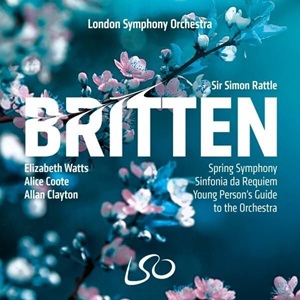

Benjamin Britten (1913-1976)

Sinfonia da Requiem, Op 20 (1940)

Spring Symphony, Op 44 (1948-49)

The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra: Variations and Fugue on a Theme of Purcell, Op 34 (1945)

Elizabeth Watts (soprano); Alice Coote (mezzo-soprano); Allan Clayton (tenor)

Tiffin Boys’ Choir; Tiffin Children’s Chorus; Tiffin Girls’ School Choir; London Symphony Chorus

London Symphony Orchestra / Sir Simon Rattle

rec. live, 16 & 18 September, 2018 (Op 44); 7 & 8 May, 2019 (Op 20); 18 May 2021 (Op 34), the Barbican Hall, London

Texts included

LSO Live LSO0830 [79]

This generously-filled Britten compilation dropped through my letterbox just in time for my colleagues and I to listen to it in our most recent session in the MusicWeb Listening Studio. Broadly, we liked what we heard and our admittedly limited sampling of the disc whetted my appetite for concentrated listening to the whole programme.

The recordings derive from three separate sets of concerts in which Sir Simon Rattle conducted the LSO between 2018 and 2021. Rattle recorded quite a number of works by Britten during his long spell with the CBSO and I have most, if not all, of those recordings in my collection, notably his very fine recording of War Requiem (review). He set down versions of both the Sinfonia da Requiem and The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra during his Birmingham years – excellent recordings in both cases. However, to the best of my knowledge he has not subsequently recorded much Britten; furthermore, I believe Spring Symphony is completely new to his discography. So, this new issue is of particular interest.

Whenever I receive a live recording for review, I look to see if the performance in question was reviewed for Seen and Heard. In this instance, only one of the works was covered by a colleague: Chris Sallon attended the concert on 8 May 2019 at which Sinfonia da Requiem was performed along with Mahler’s Fifth Symphony (review). The Britten piece must have made a terrific impact that night in the Barbican; it certainly does here. Rattle and the LSO bring great intensity to the opening ‘Lacrymosa’, even in the pages where the music is apprehensively subdued in volume. I appreciated the amount of detail that comes out in this recording. Rattle builds the movement inexorably to its implacable climax: in the Listening Studio, my colleague Len Mullenger suggested that he would have preferred a slightly faster pace in the build-up to the climax. I take his point, but there is still great urgency in the performance. The ‘Dies irae’ is delivered with snarling precision at the fast and furious pace that Britten demands. The playing is razor-sharp and terrifically controlled; this is a frenetic dance of death. In his very useful notes, Philip Reed describes the ‘Requiem aeternam’ movement as a “consoling lullaby”. I’d take mild issue with the term lullaby; there is indeed a sense of consolation here, but even so there’s intense emotion in the music and that’s brought out in this performance. I admired this account of Sinfonia da Requiem very much.

Next up is Spring Symphony. As Philip Reed reminds us, this score, like Peter Grimes, was commissioned by Serge Koussevitzky. Other commitments prevented Britten from fulfilling the commission for a couple of years and eventually Koussevitzky generously allowed the world premiere to take place in July 1949 at the Holland Festival. Eduard van Beinum conducted the piece with a trio of distinguished soloists: Jo Vincent, Kathleen Ferrier and Peter Pears. (A recording of that premiere was issued 30 years ago by Decca (440 063-2); it’s a good performance – Ferrier is especially memorable – though the sound calls for some tolerance.) Rattle, too, has a fine solo team at his disposal. Britten conceived the tenor role with the voice of Peter Pears specifically in mind. Allan Clayton is a very different type of tenor, but I liked his contributions very much indeed; as an example, his voice has clarity and ring to it in ‘The Merry Cuckoo’, but equally striking is his lightness of touch in that setting. He also impressed me in his witty duet with Elizabeth Watts in ‘Fair and Fair’. The soprano soloist has the least prominent role in the work, but Ms Watts offers consistently excellent singing. Alice Coote has some choice numbers to sing. I like the warmth she brings to ‘Maids of Honour’ and she is, if anything, finer still in ‘Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed’.

