his fondness for startling contrasts of tempo and dynamics, his encouragement of his singers to characterise in a way that can, at times, come near the boundaries of caricature. Roberto Abbondanza’s bass voice as the narrator in the ‘Combattimento’ is a thing of beauty and conviction, his understanding of the stile concitato everywhere apparent. As Clorinda, Elisa Franzatti sings with exquisite tenderness in her dying words to Tancredi, persuasively interpreted by Gianluca Ferrarini. In the ‘Ballo’ another bass, Daniele Carnovich is an imperious Pluto, singing with both immense gravity and considerable grace.. Cupid (Francesca Russo Ermolli) and Venus (Rosa Dominguez) blend their voices magically.

In the second and third CDs Alessandrini and his company give us the shorter pieces, some of them rather closer to our traditional understanding of the madrigal, though the use of instrumental accompaniment, used as part of Monteverdi’s subtle understanding of his chosen texts – texts by poets such as Marino, Petrarch, Guarini, Rinuccini and Fulvio Testi – makes for music which is never easily or obviously limited by generic definitions. There are many minor masterpieces (minor in length, at least) here. The setting of Petrarch’s sonnet ‘Hor che’l ciel e terra e ’l vento tace’ is quite stunning, beginning, in the octave, with a hushed evocation of silence and the night sky, an evocation musically troubled by the unhappy speaker’s pains of love even before the text makes them explicit, and closing, in the setting of the sestet, in music which evokes the text’s despair while retaining great dignity. The rhythmic control of this performance, and the perfection with which voices are blended, are exemplary. Rossana Bertini is a seductively poignant soloist in the famous ‘Lamento della Ninfa’ – but it would be pointless to go on listing the many pleasures of this set. I suspect that I should end by listing every track.

In an interview printed in issue 17 of Goldberg, Alessandrini summed up his view of Monteverdi (and especially his madrigals) very succinctly:

“ Monteverdi was the father of a revolution in Western music. He was at a crossroads between vocal music, instrumental music and opera, and invented a new, far-reaching style. He made huge strides, for example, in the Eighth Book of Madrigals, particularly in Il Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda. There is no word to define this work; it isn’t a madrigal or an opera”.

That is the vision that underlies these recordings, and it makes for powerful, beautiful and moving listening. There are other complete recordings of Monteverdi’s Eight Book of Madrigals and – of course – there have been many recordings of individual items from the book. Here and there – especially on the first two CDs – there are very slight blemishes of instrumental intonation in Alessandrini’s performances. But overall this is a splendid set, a recording which does something like justice to one of the great vocal collections. These are very ‘Italian’ performances – full of drama, full of intensity, not afraid of exaggeration, never hampered by reticence. Some listeners will, perhaps, find them just a little too much so. Not me. This is the best complete set I know. Alessandrini and his company show one just how fully Monteverdi’s work speaks of the aesthetic world of its time, in a language that we can hear and understood. Alessandrini finds in the music (and texts) the equivalent of that theatricality of gesture and posture which characterises the paintings of Monteverdi’s contemporaries such as, say, Guido Reni and Guercino, a theatricality which is thoroughly ‘physical’ and yet simultaneously registers the movements of the heart and spirit. So does Monteverdi’s music. Look at Reni’s Angel Musicians in the frescoes of the Palazzo del Quirinale in Rome and it’s hard not to feel that they must be playing and singing Monteverdi! And if we could hear them they would surely sound something like the music we hear on these three discs!

Glyn Pursglove

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free

Contents

1. Combattimento di Tancredi e Clorinda [22:03]

2. Il Ballo delle ingrate [36:10]

3. Sinfonia a doi violini e una viola di brazzo [0:45]

4. Altri canti d’amor, tenero arciero, a sei voci con quattro viole e doi violini [9:52]

5. Lamento de la Ninfa [4:43]

6. Vago augelletto, che cantando vai, a sei e sette voci con doi violini e un contrabasso [5:42]

7. Perchè t’ en fuggi, o fillide? A tre (alto, tenore e basso) [5:59]

8. Altri canti di marte, a sei voci et doi violini [8:59]

9. Ogni amante è guerrier [14:18]

10. Hor che ’l ciel e la terra e ’l vento tace, a sei voci con doi violini [10:46]

11. Gira il nemico, insidioso amore [5:43]

12. Dolcissimo uscignolo, a cinque voci, cantato a voce piena, alla francese [3:42]

13. Ardo, ardo, avvampo, mi struggo, a otto voci con doi violini [4:16]

14. Introduzione e ballo [9:40]

15. Se vittoria sì belle, a doi tenori [2:39]

16. Su, su, su, pastorelli vezzosi, a tre, doi canti e alto [2:33]

17. Ardo e scoprir, ahi lasso, io non ardisco, a doi tenori [3:30]

18. Chi vol aver felice e lieto il core, a cinque voci, cantato a voce piena, alla francese [2:06]

19. Armato il cor d’adamantina fede, a doi tenore [2:20]

20. Non partir ritrosetta, a tre, doi alti e basso [4:17]

21. O sia tranquillo il mare, a doi tenori [4:20]

22. Mentre vaga angiolwtta, a doi tenori [9:31]

23. Ninfa che, scalza il piede [5:19]