Richard Wagner (1813-1883)

Parsifal (1882)

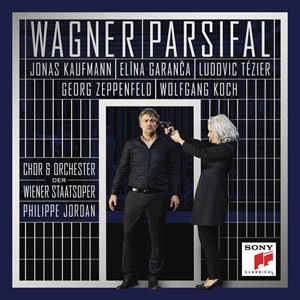

Parsifal, Jonas Kaufmann (tenor); Kundry, Elīna Garanča (mezzo-soprano); Amfortas, Ludovic Tézier (baritone); Gurnemanz, Georg Zeppenfeld (bass); Klingsor, Wolfgang Koch (baritone); Titurel, Stefan Cerny (bass)

Wiener Staatsoper / Philippe Jordan

rec. 2021, Vienna State Opera, Austria.

Sony Classical 19439947742 [4CDs: 242]

Wagner’s last opera is a large work, albeit of a rather subdued nature compared to his more outwardly dramatic Ring Cycle. Many would consider the 1950s and 60s recordings of Hans Knappertsbusch to be the finest recordings of this opera, but this more small-scaled approach may appeal to those who want their Wagner to feel more intimate.

Philippe Jordan is likely the main attraction here and his handling of the score is mostly fine. Though I confess to not hearing anything that made me want to place him over other interpreters of the score and did not find anything like the gravitas present in Knappertsbusch’s 1951 traversal (review) which finds magic in the slowest of tempi. Jordan unfurls the prelude with very fine playing from the orchestra, but it feels ever so slightly generalised. For much of the rest of the opera, there is a pervasive feeling that he might be somewhat hindered in his conception by the quality of his soloists.

The most famous of the primary cast is Jonas Kaufmann and while the core voice is more of a light lyric tenor, he darkens it in a way that some might find more suitable for a role like Parsifal. I don’t find the results of that darkening, an integral part of his technique rather than a specific colour chosen for the role, particularly effective. His voice sounds worn, the vibrato is loose and sometimes wobbly and much of the resonance is swallowed which means the voice never seems to reach out over the orchestra. This leads to a dramatically acted but vocally subdued performance, which I find disappointing when compared to more naturally endowed Parsifal’s such as Jon Vickers or Set Svanholm. He does inflect lines with drama, but the musical demands are a struggle; his technique does not allow for a consistent legato and leads to an inadequate balance with the orchestral sonority, though luckily he is captured well and is not audibly swamped by the orchestral tuttis.

Elīna Garanča too sounds underpowered, though some phrases in the middle of the voice are shaped nicely. The basic tone of the voice is more soprano-ish than mezzo and she lacks the resonance that properly equalised and integrated registers provides. Again, since she has been captured well this is not so much a problem, but it robs the performance of a degree of theatricality. When she leaves the middle of the voice or puts pressure on the instrument, the tone becomes unfocused and wobbly, which prohibits her from being as musically attentive as she could be. While I can enjoy the Kundry of Martha Mödl who does not have the most alluring of vocal timbres, I find Garanča’s wobbles harder to accept as they leave Kundry sounding more like an elderly woman than a seductive temptress.

As seems to be the case with this performance preferring smaller scale vocalism, Georg Zeppenfeld is a lighter and brighter Gurnemanz than some may be used to. He does at least inflect the text well and does not wobble. Of the performances of the main cast, his hinders the performance the least and the voice shows more focus than the others, meaning he can project some of the drama in a more immediate manner.

Unfortunately, Ludovic Tézier is, much like Kaufmann, swallowing his voice and in the process hindering his effectiveness on multiple levels. Surely, singing with a full, penetrating tone, and clear vowels is an essential aspect of unamplified singing, especially in an art form as large-scale as opera. Yet time and again I am finding singers who are attempting to artificially alter the tone of their sound and in the process losing resonance, clarity, and the ability to musically connect the notes and words of their part. Wagner himself preferred singers of the bel canto tradition who sung with a focused, released sound, enabling them to be heard not just clearly but with a visceral immediacy. This allows an ease of phrasing and vocal inflection which is all but lost when you resort to a technique which works against the body rather than with it. Stefan Cerny’s aged Titurel is, maybe appropriately, unsteady and while I have fewer major reservations about Wolfgang Koch’s Klingsor this is far from enough to salvage the performance. As for the supporting cast, they range from acceptable to poor, the flower maidens sounding particularly unsteady and unseductive, possibly more suited to the witches scenes in Verdi’s Macbeth than Klingsor’s magic garden.

Parsifal may not immediately seem to be an opera which requires great voices, and maybe it doesn’t, but it cannot make the desired effect with poor vocalism. I felt rather underwhelmed by the cumulative effect, and the many moments of vocal distress are unpleasant and untheatrical. It’s a shame that I can’t comment more upon the level of interpretation, but much of this seems lost or at least highly disrupted by the lack of strong, steady, and easy vocalism amongst the principal artists. Of course this is a very nice sounding recording and the orchestral details are well-captured, so for those with an interest in hearing a performance in up-to-date sonics, I can see the appeal of having this. It is also very nicely packaged with a full libretto, photos, and writings. As a performance, both as music and as drama, this falls at the first or, for those who find the orchestral writing primary, the second hurdle.

If you are not so concerned with state-of-the-art sonics then the prime recommendation as far as I see it is the Knappertsbusch performance of 1962 (review) which fields an excellent cast of soloists as well as good, atmospheric, stereo sound. In very acceptable mono, and well remastered by Pristine, his 1951 performance is slower and finds even more of that special atmosphere that makes this opera unique. Martha Mödl and Wolfgang Windgassen find more nuance and drama in their roles than their later counterparts, even if their voices aren’t as luxurious. Other accounts worth looking into are Krauss’s 1953 performance (review) and an interesting but unfortunately dim-sounding performance under André Cluytens from La Scala, 1960.

Morgan Burroughs

Help us financially by purchasing from

Other cast

Gralsritter I – Carlos Osuna

Gralsritter II – Erik van Heyningen

Knappe I – Patricia Nolz

Knappe II – Stephanie Maitland

Knappe III – Daniel Jenz

Knappe IV – Angelo Pollak

Blumenmädchen I – Ileana Tonca

Blumenmädchen II – Anna Nekhames

Blumenmädchen III – Aurora Marthens

Blumenmädchen IV – Slávka Zámečníková

Blumenmädchen V – Joanna Kędzior

Blumenmädchen VI – Isabel Signoret

Eine Stimme aus der Höhe – Elīna Garanča