In that sensuous Auden setting, Ms Coote benefits from expertly calibrated support from both the LSO and from the London Symphony Chorus. This is the ideal point at which to mention the excellence of the chorus work in this performance. The London Symphony Chorus were prepared by Simon Halsey and their singing displays his scrupulous attention to detail, not least in the matter of dynamics. The dynamic range of the adult choir is absolutely exemplary in the Introduction, ‘Shine out’. Between them, Halsey and Rattle ensure ideal observance of Britten’s precise dynamics and as a result the music makes its full effect. A little later, I admired very much the way the LSC deliver ‘The Morning Star’ and at the end of the work, the adult chorus plays its part to excellent effect in the complex ensemble that is the finale (‘London, to Thee I do Present’). The score includes a crucial role for a children’s chorus, here performed by young singers from no fewer than three Tiffin School choirs. Prepared for this important assignment by James Day, the children do an absolutely marvellous job. I love their perky, almost cheeky, contributions (both sung and whistled) to ‘The Driving Boy’ and in the penultimate number, ‘Sound the Flute’ these young singers are in no way put in the shade by their adult colleagues in the LSC. In the finale, the children’s ‘Sumer is icumen in’ achieves just the right cut-through (tr 15, 5:54). Taking part in this prestigious concert must have been an exciting assignment for these young singers; they acquitted themselves with aplomb in a manner of which Britten would surely have approved.

It seems almost superfluous to say that the London Symphony Orchestra makes a distinguished contribution to this performance. Britten’s orchestration is wonderfully inventive and the LSO brings out all the colour and illustrative detail in an ideal fashion. This is the kind of score in which Simon Rattle’s famed keen ear for detail is a huge asset; he ensures that we hear everything clearly, but he’s just as alive to the big picture of the symphony. I enjoyed both the detail and the sweep in this performance.

The children play an important part in Spring Symphony. Given that, and Britten’s lifelong determination to include youngsters in sophisticated music, it feels very fitting that the disc should end with The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra. Many years ago, I had the opportunity to take part in an orchestral study weekend for amateur players, directed by the late Arthur Butterworth. Spending a good deal of time getting to grips with this score made me appreciate just what a work of genius it is. Britten set out with the intention of guiding children through the instruments of the orchestra – an objective that he met in full. But his real triumph lay in creating an orchestral showpiece that quickly established itself as an independent repertoire piece. As I listened to this vivacious performance, I was reminded that Britten’s genius lay not just in the wit and invention with which he showed off each orchestral instrument in turn, but also in the accompaniment which he devised for each variation. The LSO plays the work with the virtuosity and flair that one would expect from this ensemble. Rattle gives his orchestra their head, both individually and collectively, and the result is a sparkling performance. LSO Live have tracked the recording very intelligently; there are five separate tracks for each ‘family’ of variations, as well as individual tracks for the Theme and for the concluding fugue.

I listened to the stereo layer of this hybrid SACD and I thought the recordings were very successful. As we commented in our Listening Studio Report, referenced above, the Barbican Hall’s acoustic can be tricky; sometimes, a recording made there can sound too dry or too close – or both. On this occasion, the acoustic seems right for the music, especially the two purely orchestral scores, and the engineers have produced very good results. The documentation is excellent: the notes by Philip Reed and Helen Wallace are good guides to the music, and all the texts for Spring Symphony are included.

This is a successful and enjoyable Britten anthology.

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI and helps us keep free access to the site