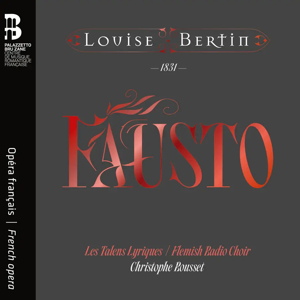

Louise Bertin (1805-1877)

Fausto (1830-1831)

Karine Deshayes – Fausto (mezzo)

Karina Gauvin – Margarita (soprano)

Ante Jerkunica – Mefistofele (bass)

Nico Darmanin – Valentino (tenor)

Marie Gautrot – Catarina (mezzo)

Diana Axentii – Una Strega/ Marta (soprano)

Thibault de Damas – Wagner/ Un Banditore (bass-baritone)

Flemish Radio Choir, Les Talens Lyriques/Christophe Rousset

rec. 2023, La Seine Musicale, Paris, France

Articles, synopsis and full libretto with texts in Italian, French and English in book

Bru Zane BZ1054 [2 CDs: 125]

Bru Zane have once again fastened their beady gaze on a genuine operatic rarity: the very first performance of a work nearly two hundred years old in the form in which it was originally written. The title role in Fausto, based on Part One of the Goethe play, was designated to be sung by a soprano (although the reason is far from clear, there could perhaps have been rivalry with Bellini’s treatment of Romeo in his earlier Capuleti). It was then transformed into a mezzo trouser role before settling in a more conventional manner on the shoulders of a tenor. That was the form adopted at the first staged performances in Paris in 1831. It appears to have been the very first attempt to undertake a musical setting of Goethe’s poem (Part Two did not even appear until the following year) although it was, of course, very far from being the last. The performances appear to have been under-rehearsed and fallible. Despite some favourable critical reception, the opera never reappeared on the stage. Its fate was probably irretrievably sealed when in the following autumn another opera appeared in Paris founded in the fashionable fascination with the devil and all his works. Meyerbeer’s Robert le Diable launched the meteoric rise of both its composer and full-blown French Grand Opèra.

But then there were other reasons why Bertin’s Fausto failed to establish itself. She was not only a woman (writing for a theatre which had never staged another work by a member of her sex) but crippled from infantile polio. That clearly would have limited her physical ability to take any meaningful part in the preparations for her opera on stage. She had influential connections – her father was one of the major music critics in Paris, and she was close friends with Berlioz who later dedicated his song cycle Les nuits d’été to her. But although those may have eased her passage onto the stage, they could do little to establish her long-term reputation, and her music subsequently disappeared from sight entirely. We are informed that when Bru Zane initially expressed interest in mounting a revival of the work some ten years ago, even the full score itself had disappeared. But it has now emerged from the recesses of the French National Bibliotèque. The enterprising company has prepared a new edition, reverting to the composer’s original designation of the hero as a soprano. They deliver the music in one of their admirable presentations complete with extensive notes and essays contained in a hard-back book of some 200 pages. The score is sung in Italian, as at the first performances, but there are full translations into French and English, and we get a large orchestra of period instruments (only double woodwind, but four horns and a full brass contingent).

Was it worth all the trouble? Most certainly it is a very interesting work, fascinating in how it approaches the text and with plenty of idiomatic writing. Bertin certainly appreciated and understood the human voice, and even the re-allocation of the title role from a male to a female singer sounds perfectly natural once you accept the operatic convention. And nowadays, with Bellini’s Romeo in our consciousness, that is more tolerable than it was in the days when Abbado transferred that part to a tenor for his stage performances in the 1960s. It is difficult to imagine a better case for the music being made than in this performance, which is much more than simply a conscientious act of pious resuscitation. But whatever its merits in musical terms, when it comes to consider the opera as a treatment of Goethe, it is dramatically flaccid and frequently falls short. The garden scene is charming, but any sense of menace in the treatment of Mephistopheles is in decidedly short supply. The scene in the cathedral where Marguerite is tormented by the evil spirit, one of the highlights of Gounod’s treatment of the subject, is conventional in its choral writing. And the final trio, where Gounod lifts his opera altogether onto an altogether higher plane, in Bertin’s hands simply fails to bring the drama to its admittedly disingenuous conclusion, even though the final stroke on the gong (shades of Rachmaninov’s Symphonic Dances) is a surprising touch. But then we are inevitably well aware of later and greater treatments of the text, in a manner which means that judgement is inevitably skewed by reminiscences of Berlioz, Schumann, Boito and other composers. If we did not have such exalted standards embedded in our brains, Bertin might not seem to be quite so unsatisfying at those junctures. Indeed, an entirely innocent ear might well find the music at those moments more enthralling.

That would certainly be warranted by the performances here. Even the vapid twitterings of the abandoned Marguerite or the enthusiastically bouncing stratospheric writing for the military Valentine strike fire in the performances by Karina Gauvin and Nico Darmanin. In the final trio, Karine Deshayes makes an impact as Faust, despite disconcertingly heard in the wrong octave. Only Ante Jerkunica as Mephistopheles lacks impact, sounding far too well-behaved for the devil even when in his most suavely insinuating moods. Sometimes, too, the dry recitative which launches scenes (in both the final Acts) really allows the dramatic tension to collapse. The music to accompany the duel and death of Valentine is feebly conventional in the extreme. The string playing, exuberant where it does rise to the occasion, is sometimes slighted by the recording balance; one can imagine more fiery engagement in the hands of a Beecham, for example. But the spick-and-span delivery is gratefully received in its own right, and Christophe Rousset is careful not to allow what dramatic tension there is in the score to drain away.

Bru Zane’s presentation, as I have already observed, is treasurable – a model of what such an issue should be. The essays cover a wide span of information not only about Bertin and her music, but also more generally about opera in Paris during the period after Rossini’s retirement. That provides valuable background to Berlioz’s more familiar misadventures in the following generation. Fausto may not be the rediscovery of a work of a genius – and hardly whets the appetite for a recording of another of Bertin’s scores – but it does have value, not only as an opera in its own right but also as a pioneer in the treatment of Goethe in the years that were to follow.

Paul Corfield Godfrey

Previous review by Mike Parr (March 17, 2024)

Buying this recording via a link below generates revenue for MWI, which helps the site remain free.